Making Friends in Nine Minutes

What if we could make friends more quickly and more predictably? Would we make more friends? Would life be better? Would we be happier? Would we take fewer tranquilizers?

What if we could make friends in nine minutes?

We usually think of making friends as a pleasurable process. We don’t usually think of it as a necessary process. We could, I suppose, survive reasonably well without making friends. But what if you have to make friends? How would you do it?

This is a problem that faces some social science researchers. If you want to study relationships – how they form, how they influence behavior, etc. – you need to be able to create relationships and measure their degree of closeness.

For instance, you might want to study the effect of friendship on, say, pro-social behavior. Do people in friendly relationships do more good works or fewer? You invite pairs of friends to participate. Assume that you want to compare pairs of people who have been friends for less than six months. You could sort through pairs of people to find those who fit your criteria. But it’s complicated and imprecise.

Alternatively, you could recruit strangers, pair them up randomly, and induce friendships among them. What’s the advantage? Constantine Sedikides and his colleagues wrote about this in their paper, “The Relationship Closeness Induction Task.” They note that “Because newly formed laboratory relationships lack a history of … past interactions, … the researcher is able to examine the effect of relationship closeness per se on the dependent measurements….” Random assignment also reduces the impact of pesky intervening variables.

The methodological advantage seems clear. But … how do you induce a friendship? Sedikides et. al. describe several methods that didn’t seem to work very well. They then propose the Relationship Closeness Induction Task (RCIT) which is built on “… the principle that a vital feature in the development of a close relationship is reciprocal and escalating self-disclosure.” In simpler terms, by sharing information about yourself (self-disclosing) with a stranger who also shares information, you develop a closer relationship.

The RCIT consists of three lists of questions – 29 questions total — and participants are asked to spend nine minutes “mutually self-disclosing”. They spend one minute on List 1, three minutes on list II, and five minutes on List III. The authors note that the RCIT has proved its validity in four different ways:

- Participants reported a higher level of relationship closeness than did control groups, with no gender differences found.

- RCIT induced closeness created statistically significant impacts on dependent variables in several different studies.

- Participants reported that they had adequate privacy and felt comfortable with the process.

- In the allotted nine minutes, participants answered 90% of the questions.

The original questions were written for college students; they’re the most likely participants in these kinds of studies. With just a bit of imagination, however, you could pull out the college-related questions and substitute other, more relevant questions in your friendship induction process.

I suspect by now that you would like to know the 29 questions. Here they are. Now go out and make some friends. You’ve got nine minutes.

List I – One minute

- What is your name?

- How old are you?

- Where are you from?

- What year are you in at University X?

- What do you think you might major in? Why?

- What made you come to the University of X?

- What’s your favorite class at the University of X? Why?

List II – Three minutes

- What are your hobbies?

- What would you like to do after graduation from the University of X?

- What would be the perfect lifestyle for you?

- What is something you have always wanted to do but probably never will be able to do?

- If you could travel anywhere in the world, where would you go and why?

- What is one strange thing that has happened to you since you have been at the University of X?

- What is one embarrassing thing that has happened to you since arriving at the University of X?

- What is one thing happening in your life that makes you stressed out?

- If you could change anything that happened to you in high school, what would that be?

- If you could change one thing about yourself what would that be?

- Do you miss your family?

- What is one habit you’d like to break?

List III – Five minutes

- If you could have one wish granted, what would that be?

- Is it difficult or easy for you to meet people? Why?

- Describe the last time that you felt lonely.

- What is one emotional experience you’ve had with a close friend?

- What is one of your biggest fears?

- What is your most frightening early memory?

- What is your happiest early childhood memory?

- What is one thing about yourself that most people would consider surprising?

- What is one recent accomplishment that you are proud of?

- Tell me one thing about yourself that most people who already know you don’t know.

What’s Walking Good For?

I often ask my students a simple question: What were you doing the last time you had a good idea? Whatever they answer, I say: “Do more of that and you’ll have more good ideas.”

So what are they doing when they have good ideas? A fair number – often a majority – are walking. Taking a break and going for a walk stimulates our thinking in ways that produce interesting and novel ideas. Walking takes a minimum amount of conscious effort; we have plenty of mental bandwidth left for other interesting thoughts. Walking also provides a certain amount of stimulation. The sights and sounds and smells trigger memories and images that we can combine in novel ways. By moving our bodies slowly, we create thoughts that move much more quickly.

Going for a walk with a friend, colleague, or loved one can also help us create richer, deeper conversations. Walking stimulates novel thoughts; if a companion is beside us, we can share those thoughts immediately. The back-and-forth can lead us into new territory. A good conversation is not just an exchange of existing ideas. Rather, it produces new ideas – and walking can help.

Walking can also help us have difficult conversations. The key here may be our posture and proximity rather than walking per se. When we walk with another person, we are typically side-by-side, not face-to-face. We’re not confronting each other physically. We’re talking to the air, rather than at each other. We’re slightly insulated from each other, which makes it easier to both make and receive blunt statements.

According to Walk-And-Talk therapists like Kate Hays, walking can also enhance traditional psychotherapy sessions. Walking with a therapist “…spurs creative, deeper ways of thinking often released by mood improving physical activity.” Walking seems especially helpful when the conversation is between a parent and, say, a teenager. We feel close, but not intimidated. (Side note: we often describe deep conversations as “heart-to-heart” but rarely describe them as “face-to-face.”)

What else can walking do? It’s an “active fingerprint.” As the MIT Technology Review puts it, “… your gait [is} a very individual and hard-to-imitate trait.” In other words, the way you walk uniquely identifies you.

Clearly, we can use gait-based identification for positive or negative ends. With so many security cameras in place today, we’re rightly concerned about facial recognition as an invasion of privacy. But we can hide our faces with something as simple as a surgical mask. Disguising the way we walk is much more difficult.

On the other hand, think of a device – perhaps a smart phone – that can uniquely identify you based solely on your gait. You put your phone in your pocket and walk along; it “knows” who you are. Rather than depending on fingerprints or passwords, the device simply monitors your gait. One benefit is convenience – you don’t have to enter a password every time you want to use the device. The second benefit is perhaps more important: security. A thief could steal your password or even an image of your fingerprint. But could they imitate your gait? Probably not.

What else is walking good for? Oh, simple things like health, flexibility, weight loss, mental acuity, sociability, and so on. I’d like to hear your stories about the benefits of walking. Just send me an e-mail. I’ll read them after I get back from my walk.

Tongue-tied On Valentine’s Day?

Valentine’s cards intrigue me. Suellen and I exchange them every year. Some are sweet. Some are funny. Some are silly. Some are mildly sexy. But really, is there anything new in them? Have we come a long way, baby, or are we just recycling platitudes? And how did people in past centuries address their love, passion, and heartaches? What can we learn from our ancestors?

Valentine’s cards intrigue me. Suellen and I exchange them every year. Some are sweet. Some are funny. Some are silly. Some are mildly sexy. But really, is there anything new in them? Have we come a long way, baby, or are we just recycling platitudes? And how did people in past centuries address their love, passion, and heartaches? What can we learn from our ancestors?

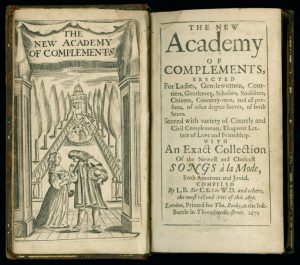

By happy accident, I discovered a partial answer in the Newberry Library in Chicago. The Newberry holds a copy of The New Academy of Complements published in London in the 17th century. The small book – easily tucked in a pocket — is addressed to “both Sexes” and contains a “variety of Courtly and Civil complements” as well as “Eloquent Letters of Love and Friendship … both amorous and jovial.” Happily, the compliments are compiled by “the most refined Wits of the Age.”

What were the best amorous compliments of 17thcentury England? Here are a few of my favorite selections. *

Complemental Expressions towards Men, Leading to The Art of Courtship.

Sir, Your Goodness is as boundless, as my desires to serve you.

Sir, You are so highly generous, that I am altogether senceless.

Sir, You are so noble in all respects that I have learn’d to love, as well as to admire you.

Sir, Your Vertues are so well known, you cannot think I flatter.

Complements towards Ladies, Gentlewomen, Maids, &c.

Madam, When I see you I am in paradice, it is then that my eyes carve me out a feast of Love.

Madam, Your beauty hath so bereav’d me of my fear, that I do account it far more possible to die, than to forget you.

Madam, Since I want merits to equallize your Vertues, I will for ever mourn for my imperfections.

Madam, You are the Queen of Beauties, your vertues give a commanding power to every mortal.

Madam, Had I a hundred hearts I should want room to entertain your love.

I don’t have room to quote many of the gems contained in the book, but here are a few of the categories. Each category provides several models of what to say or write to address the situation. Who knows – you might need one from time to time.

A Gentleman of good Birth, but small Fortune, to a worthy Lady, after she had given a denial.

The Ingratiating Gentleman to his angry Mistriss.

The Lover to his Mistriss, upon his fear of her entertaining a new Servant.

The Jealous Lover to his beloved. The Answer: A Lady to her Jealous Lover.

A crack’t Virgin to her deceitful Friend, who hath forsook her for the love of a Strumpet.

A Lover to his Mistriss, who had lately entertained another Servant to her bosom, and her bed. The Answer: The Lady to her Lover, in defence of her own Innocency.

As you can see, The Academy provides the words to address (and perhaps remedy) most any situation. Is a bald man bothering you? Here’s how to respond:

Sir…while I could be content to keep my Coaches, my Pages, Lackeys, and Maids, I confess I could never endure the society of a bald pate.

I think the Newberry might find an interesting niche market by publishing high quality Valentine’s cards with extracts from The Academy. I know I would buy some. In the meantime, I hope you can find an appropriate quote for whatever your needs are this Valentine’s Day

* The edition held by the Newberry Library was published in 1671. The selections in this article are drawn from the 1669 edition

Don’t Argue In The Past Tense

Let’s say that Suellen and I have an argument and I notice that all the verbs are in the past tense. According to Aristotle, the verbs tell us that the argument is about blame. I may think it’s about who left the door unlocked or forgot to pay the mortgage. But it’s really about blame.

Let’s also say that I win that argument. (This is very hypothetical). I’ve successfully pushed the blame away from myself and on to her. It’s not easy to win an argument, so I do a little victory dance. Meanwhile, how does Suellen feel? Probably a mixture of emotions – irritation, annoyance, anger, … perhaps even a desire to get even. Suellen is the woman I love. Why on earth would I want her to feel like that? That’s the problem with arguing in the past tense. Even if you win, you lose.

Arguing in the past tense is generally known as forensic rhetoric. In many legal situations, we do want to lay blame. We want to establish guilt and make sure that the appropriate person is appropriately punished. Most of the testimony in a trial is in the past tense. Similarly, characters in crime dramas speak almost exclusively in the past tense. The goal is to lay blame and Aristotle and others give us rules for how to argue the point.

Outside of the courtroom, however, arguing in the past tense is essentially useless. We can’t do anything about the past. We can’t change it. We can’t enhance it. We can lay blame but, even then, we will argue endlessly about whether we got it right or not. Did we blame the right person? If so, did we blame them for the right reasons? Did we learn the right lessons? Did history teach us anything? Or did it teach us nothing?

The next time you’re in an argument, notice the verbs. If they’re in the past tense, you’re simply trying to blame the other person. Does it do any good to “win” such an argument? Nope. By “winning”, you just give the other side motivation to come back stronger next time. This is how feuds get started. The Stoic philosopher, Epictetus, had it right: “Small-minded people blame others. Average people blame themselves. The wise see all blame as foolishness.”

The Dying Grandmother Gambit

I teach two classes at the University of Denver: Applied Critical Thinking and Persuasion Methods and Techniques. Sometimes I use the same teaching example for both classes. Take the dying grandmother gambit, for instance

In this persuasive gambit, the speaker plays on our heartstrings by telling a very sad story about a dying grandmother (or some other close relative). The speaker aims to gain our agreement and encourages us to act. Notice that thinking is not required. In fact, it’s discouraged. The story often goes like this:

My grandmother was the salt of the earth. She worked hard her entire life. She raised good kids and played by the rules. She never complained; she just worked harder. She worked her fingers to the bone but she was always the picture of health … until her dying days when our government simply abandoned her. As her health failed, she moved into a nursing home. She wanted to stay. She thought she had earned it. But the government did X (or didn’t do Y). As a result, my dying grandmother was abandoned to her fate. She was kicked to the curb like an old soda can. In her last days, she was a tiny, wrinkled prune. She couldn’t hear or see. She just curled up in her bed and waited to die. But our faceless bureaucrats couldn’t have cared less. My grandmother never complained. That was not her way. But she cried. Oh lord, did she cry. I can still see the big salty tears rolling slowly down her cheeks. Sometimes her gown was soaked with tears. How much did the government care? Not a whit. It would have been so easy for the government to change its policy. They could have cancelled X (or done Y). But no, they let her die. Folks, I don’t want your grandparents to die this way. So I’ve dedicated my candidacy to changing the government policy. If I can save just one grandma from the same fate, I’ll consider my job done.

So, do I tell my classes this is a good thing or a bad thing? It depends on which class I’m teaching.

In my critical thinking class I point out the weakness of the evidence. It doesn’t make sense to decide government policy on a sample of one. Perhaps the grandmother represents a broader population. Or perhaps not. We have no way of knowing how representative her story is.

Further, we didn’t meet the dear old lady. We didn’t directly and dispassionately observe her conditions. We didn’t speak to her caretakers. Or to those faceless bureaucrats. We only heard the story and we heard it from a person who stands to benefit from our reaction. She may well have embroidered or embellished the story.

Further, the speaker is playing on the vividness fallacy. We remember vivid things, especially things that result in loss, or death, or dismemberment. Because we remember them, we overestimate their probability. We think they’re far more likely to happen than they really are. If we invoke our critical thinking skills, we may recognize this. But the speaker aims to drown our thinking in a flood of emotions.

In my critical thinking class, I point out the hazards of succumbing to the story. In my persuasion class, on the other hand, I suggest that it’s a very good way to influence people.

The dying grandmother is a vivid and emotional story. It flies below our System 2 radar and aims directly at our System 1. It aims to influence us emotionally, not conceptually. It’s influential because it’s a good story. A story can do what data can never do. It can engage us and enrage us.

Further, the dying grandmother puts a very effective face on the issue. The issue is no longer about numbers. It’s about flesh and blood. We would be very hardhearted to ignore it. So we don’t ignore it. Instead, our emotions pull us closer to the speaker’s position.

So is the dying grandmother gambit good or bad? It’s neither. It just is. We need to recognize when someone manipulates our emotions. Then we need to put on our critical thinking caps.