Ideas and Free Throws

Assume, for a moment, that I’m your manager. I call you into my office one day and say, “You’re doing pretty good work … but you’re going to have to get better at shooting free throws on the basketball court. If you want a promotion this year, you’ll need to make at least 75% of your free throws.”

What would you do? Assuming that you don’t resign on the spot, you would probably get a basketball, go to the free throw line, and start practicing free throws (also known as foul shots). Like most skills, you would probably find that your accuracy improves with practice. You might also hire a coach or watch some training videos, but the bottom line is practice, practice, practice.

Now, let’s change the scenario. I call you into my office and say, “You’re doing pretty good work … but you’re going to have to get better at creating ideas. If you want a promotion this year, you’ll need to increased the number of good ideas you generate by at least 75%.”

Now what? Well … I’d suggest that you start practicing the art of creating good ideas. In fact, I’d suggest that it’s not very different from practicing the art of shooting free throws.

But shooting free throws and creating ideas seem to be very different processes. Here’s how they feel:

- Shooting free throws – you get a basketball, you walk to the line – 15 feet from the basket – and you launch the ball into the air. You’re conscious of every action. You recognize that you’re the cause and a flying basketball is the result.

- Creating ideas – nothing happens … then, while you’re walking down the street, minding your own business – poof! – a good idea pops into mind. You have no sense of agency. Instead of feeling like the cause, you feel like the effect.

The two activities seem very different but, actually, they’re not. In both cases, you’re doing the work. With free throws, you readily recognize what you’re doing. With ideas, you don’t. Free throws happen in your conscious mind, also known as System 2. New ideas, on the other hand, happen below the level of consciousness, in System 1. When System 1 works up an idea, it pops it into System 2 and you become aware of it.

We understand how to practice something in System 2 – we’re aware of our activity. But how do we practice in System 1? How can we practice something that we’re not aware of?

We think of our mind as controlling our body. But, as Amy Cuddy has pointed out, our bodily activities also influence our mental states. If we make ourselves big, we grow more confident. If we smile, our mood brightens.

So how do we use our bodies to teach our brains to have good ideas? First, we need to observe ourselves. What were you doing the last time you had a good idea? I’ve noticed that most of my good ideas pop into my head when I’m out for a walk. When I’m stuck on a difficult problem, I recognize that I need a good idea. I quit what I’m doing and go for a walk. Oftentimes, it works – my System 1 generates an idea and pops it into System 2.

In my critical thinking classes, I ask my students to raise their hands if they have ever in their lives had a good idea. All hands go up. Everybody has the ability to create good ideas. The question is practice.

Then I ask my students what they were doing the last time they had a good idea. The list includes: out for a walk, driving, riding in a car, bus, or train (but not an airplane), taking a shower, drifting off to sleep, and bicycling.

I also ask them what activities don’t generate good ideas. The list includes: when they’re stressed, highly focused, multitasking, overly tired, overly busy, or sitting in meetings.

So how do we practice the art of having good ideas? By doing more of those activities that generate good ideas (and fewer of those that don’t). The most productive activities – like walking – seem to occupy part of our attention while leaving much of our brainpower free to wander somewhat aimlessly. Our bodily activity influences and stimulates our System 1. The result is often a good idea.

Is that perfectly clear? Good. I’m going for a walk.

Posture, Attitude, and Amy Cuddy

Power Pose.

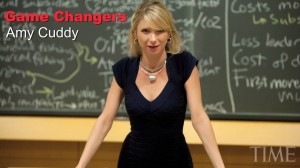

Suellen and I went to the Tattered Cover bookstore (a Denver icon) last night to hear Amy Cuddy speak about her new book, Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self To Your Biggest Challenges.

I’ve written about Cuddy before (here, here, and here) and use some of her work in my Critical Thinking class. We all have a general understanding of how the mind affects the body. Cuddy asks us to consider the reverse – how does the body affect the mind? Cuddy points out that the way we carry ourselves – our posture and body language – can affect our mood, thoughts, and performance. She introduces the topic quite well in her famous TED talk – the second most watched TED talk ever.

Cuddy writes that our posture affects our power over ourselves (as opposed to power over other people). When we adopt an expansive posture – making ourselves big – our power to manage ourselves and perform optimally increases. When we adopt a drawn-in posture – making ourselves small – we give away power over our own performance.

Cuddy has covered this ground before (here and here, for instance). So, what’s new? Here’s what I learned in last night’s talk:

- It’s not about outcomes; it’s about process – Cuddy gets thousands of e-mails from people who explain that they didn’t do well in a challenging process, like a job interview or an audition. But they’re not asking for advice on how to change the outcome. Instead, they’re asking how to perform the process better. This strikes me as being akin to decision theory — judging decision quality focuses on the process, not the outcome.

- It’s about your authentic self – when we are present, our body language and our spoken language reinforce each other. When we’re not present, our body language tells a different story than our spoken language.

- Two minutes is overemphasized – in her TED talk, Cuddy explains that holding an expansive posture – a power pose – for two minutes will change our hormones in positive ways. She explained last night that two minutes is not a magic number; even a few seconds is helpful.

- Animals helped us develop this idea … — Cuddy noted the influence of the naturalist Frans de Waal who explained, in his classic book, Chimpanzee Politics, how chimps adopt expansive postures to get what they want.

- … and we can, in turn, help animals – a horse trainer (@seriouspony) who was familiar with Cuddy’s work tried posture therapy on one of her Icelandic ponies who was suffering from “profound depression”. Here’s a video that shows the results.

- It has an impact on PTSD – Cuddy mentioned her friend and fellow researcher, Emma Seppälä, who has used posture therapy on combat veterans with PTSD. The results are encouraging.

- Gender – little boys and girls are equally likely to adopt expansive poses. But by the age of six (roughly) girls are starting to adopt more drawn-in poses while boys continue to be expansive. Cuddy suggests that, if we want to promote gender equality, we might start by changing this learned behavior.

- Imagination – it’s not always convenient to strike a power pose. Cuddy believes that simply imagining yourself in a power pose can be beneficial.

- Even the master needs reminders – Cuddy explained how an Internet troll had put her in a funk. Her husband reminded her to check and change her body language. She now carries a copy of her own book with a hand written note: “Remember to take your own advice”. Bottom line – we need to think about our body language; it doesn’t just change by itself.

- Where to next? – Cuddy’s many correspondents have noted that people on the autism spectrum and people with dementia both tend to adopt drawn-in postures. They make themselves small. Cuddy wonders if helping them learn to make themselves big would help.

Cuddy is a fascinating speaker – her body language definitely reinforces here spoken language. I recommend the book. Just remember that were you stand depends on how you stand.

The Dreaded iHunch

Now look at your phone.

We know that smart phones are bad for your posture. And we know that posture has a strong influence on mood, attitude, and performance. So, could smart phones be undermining your mood and deflating your performance? Of course they could.

Let’s review what we know about two key ideas:

Smart phones and posture – we know that people tilt their heads forward to read their smart phones. The trendy term for this is iHunch. Anatomists more frequently refer to it as forward head posture in which the ear is “…forward of the shoulder rather than sitting directly over it.” As the authors at What’s Your Posture note, it’s like hanging a bowling ball around your neck and reduces lung capacity by as much as 30%. It’s also associated with “headaches, abnormal functions of the eyes and ears, and psychological and mental disorders.” Yikes!

Posture and performance – the concept of embodied cognition suggests that we think with our bodies as much as our minds. If we smile, our mood will improve. If we stand up straight, our confidence will improve. If we support an idea, we’ll stand up for it. If we want to help someone, we’ll bend over backwards for them. In very literal ways, our posture affects our mood and performance.

As Amy Cuddy pointed out in her popular TED talk, if we adopt a high-power pose for two minutes, our levels of testosterone increase and levels of cortisol decrease. The effect is to increase dominance and reduce stress. We’re more confident and our performance improves.

On the other hand, if we hold a low-power pose for two minutes, testosterone falls and cortisol rises. We’re more stressed and less confident. Our performance suffers.

What does a low-power pose look like? Well, … it looks a lot like the posture we adopt when we look at our smart phones. In a low-power pose, we make ourselves smaller. We draw ourselves in. We take up less space rather than more. In a smart phone posture we’re essentially doing all of those things at once.

As Cuddy pointed out in yesterday’s New York Times, “When we’re sad, we slouch. We also slouch when we feel scared or powerless. Studies have shown that people with clinical depression adopt a posture that eerily resembles the iHunch.” By slouching over our phones, we’re making ourselves sad, fearful, and depressed.

When we look at our smart phones, we absorb new information. That information could be positive or negative. The posture we use, however, increases our stress and reduces our confidence. That tends to undermine the positive news and accentuate the negative news. We stress ourselves through our postures as much as our news sources.

What to do? As my father (a good military man) frequently reminded me, “Stand up straight. Look sharp, be sharp”. As it turns out, Dad was right. Oh… and breathe deeply, hold your head up, and take up more space rather than less. You feel better already, don’t you?

Should You Talk To Yourself?

Speak to me, wise one.

The way we think about the world comes from our body, not from our mind. If I like somebody, I might say, “I have warm feelings for her.” Why would my feelings be warm? Why wouldn’t I say, “I have orange feelings for her”? It’s probably because, when my mother held me as an infant, I was nice and toasty warm. I didn’t feel orange. I express my thoughts through metaphors that come from my body.

We all know that our minds affect our bodies. If I’m in a good mood mentally, my body may feel better as well. As I’ve noted before, the reverse is also true. It’s hard to stay mad if I force myself to smile.

The general field is referred to as metaphor theory or, more generally, as embodied cognition. Simply put, our bodies affect our thinking. Our brains are not digital computers, after all. They’re analog computers, using bodily metaphors to express our thoughts.

As it happens, I’ve used embodied cognition for years without realizing it. Before giving a big speech, I stand up straighter, flex my muscles, stretch out and up, and force myself to smile for 30 seconds. Then I’m ready. I didn’t realize it but I was practicing my bodily metaphors. I can speak more clearly (stand up straight), more powerfully (muscle flexing), and more cheerfully (smile), because of my warm-up routine.

My warm-up routine actually changes my hormones. As Amy Cuddy points out in her popular TED talk, practicing “power poses” for two minutes increases testosterone and reduces cortisol. The result is more dominance (testosterone) and less stress (cortisol). My body is priming me to give an exceptionally good speech. As Cuddy notes, it could also make me much more successful in a job interview.

I’m growing accustomed to the thought that the way I hold or move my body directly affects my thinking and mood. But what about my internal monologue? I talk to myself all the time. Is that a good thing? Do the words that I use in my monologue affect my thinking and behavior?

The answer is yes – for better and for worse. My “self-talk” affects how I perceive myself and that, in turn, affects how I behave. It’s also important how I address myself. Do I speak to myself in the first person – “I can do better than that.” Or do I speak to myself as someone else would speak to me – “Travis, you can do better than that.”

According to a recent article in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, the way I address myself makes a world of difference. If I speak as another person would address me, I gain more self-distance and perspective. I also reduce stress and make a better first impression. I can also give a better speech and will engage in “less maladaptive postevent processing”. (Whew!) In other words, I can perform better and feel better simply by choosing the right words in my internal monologue.

So, what’s it all mean? Take better care of your body to take better care of your mind. As my father used to say: “Look sharp, be sharp”. Oh… and watch your language.

(For an excellent article on how the field of embodied cognition has evolved, click here).