Making Friends in Nine Minutes

What if we could make friends more quickly and more predictably? Would we make more friends? Would life be better? Would we be happier? Would we take fewer tranquilizers?

What if we could make friends in nine minutes?

We usually think of making friends as a pleasurable process. We don’t usually think of it as a necessary process. We could, I suppose, survive reasonably well without making friends. But what if you have to make friends? How would you do it?

This is a problem that faces some social science researchers. If you want to study relationships – how they form, how they influence behavior, etc. – you need to be able to create relationships and measure their degree of closeness.

For instance, you might want to study the effect of friendship on, say, pro-social behavior. Do people in friendly relationships do more good works or fewer? You invite pairs of friends to participate. Assume that you want to compare pairs of people who have been friends for less than six months. You could sort through pairs of people to find those who fit your criteria. But it’s complicated and imprecise.

Alternatively, you could recruit strangers, pair them up randomly, and induce friendships among them. What’s the advantage? Constantine Sedikides and his colleagues wrote about this in their paper, “The Relationship Closeness Induction Task.” They note that “Because newly formed laboratory relationships lack a history of … past interactions, … the researcher is able to examine the effect of relationship closeness per se on the dependent measurements….” Random assignment also reduces the impact of pesky intervening variables.

The methodological advantage seems clear. But … how do you induce a friendship? Sedikides et. al. describe several methods that didn’t seem to work very well. They then propose the Relationship Closeness Induction Task (RCIT) which is built on “… the principle that a vital feature in the development of a close relationship is reciprocal and escalating self-disclosure.” In simpler terms, by sharing information about yourself (self-disclosing) with a stranger who also shares information, you develop a closer relationship.

The RCIT consists of three lists of questions – 29 questions total — and participants are asked to spend nine minutes “mutually self-disclosing”. They spend one minute on List 1, three minutes on list II, and five minutes on List III. The authors note that the RCIT has proved its validity in four different ways:

- Participants reported a higher level of relationship closeness than did control groups, with no gender differences found.

- RCIT induced closeness created statistically significant impacts on dependent variables in several different studies.

- Participants reported that they had adequate privacy and felt comfortable with the process.

- In the allotted nine minutes, participants answered 90% of the questions.

The original questions were written for college students; they’re the most likely participants in these kinds of studies. With just a bit of imagination, however, you could pull out the college-related questions and substitute other, more relevant questions in your friendship induction process.

I suspect by now that you would like to know the 29 questions. Here they are. Now go out and make some friends. You’ve got nine minutes.

List I – One minute

- What is your name?

- How old are you?

- Where are you from?

- What year are you in at University X?

- What do you think you might major in? Why?

- What made you come to the University of X?

- What’s your favorite class at the University of X? Why?

List II – Three minutes

- What are your hobbies?

- What would you like to do after graduation from the University of X?

- What would be the perfect lifestyle for you?

- What is something you have always wanted to do but probably never will be able to do?

- If you could travel anywhere in the world, where would you go and why?

- What is one strange thing that has happened to you since you have been at the University of X?

- What is one embarrassing thing that has happened to you since arriving at the University of X?

- What is one thing happening in your life that makes you stressed out?

- If you could change anything that happened to you in high school, what would that be?

- If you could change one thing about yourself what would that be?

- Do you miss your family?

- What is one habit you’d like to break?

List III – Five minutes

- If you could have one wish granted, what would that be?

- Is it difficult or easy for you to meet people? Why?

- Describe the last time that you felt lonely.

- What is one emotional experience you’ve had with a close friend?

- What is one of your biggest fears?

- What is your most frightening early memory?

- What is your happiest early childhood memory?

- What is one thing about yourself that most people would consider surprising?

- What is one recent accomplishment that you are proud of?

- Tell me one thing about yourself that most people who already know you don’t know.

Tongue-tied On Valentine’s Day?

Valentine’s cards intrigue me. Suellen and I exchange them every year. Some are sweet. Some are funny. Some are silly. Some are mildly sexy. But really, is there anything new in them? Have we come a long way, baby, or are we just recycling platitudes? And how did people in past centuries address their love, passion, and heartaches? What can we learn from our ancestors?

Valentine’s cards intrigue me. Suellen and I exchange them every year. Some are sweet. Some are funny. Some are silly. Some are mildly sexy. But really, is there anything new in them? Have we come a long way, baby, or are we just recycling platitudes? And how did people in past centuries address their love, passion, and heartaches? What can we learn from our ancestors?

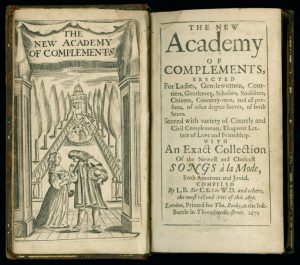

By happy accident, I discovered a partial answer in the Newberry Library in Chicago. The Newberry holds a copy of The New Academy of Complements published in London in the 17th century. The small book – easily tucked in a pocket — is addressed to “both Sexes” and contains a “variety of Courtly and Civil complements” as well as “Eloquent Letters of Love and Friendship … both amorous and jovial.” Happily, the compliments are compiled by “the most refined Wits of the Age.”

What were the best amorous compliments of 17thcentury England? Here are a few of my favorite selections. *

Complemental Expressions towards Men, Leading to The Art of Courtship.

Sir, Your Goodness is as boundless, as my desires to serve you.

Sir, You are so highly generous, that I am altogether senceless.

Sir, You are so noble in all respects that I have learn’d to love, as well as to admire you.

Sir, Your Vertues are so well known, you cannot think I flatter.

Complements towards Ladies, Gentlewomen, Maids, &c.

Madam, When I see you I am in paradice, it is then that my eyes carve me out a feast of Love.

Madam, Your beauty hath so bereav’d me of my fear, that I do account it far more possible to die, than to forget you.

Madam, Since I want merits to equallize your Vertues, I will for ever mourn for my imperfections.

Madam, You are the Queen of Beauties, your vertues give a commanding power to every mortal.

Madam, Had I a hundred hearts I should want room to entertain your love.

I don’t have room to quote many of the gems contained in the book, but here are a few of the categories. Each category provides several models of what to say or write to address the situation. Who knows – you might need one from time to time.

A Gentleman of good Birth, but small Fortune, to a worthy Lady, after she had given a denial.

The Ingratiating Gentleman to his angry Mistriss.

The Lover to his Mistriss, upon his fear of her entertaining a new Servant.

The Jealous Lover to his beloved. The Answer: A Lady to her Jealous Lover.

A crack’t Virgin to her deceitful Friend, who hath forsook her for the love of a Strumpet.

A Lover to his Mistriss, who had lately entertained another Servant to her bosom, and her bed. The Answer: The Lady to her Lover, in defence of her own Innocency.

As you can see, The Academy provides the words to address (and perhaps remedy) most any situation. Is a bald man bothering you? Here’s how to respond:

Sir…while I could be content to keep my Coaches, my Pages, Lackeys, and Maids, I confess I could never endure the society of a bald pate.

I think the Newberry might find an interesting niche market by publishing high quality Valentine’s cards with extracts from The Academy. I know I would buy some. In the meantime, I hope you can find an appropriate quote for whatever your needs are this Valentine’s Day

* The edition held by the Newberry Library was published in 1671. The selections in this article are drawn from the 1669 edition

Ideas and Free Throws

Assume, for a moment, that I’m your manager. I call you into my office one day and say, “You’re doing pretty good work … but you’re going to have to get better at shooting free throws on the basketball court. If you want a promotion this year, you’ll need to make at least 75% of your free throws.”

What would you do? Assuming that you don’t resign on the spot, you would probably get a basketball, go to the free throw line, and start practicing free throws (also known as foul shots). Like most skills, you would probably find that your accuracy improves with practice. You might also hire a coach or watch some training videos, but the bottom line is practice, practice, practice.

Now, let’s change the scenario. I call you into my office and say, “You’re doing pretty good work … but you’re going to have to get better at creating ideas. If you want a promotion this year, you’ll need to increased the number of good ideas you generate by at least 75%.”

Now what? Well … I’d suggest that you start practicing the art of creating good ideas. In fact, I’d suggest that it’s not very different from practicing the art of shooting free throws.

But shooting free throws and creating ideas seem to be very different processes. Here’s how they feel:

- Shooting free throws – you get a basketball, you walk to the line – 15 feet from the basket – and you launch the ball into the air. You’re conscious of every action. You recognize that you’re the cause and a flying basketball is the result.

- Creating ideas – nothing happens … then, while you’re walking down the street, minding your own business – poof! – a good idea pops into mind. You have no sense of agency. Instead of feeling like the cause, you feel like the effect.

The two activities seem very different but, actually, they’re not. In both cases, you’re doing the work. With free throws, you readily recognize what you’re doing. With ideas, you don’t. Free throws happen in your conscious mind, also known as System 2. New ideas, on the other hand, happen below the level of consciousness, in System 1. When System 1 works up an idea, it pops it into System 2 and you become aware of it.

We understand how to practice something in System 2 – we’re aware of our activity. But how do we practice in System 1? How can we practice something that we’re not aware of?

We think of our mind as controlling our body. But, as Amy Cuddy has pointed out, our bodily activities also influence our mental states. If we make ourselves big, we grow more confident. If we smile, our mood brightens.

So how do we use our bodies to teach our brains to have good ideas? First, we need to observe ourselves. What were you doing the last time you had a good idea? I’ve noticed that most of my good ideas pop into my head when I’m out for a walk. When I’m stuck on a difficult problem, I recognize that I need a good idea. I quit what I’m doing and go for a walk. Oftentimes, it works – my System 1 generates an idea and pops it into System 2.

In my critical thinking classes, I ask my students to raise their hands if they have ever in their lives had a good idea. All hands go up. Everybody has the ability to create good ideas. The question is practice.

Then I ask my students what they were doing the last time they had a good idea. The list includes: out for a walk, driving, riding in a car, bus, or train (but not an airplane), taking a shower, drifting off to sleep, and bicycling.

I also ask them what activities don’t generate good ideas. The list includes: when they’re stressed, highly focused, multitasking, overly tired, overly busy, or sitting in meetings.

So how do we practice the art of having good ideas? By doing more of those activities that generate good ideas (and fewer of those that don’t). The most productive activities – like walking – seem to occupy part of our attention while leaving much of our brainpower free to wander somewhat aimlessly. Our bodily activity influences and stimulates our System 1. The result is often a good idea.

Is that perfectly clear? Good. I’m going for a walk.

Why Do Smarter People Live Longer?

A study published last week in the British Medical Journal states simply that, “Childhood intelligence was inversely associated with all major causes of death.”

The study focused on some 65,000 men and women who took the Scottish Mental Survey in 1947 at age 11. Those students are now 79 years old and many of them have passed away. By and large, those who scored lower on the test in 1947 were more likely to have died – from all causes — than those who registered higher scores.

This is certainly not the first study to link intelligence with longevity. (Click here, here, and here, for instance). But it raises again a fundamental question: why would smarter people live longer? There seem to be at least two competing hypotheses:

Hypothesis A: More intelligent people make better decisions about their health care, diet, exercise, etc. and — as a result — live longer.

Hypothesis B: whatever it is that makes people more intelligent also makes them healthier. Researchers, led by Ian Deary, call this hypothesis system integrity. Essentially, the theory suggests that a healthy system generates numerous positive outcomes, including greater intelligence and longer life. The theory derives from a field of study known as cognitive epidemiology, which studies the relationships between intelligence and health.

Hypothesis A focuses on judgment and decision making as causal factors. There’s an intermediate step between intelligence and longevity. Hypothesis B is more direct – the same factor causes both intelligence and longevity. There is no need for an intermediate cause.

The debate is oddly similar to the association between attractiveness and success. Sociologists have long noted that more attractive people also tend to be more successful. Researchers generally assumed that the halo effect caused the association. People judged attractive people to be more capable in other domains and thus provided them more opportunities to succeed. This is similar to our Hypothesis A – the result depends on (other people’s) judgment and there is an intermediate step between cause and effect.

Yet a recent study of Tour de France riders tested the notion that attractiveness and success might have a common cause. Researchers rated the attractiveness of the riders and compared the rankings to race results. They found that more attractive riders finished in higher positions in the race. Clearly, success in the Tour de France does not depend on the halo effect so, perhaps, that which causes the riders to be attractive may also cause them to be better racers.

And what about the relationship between intelligence and longevity? Could the two variables have a single, common cause? Perhaps the best study so far was published in the International Journal Of Epidemiology last year. The researchers looked at various twin registries and compared IQ tests with mortality. The study found a small (but statistically significant) relationship between IQ and longevity. In other words, the smarter twin lived longer. Though the effects are small, the researchers conclude, “The association between intelligence and lifespan is mostly genetic.”

Are they right? I’m not (yet) convinced. Though significant, the statistical relationship is very small with r = 0.12. As noted elsewhere, variance is explained by the square of r. So in this study, IQ explains only 1.44% (0.12 x 0.12 x 100) of the variance in longevity. That seems like weak evidence to conclude that the relationship is “mostly genetic”.

Still, we have some interesting research paths to follow up on. If the theory of system integrity is correct, it could predict a whole host of relationships, not just IQ and longevity. Attractiveness could also be a useful variable to study. Perhaps there’s a social aspect to it as well. Perhaps people who are healthy and intelligent also have a larger social circle (see also Dunbar’s number). Perhaps they’re more altruistic. Perhaps they are more symmetric. Ultimately, we may find that a whole range of variables depend partially – or perhaps mainly – on genetics.

Healing Architecture

I feel better already.

We were in Barcelona last month with our two favorite architects, Julia and Elliot. Of course, we wanted to see the many buildings created by another favorite architect, Antoni Gaudi. A friend also clued us in that, if we wanted to see some really good architecture, we shouldn’t miss the Hospital de Sant Pau.

I enjoy discovering cities but had never thought about visiting hospitals as part of a tourism agenda. Hospitals seem very functional and efficient and somewhat drab. They also look pretty much alike whether you’re in Denver or Paris or Bangkok. They seem to be built for the benefit of the medical staff rather than the patients.

So I was very surprised to find that the Hospital de Sant Pau contained some of the most beautiful buildings I’ve ever seen. The hospital dates to 1401 but the major complex that we visited consisted of about a dozen buildings constructed between 1901 and 1930. The Catalan architect Lluis Doménech I Montaner designed the entire campus, which today claims to be the largest art nouveau site in Europe. The campus is like a fairy tale – every which way you turn reveals something new and stimulating. (My photo above barely does it justice).

(The art nouveau campus was a working hospital until 2009 when it was replaced by a newer hospital – also an architectural gem – just beside it. The art nouveau campus is now a museum and cultural heritage site).

As I wandered about the campus, I thought if I were sick, this is the kind of place I would want to be. It’s beautiful and inspiring. That led me to a different question: Can the architecture of a hospital affect the health of its patients? The answer seems to be: Yes, it can.

The earliest paper I found on healing and architecture was a 1984 study by Roger Ulrich published in Science magazine. The title summarizes the findings nicely: “View Through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery.” Ulrich studied the records of patients who had gall bladder surgery in a Philadelphia hospital between 1972 and 1981.

Ulrich matched patients based on whether they had a view of trees out the window or a view of a brick wall. He studied only those patients who had had surgery between May and October “…because the tress have foliage during those months.” He also matched the pairs based on variables such as age, gender, smoking status, etc. As much as possible, everything was equal except the view.

And the results? Patients “…with the tree view had shorter postoperative hospital stays, had fewer negative evaluative comments from nurses, took fewer moderate and strong analgesic doses, and had slightly lower scores for minor postsurgical complications.”

Ulrich’s study (and others like it) has led to a school of thought called evidence-based design. Amber Bauer, writing in Cancer.Net, notes, “Like its cousin, evidence-based medicine, evidence-based design relies on research and data to create physical spaces that will help achieve the best possible outcome.”

Bauer cites Dr. Ellen Fisher, the Dean of the New York School of Interior Design, “An environment designed using the principles of evidence-based design can improve the patient experience and enable patients to heal faster, and better.” Among other things, Dr. Fisher suggests, “A view to the outdoors and nature is very important to healing.” It’s Ulrich redux.

I’ll write more about evidence-based design and the impact of architecture on healing in the coming weeks. In the meantime, put a vase full of fresh flowers beside your bed. You’ll feel better in the morning.