Using A Razor To Whittle Your Choices

Let’s say that you’re trying to decide what causes what and keep getting stuck between multiple alternatives. (This is a process known as Inference to the Best Explanation). You’ve put away your cognitive biases and built arguments that are sound and valid. Your friends give you a lot of advice. But you just can’t decide.

Logical razors can help you out of the jam. A razor helps you eliminate choices, which is often as important as creating options in the first place. A razor says, “It’s not likely to be this one ….” By eliminating options, you make your decision easier. You’re more likely to find the best explanation.

Razors don’t use airtight logic so they’re not foolproof. They could conceivably point you away from a solution that actually works. In general, however, they give you a process for working through ideas and eliminating the least probable ones. Here are my favorite razors.

Occam’s razor – among competing explanations, the one that makes the fewest assumptions is most likely to be right. This was the original razor and comes from William of Ockham, a Franciscan friar who lived in the late 13th and early 14th centuries.

Hitchen’s razor – that which can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence. We should, of course, ask for evidence to back up a hypothesis. If no evidence exists, we can safely dismiss it.

Hanlon’s razor – never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity. If someone injures you, don’t assume that they did so with malicious intent. It’s more likely that they’re just stupid.

Hume’s razor – if a presumed cause is not sufficient to create an observed effect, we must either eliminate the cause from consideration or show what needs to be added to create the effect.

Adler’s razor – a question that can’t be settled by experimentation is not worth debating.

Logical razors help you scrape away explanations that are possible but not probable. They can help you think more clearly. But they don’t always lead you to a conclusion. At some point, you may have to make Pascal’s Wager.

That’s Irrelevant!

In her book, Critical Thinking: An Appeal To Reason, Peg Tittle has an interesting and useful way of organizing 15 logical fallacies. Simply put, they’re all irrelevant to the assessment of whether an argument is true or not. Using Tittle’s guidelines, we can quickly sort out what we need to pay attention to and what we can safely ignore.

In her book, Critical Thinking: An Appeal To Reason, Peg Tittle has an interesting and useful way of organizing 15 logical fallacies. Simply put, they’re all irrelevant to the assessment of whether an argument is true or not. Using Tittle’s guidelines, we can quickly sort out what we need to pay attention to and what we can safely ignore.

Though these fallacies are irrelevant to truth, they are very relevant to persuasion. Critical thinking is about discovering the truth; it’s about the present and the past. Persuasion is about the future, where truth has yet to be established. Critical thinking helps us decide what we can be certain of. Persuasion helps us make good choices when we’re uncertain. Critical thinking is about truth; persuasion is about choice. What’s poison to one is often catnip to the other.

With that thought in mind, let’s take a look at Tittle’s 15 irrelevant fallacies. If someone tosses one of these at you in a debate, your response is simple: “That’s irrelevant.”

- Ad hominem: character– the person who created the argument is evil; therefore the argument is unacceptable. (Or the reverse).

- Ad hominem: tu quoque– the person making the argument doesn’t practice what she preaches. You say, it’s wrong to hunt but you eat meat.

- Ad hominem: poisoning the well— the person making the argument has something to gain. He’s not disinterested. Before you listen to my opponent, I would like to remind you that he stands to profit handsomely if you approve this proposal.

- Genetic fallacy– considering the origin, not the argument. The idea came to you in a dream. That’s not acceptable.

- Inappropriate standard: authority– An authority may claim to be an expert but experts are biased in predictable ways.

- Inappropriate standard: tradition – we accept something because we have traditionally accepted it. But traditions are often fabricated.

- Inappropriate standard: common practice – just because everybody’s doing it doesn’t make it true. Appeals to inertia and status quo.Example: most people peel bananas from the “wrong” end.

- Inappropriate standard: moderation/extreme – claims that an argument is true (or false) because it is too extreme (or too moderate). AKA the Fallacy of the Golden Mean.

- Appeal to popularity: bandwagon effect– just because an idea is popular doesn’t make it true. Often found in ads.

- Appeal to popularity: elites – only a few can make the grade or be admitted. Many are called; few are chosen.

- Two wrongs –our competitors have cheated, therefore, it’s acceptable for us to cheat.

- Going off topic: straw man or paper tiger– misrepresenting the other side. Responding to an argument that is not the argument presented.

- Going off topic: red herring – a false scent that leads the argument astray. Person 1: We shouldn’t do that. Person 2: If we don’t do it, someone else will.

- Going off topic: non sequitir – making a statement that doesn’t follow logically from its antecedents. Person 1: We should feed the poor. Person 2: You’re a communist.

- Appeals to emotion– incorporating emotions to assess truth rather than using logic. You say we should kill millions of chickens to stop the avian flu. That’s disgusting.

Chances are that you’ve used some of these fallacies in a debate or argument. Indeed, you may have convinced someone to choose X rather than Y using them. Though these fallacies may be persuasive, it’s useful to remember that they have nothing to do with truth.

Knowledge Neglect — Scots In Saris

If I ask you about the crime rate in your neighborhood, you probably won’t have a clear and precise answer. Instead, you’ll make a guess. What’s the guess based on? Mainly on your memory:

- If you can easily remember a violent crime, you’ll guess that the crime rate is high.

- If you can’t easily remember such a crime, you’ll guess a much lower rate.

Our estimates, then, are not based on reality but on memory, which of course is often faulty. This is the availability bias. Our probability estimates are biased toward what is readily available to memory.

The broader concept is processing fluency– the ease with which information is processed. In general, people are more likely to judge a statement to be true if it’s easy to process. This is the illusory truth effect– we judge truth based on ease-of-processing rather than objective reality.

It follows that we can manipulate judgment by manipulating processing fluency. Highly fluent information (low cognitive cost) is more likely to be judged true.

We can manipulate processing fluency simply by changing fonts. Information presented in easy-to-read fonts is more likely to be judged true than is information presented in more challenging fonts. (We might surmise that the new Sans Forgetica font has an important effect on processing fluency).

We can also manipulate processing fluency by repeating information. If we’ve seen or heard the information before, it’s easier to process and more likely to be judged true. This is especially the case when we have no prior knowledge about the information.

But what if we do have prior knowledge? Will we search our memory banks to find it? Or will we evaluate truthfulness based on processing fluency? Does knowledge trump fluency or does fluency trump knowledge?

Knowledge-trumps-fluency is known as the Knowledge-Conditional Model. The opposite is the Fluency-Conditional Model. Until recently, many researchers assumed that people would default to the Knowledge-Conditional Model. If we knew something about the information presented, we would retrieve that knowledge and use it to judge the information’s truthfulness. We wouldn’t judge truthfulness based on fluency unless we had no prior knowledge about the information.

A 2015 study by Lisa Fazio et. al. starts to flip this assumption on its head. The article’s title summarizes the finding: “Knowledge Does Not Protect Against Illusory Truth”. The authors write that, “An abundance of empirical work demonstrates that fluency affects judgments of new information, but how does fluency influence the evaluation of information already stored in memory?”

The findings – based on two experiments with 40 students from Duke University – suggest that fluency trumps knowledge. Quoting from the study:

“Reading a statement like ‘A sari is the name of the short pleated skirt worn by Scots’ increased participants later belief that it was true, even if they could correctly answer the question, ‘What is the name of the short pleated skirt worn by Scots?’” (Emphasis added).

The researchers found similar examples of knowledge neglect– “the failure to appropriately apply stored knowledge” — throughout the study. In other words, just because we know something doesn’t mean that we use our knowledge effectively.

Note that knowledge neglect is similar to the many other cognitive biases that influence our judgment. It’s easy (“cognitively inexpensive”) and often leads us to the correct answer. Just like other biases, however, it can also lead us astray. When it does, we are predictably irrational.

Ideas and Free Throws

Assume, for a moment, that I’m your manager. I call you into my office one day and say, “You’re doing pretty good work … but you’re going to have to get better at shooting free throws on the basketball court. If you want a promotion this year, you’ll need to make at least 75% of your free throws.”

What would you do? Assuming that you don’t resign on the spot, you would probably get a basketball, go to the free throw line, and start practicing free throws (also known as foul shots). Like most skills, you would probably find that your accuracy improves with practice. You might also hire a coach or watch some training videos, but the bottom line is practice, practice, practice.

Now, let’s change the scenario. I call you into my office and say, “You’re doing pretty good work … but you’re going to have to get better at creating ideas. If you want a promotion this year, you’ll need to increased the number of good ideas you generate by at least 75%.”

Now what? Well … I’d suggest that you start practicing the art of creating good ideas. In fact, I’d suggest that it’s not very different from practicing the art of shooting free throws.

But shooting free throws and creating ideas seem to be very different processes. Here’s how they feel:

- Shooting free throws – you get a basketball, you walk to the line – 15 feet from the basket – and you launch the ball into the air. You’re conscious of every action. You recognize that you’re the cause and a flying basketball is the result.

- Creating ideas – nothing happens … then, while you’re walking down the street, minding your own business – poof! – a good idea pops into mind. You have no sense of agency. Instead of feeling like the cause, you feel like the effect.

The two activities seem very different but, actually, they’re not. In both cases, you’re doing the work. With free throws, you readily recognize what you’re doing. With ideas, you don’t. Free throws happen in your conscious mind, also known as System 2. New ideas, on the other hand, happen below the level of consciousness, in System 1. When System 1 works up an idea, it pops it into System 2 and you become aware of it.

We understand how to practice something in System 2 – we’re aware of our activity. But how do we practice in System 1? How can we practice something that we’re not aware of?

We think of our mind as controlling our body. But, as Amy Cuddy has pointed out, our bodily activities also influence our mental states. If we make ourselves big, we grow more confident. If we smile, our mood brightens.

So how do we use our bodies to teach our brains to have good ideas? First, we need to observe ourselves. What were you doing the last time you had a good idea? I’ve noticed that most of my good ideas pop into my head when I’m out for a walk. When I’m stuck on a difficult problem, I recognize that I need a good idea. I quit what I’m doing and go for a walk. Oftentimes, it works – my System 1 generates an idea and pops it into System 2.

In my critical thinking classes, I ask my students to raise their hands if they have ever in their lives had a good idea. All hands go up. Everybody has the ability to create good ideas. The question is practice.

Then I ask my students what they were doing the last time they had a good idea. The list includes: out for a walk, driving, riding in a car, bus, or train (but not an airplane), taking a shower, drifting off to sleep, and bicycling.

I also ask them what activities don’t generate good ideas. The list includes: when they’re stressed, highly focused, multitasking, overly tired, overly busy, or sitting in meetings.

So how do we practice the art of having good ideas? By doing more of those activities that generate good ideas (and fewer of those that don’t). The most productive activities – like walking – seem to occupy part of our attention while leaving much of our brainpower free to wander somewhat aimlessly. Our bodily activity influences and stimulates our System 1. The result is often a good idea.

Is that perfectly clear? Good. I’m going for a walk.

FOMO/JOMO. Be Here Now.

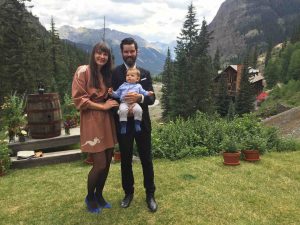

Julia and Elliot recently went to a wedding in Eureka, Colorado, a ghost town situated high in the San Juan Mountains. To say that Eureka is isolated is a vast understatement. Here are some things that the town doesn’t have: landlines, television, internet, wi-fi, mobile phone access, cable, newspapers, radio, and paved roads. When you’re there, you’re there.

Just before the wedding ceremony, ushers collected everyone’s cameras and mobile phones. The couple seemed to be saying to their guests: “We’re glad you’re here. We hope you’re with us fully and completely. Don’t fuss with your cameras and phones. Engage with us in a profound experience. Be here now.”

The place and the process reminded me of Daniel Kahneman’s definitions of the experiencing self and the remembering self. We can focus, engage our senses, and fully experience an activity. What we remember, however, is far different from what we experience. We typically remember two things: 1) the peak experience – the high point of the activity; 2) the end state – how things ended up. (For more on memory traps, click here).

The difference between the two selves has many implications. We remember things differently than they actually happened. This calls into question such things as eyewitness testimony and historical accounts. It may also be why we argue with our spouses – we simply remember things differently. It’s another good reason not to argue in the past tense. (For other reasons, click here).

The difference also affects how we plan our activities. We can plan to: 1) enhance the experience; or 2) enhance our memory of the experience. Let’s say you go to your favorite restaurant. If you want to enhance the experience, you should order your favorite dish. You can enjoy the anticipation and the experience itself. However, you won’t create a new memory. It will simply blend in with all the other times you’ve ordered the same dish. If you want a new memory, order something you’ve never had before. It may be great or not – you can’t anticipate – but it will be more memorable.*

FOMO, of course, is the Fear of Missing Out, which seems to be an increasing concern in today’s society. Everything is accessible and we don’t want to miss any of it. Technologies such a mobile phones, video chat, and instant messages democratize our experience. We can share anything with anyone at any time. We won’t miss a thing.

But, of course, we do miss things. In fact, the very act of inserting technologies into our experiences makes us miss some of the experience. We’re fussing with our cameras rather than experiencing the action. We’re checking baseball scores rather than engaging with others. The desire to miss nothing causes us to miss something: the intensity of the present moment.

FOMO shifts our attention from the experiencing self to the remembering self. We take pictures, which helps us remember and share an experience. But the act of taking pictures insulates us from the experience itself. We’ve inserted technology between our experiences and ourselves.

As you can probably guess, I’m not the first person to suggest that FOMO mania actually causes us to miss much more than we realize. The tech and culture blogger, Anil Dash, coined the term JOMO — the Joy Of Missing Out – more than two years ago. Christina Crook wrote a book called The Joy of Missing Out and popularized the idea of Internet fasts. Sarah Wilson points out that FOMO has eradicated traditional boundaries that separated public time from private time. It used to be easy to spend a quiet evening at home. Now we need to declare an Internet fast to get some alone time.

Though it’s not a new idea, I suspect that the JOMO message needs some more evangelists. As a famous American once said: Be Here Now.

*I adopted the restaurant example from an episode of the Hidden Brain podcast called Hungry, Hungry Hippocampus.