Posture, Attitude, and Amy Cuddy

Power Pose.

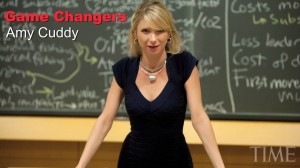

Suellen and I went to the Tattered Cover bookstore (a Denver icon) last night to hear Amy Cuddy speak about her new book, Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self To Your Biggest Challenges.

I’ve written about Cuddy before (here, here, and here) and use some of her work in my Critical Thinking class. We all have a general understanding of how the mind affects the body. Cuddy asks us to consider the reverse – how does the body affect the mind? Cuddy points out that the way we carry ourselves – our posture and body language – can affect our mood, thoughts, and performance. She introduces the topic quite well in her famous TED talk – the second most watched TED talk ever.

Cuddy writes that our posture affects our power over ourselves (as opposed to power over other people). When we adopt an expansive posture – making ourselves big – our power to manage ourselves and perform optimally increases. When we adopt a drawn-in posture – making ourselves small – we give away power over our own performance.

Cuddy has covered this ground before (here and here, for instance). So, what’s new? Here’s what I learned in last night’s talk:

- It’s not about outcomes; it’s about process – Cuddy gets thousands of e-mails from people who explain that they didn’t do well in a challenging process, like a job interview or an audition. But they’re not asking for advice on how to change the outcome. Instead, they’re asking how to perform the process better. This strikes me as being akin to decision theory — judging decision quality focuses on the process, not the outcome.

- It’s about your authentic self – when we are present, our body language and our spoken language reinforce each other. When we’re not present, our body language tells a different story than our spoken language.

- Two minutes is overemphasized – in her TED talk, Cuddy explains that holding an expansive posture – a power pose – for two minutes will change our hormones in positive ways. She explained last night that two minutes is not a magic number; even a few seconds is helpful.

- Animals helped us develop this idea … — Cuddy noted the influence of the naturalist Frans de Waal who explained, in his classic book, Chimpanzee Politics, how chimps adopt expansive postures to get what they want.

- … and we can, in turn, help animals – a horse trainer (@seriouspony) who was familiar with Cuddy’s work tried posture therapy on one of her Icelandic ponies who was suffering from “profound depression”. Here’s a video that shows the results.

- It has an impact on PTSD – Cuddy mentioned her friend and fellow researcher, Emma Seppälä, who has used posture therapy on combat veterans with PTSD. The results are encouraging.

- Gender – little boys and girls are equally likely to adopt expansive poses. But by the age of six (roughly) girls are starting to adopt more drawn-in poses while boys continue to be expansive. Cuddy suggests that, if we want to promote gender equality, we might start by changing this learned behavior.

- Imagination – it’s not always convenient to strike a power pose. Cuddy believes that simply imagining yourself in a power pose can be beneficial.

- Even the master needs reminders – Cuddy explained how an Internet troll had put her in a funk. Her husband reminded her to check and change her body language. She now carries a copy of her own book with a hand written note: “Remember to take your own advice”. Bottom line – we need to think about our body language; it doesn’t just change by itself.

- Where to next? – Cuddy’s many correspondents have noted that people on the autism spectrum and people with dementia both tend to adopt drawn-in postures. They make themselves small. Cuddy wonders if helping them learn to make themselves big would help.

Cuddy is a fascinating speaker – her body language definitely reinforces here spoken language. I recommend the book. Just remember that were you stand depends on how you stand.

Should You Talk To Yourself?

Speak to me, wise one.

The way we think about the world comes from our body, not from our mind. If I like somebody, I might say, “I have warm feelings for her.” Why would my feelings be warm? Why wouldn’t I say, “I have orange feelings for her”? It’s probably because, when my mother held me as an infant, I was nice and toasty warm. I didn’t feel orange. I express my thoughts through metaphors that come from my body.

We all know that our minds affect our bodies. If I’m in a good mood mentally, my body may feel better as well. As I’ve noted before, the reverse is also true. It’s hard to stay mad if I force myself to smile.

The general field is referred to as metaphor theory or, more generally, as embodied cognition. Simply put, our bodies affect our thinking. Our brains are not digital computers, after all. They’re analog computers, using bodily metaphors to express our thoughts.

As it happens, I’ve used embodied cognition for years without realizing it. Before giving a big speech, I stand up straighter, flex my muscles, stretch out and up, and force myself to smile for 30 seconds. Then I’m ready. I didn’t realize it but I was practicing my bodily metaphors. I can speak more clearly (stand up straight), more powerfully (muscle flexing), and more cheerfully (smile), because of my warm-up routine.

My warm-up routine actually changes my hormones. As Amy Cuddy points out in her popular TED talk, practicing “power poses” for two minutes increases testosterone and reduces cortisol. The result is more dominance (testosterone) and less stress (cortisol). My body is priming me to give an exceptionally good speech. As Cuddy notes, it could also make me much more successful in a job interview.

I’m growing accustomed to the thought that the way I hold or move my body directly affects my thinking and mood. But what about my internal monologue? I talk to myself all the time. Is that a good thing? Do the words that I use in my monologue affect my thinking and behavior?

The answer is yes – for better and for worse. My “self-talk” affects how I perceive myself and that, in turn, affects how I behave. It’s also important how I address myself. Do I speak to myself in the first person – “I can do better than that.” Or do I speak to myself as someone else would speak to me – “Travis, you can do better than that.”

According to a recent article in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, the way I address myself makes a world of difference. If I speak as another person would address me, I gain more self-distance and perspective. I also reduce stress and make a better first impression. I can also give a better speech and will engage in “less maladaptive postevent processing”. (Whew!) In other words, I can perform better and feel better simply by choosing the right words in my internal monologue.

So, what’s it all mean? Take better care of your body to take better care of your mind. As my father used to say: “Look sharp, be sharp”. Oh… and watch your language.

(For an excellent article on how the field of embodied cognition has evolved, click here).

False Smile, Real Purchase

Is that a real smile?

As we’ve discussed before, your body influences your mood. If you want to improve your mood, all you really have to do is force yourself to smile. It’s hard to stay mad or blue or shiftless when your face is smiling.

I can’t prove this but I think that smiling can also improve your performance on a wide variety of tasks. I suspect that you make better decisions when you’re smiling. I bet you make better golf shots, too.

It’s not just my face that influences my mood. It’s also the faces of those around me. If they’re smiling, it’s harder for me to stay mad. There’s a lot written about the influence of groups on individual behavior.

Retailers seem to understand this intuitively. I occasionally go to jewelry stores to buy something for Suellen. I notice two things: 1) I’m always waited on by a woman; 2) she smiles a lot. I assume that she smiles to influence my mood (positively) to increase the chance of making a sale. It often works.

I understand the reason behind a false smile on another person (and, most often, I can defend against it). But what if the salesperson uses my own smile to influence my mood and propensity to buy?

It could happen soon. As reported in New Scientist, the Emotion Evoking System developed at the University of Tokyo, can manipulate your image so you see a smiling (or frowning) version of yourself. The system takes a webcam image of you and manipulates it to put a smile on your face. It then displays the image to you. It’s like looking in the mirror but the image isn’t a faithful replication.

In preliminary tests, volunteers were divided into two groups and asked to perform mundane tasks. Both groups could see themselves in a webcam image. One group saw a plain image. The other group saw a manipulated image that enhanced their smile. Afterwards, the volunteers in each group were asked to rate their happiness while performing the task. The group that saw the manipulated image reported themselves to be happier.

In theory, such a system could help people who are depressed. It could also be used to sell more. You try on something and see a smiling version of you in the mirror. As they say, buyer beware!

Verbal, Vocal, Visual – Body Language and You

Let me explain quantum mechanics.

A woman says to a man, “Oh, you’re such a brute.” What does she mean? Well, it depends. The words have meaning in themselves but the way they’re delivered also counts for something.

Let’s say that she delivers the line with an aggressive posture, a scowl on her face, and a harsh tone in her voice. Most of us would conclude that the man should take her words literally; she’s angry and the man should back off.

On the other hand, let’s say she delivers the same line with a smile on her face, a flirtatious giggle in her voice, and a soft, inviting posture. She uses the same words but delivers them in a very different way. Most people would conclude that she doesn’t mean for her words to be taken literally. What she does mean may not be crystal clear but it’s probably not the literal words she speaks. (By the way, I adapted this example from an excellent article in New Scientist).

This is what Albert Mehrabian, the father of the so-called 7%-38%-55% rule, was studying. Mehrabian was trying to identify how face-to-face communication actually transpires, especially when the words are ambiguous. He identified three basic components: 1) the words themselves; 2) tone of voice; and 3) body language, including facial expressions. These are often summarized as the three V’s – verbal, vocal, visual.

In ambiguous situations, especially when discussing feelings, how do you sort out what the other person means? Mehrabian calculated that the words themselves account for 7% of the meaning (from the perspective of the receiver). Tone-of-voice accounts for 38% of the meaning, and body language accounts for 55%. To determine whether you’re really a brute or not, you should probably pay less attention to what the woman says and more attention to how she says it. (For more on the multiple meanings of simple words, click here).

Mehrabian’s findings may be accurate in the very specific case of conveying feelings in face-to-face communication. Unfortunately, far too many “experts” have over-extrapolated the data and applied it to all communications. When you give a speech, for instance, they may claim that 93% of what the audience receives comes from tone-of-voice and body language.

If that were really true, then why speak at all? If 93% of meaning comes from non-verbal channels, a good mime should be able to deliver a speech just as well as you can. Indeed, if 93% of communication is non-verbal, then why do we bother to learn foreign languages?

Fortunately or unfortunately, even Marcel Marceau (pictured) can’t effectively deliver an information-laden speech without words. Words are important – use them wisely and use them sparingly. Body language is also important. The best advice on body language is simple: you should appear comfortable and confident to your audience. If you don’t, your audience will wonder what you’re hiding. If you do appear comfortable and confident, your audience will attend to your words – for much more than 7% of the meaning.

Tips on Body Language

When you’re speaking in public, your primary physical objective is to appear comfortable and confident on stage. Many coaches specializing in presentation training will give you very specific tips on how to use body language to your advantage, but the primary tip is to do whatever makes you feel Continue reading