FOMO/JOMO. Be Here Now.

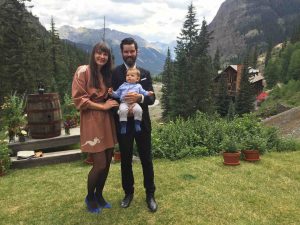

Julia and Elliot recently went to a wedding in Eureka, Colorado, a ghost town situated high in the San Juan Mountains. To say that Eureka is isolated is a vast understatement. Here are some things that the town doesn’t have: landlines, television, internet, wi-fi, mobile phone access, cable, newspapers, radio, and paved roads. When you’re there, you’re there.

Just before the wedding ceremony, ushers collected everyone’s cameras and mobile phones. The couple seemed to be saying to their guests: “We’re glad you’re here. We hope you’re with us fully and completely. Don’t fuss with your cameras and phones. Engage with us in a profound experience. Be here now.”

The place and the process reminded me of Daniel Kahneman’s definitions of the experiencing self and the remembering self. We can focus, engage our senses, and fully experience an activity. What we remember, however, is far different from what we experience. We typically remember two things: 1) the peak experience – the high point of the activity; 2) the end state – how things ended up. (For more on memory traps, click here).

The difference between the two selves has many implications. We remember things differently than they actually happened. This calls into question such things as eyewitness testimony and historical accounts. It may also be why we argue with our spouses – we simply remember things differently. It’s another good reason not to argue in the past tense. (For other reasons, click here).

The difference also affects how we plan our activities. We can plan to: 1) enhance the experience; or 2) enhance our memory of the experience. Let’s say you go to your favorite restaurant. If you want to enhance the experience, you should order your favorite dish. You can enjoy the anticipation and the experience itself. However, you won’t create a new memory. It will simply blend in with all the other times you’ve ordered the same dish. If you want a new memory, order something you’ve never had before. It may be great or not – you can’t anticipate – but it will be more memorable.*

FOMO, of course, is the Fear of Missing Out, which seems to be an increasing concern in today’s society. Everything is accessible and we don’t want to miss any of it. Technologies such a mobile phones, video chat, and instant messages democratize our experience. We can share anything with anyone at any time. We won’t miss a thing.

But, of course, we do miss things. In fact, the very act of inserting technologies into our experiences makes us miss some of the experience. We’re fussing with our cameras rather than experiencing the action. We’re checking baseball scores rather than engaging with others. The desire to miss nothing causes us to miss something: the intensity of the present moment.

FOMO shifts our attention from the experiencing self to the remembering self. We take pictures, which helps us remember and share an experience. But the act of taking pictures insulates us from the experience itself. We’ve inserted technology between our experiences and ourselves.

As you can probably guess, I’m not the first person to suggest that FOMO mania actually causes us to miss much more than we realize. The tech and culture blogger, Anil Dash, coined the term JOMO — the Joy Of Missing Out – more than two years ago. Christina Crook wrote a book called The Joy of Missing Out and popularized the idea of Internet fasts. Sarah Wilson points out that FOMO has eradicated traditional boundaries that separated public time from private time. It used to be easy to spend a quiet evening at home. Now we need to declare an Internet fast to get some alone time.

Though it’s not a new idea, I suspect that the JOMO message needs some more evangelists. As a famous American once said: Be Here Now.

*I adopted the restaurant example from an episode of the Hidden Brain podcast called Hungry, Hungry Hippocampus.