Rhetorical Jujitsu

Lovely place Brixham

The United Kingdom is deeply embroiled in the Brexit debate. It’s the classic question: should we stay or should we go? Polls suggest that the electorate is almost evenly split. What can this teach us about persuasion?

Let’s take an example from a man with an opinion. Michael Sharp is a fisherman from the lovely little port of Brixham on the south coast of England who favors leaving the EU. The New York Times quotes him as saying,

“I definitely want out. … All those wars we’ve had with France, Germany — all the rest of them since God knows when, since Jesus was a lad — we’re never going to get on with them, are we?”

Now imagine that you support the opposite side – you think the UK should stay in the EU. How might you persuade Mr. Sharp to agree with you? Here are four different rhetorical approaches you might try:

A) “What a silly thing to say. We’re friends with France and Germany now. You’re 70 years out of date.”

B) “What a parochial and small-minded attitude you have. You should broaden your horizons.”

C) “All the experts say we should stay in. The top bankers and managers say it will wreck the economy to leave.”

D) “I know what you’re saying. But I’ll tell you what I’m worried about. The Russians. If we’re squabbling with the French and Germans, the Russians will divide and conquer. That’s what they’re good at. It’ll be worse for all of us.”

Which alternative is best? As always, it depends on what you want to accomplish. Let’s look at the choices.

Alternatives A & B – in both cases, you strongly suggest to Mr. Sharp that he’s wrong, stubborn, and not very smart. If your goal is to feel superior to Mr. Sharp, this is a good strategy. On the other hand, if wish to persuade Mr. Sharp to your way of thinking, you’ve just shot yourself in the foot.

Alternative C – an appeal to authority can work in some situations. But not here. Many Brexit supporters think the authorities – better known as the elites – can’t be trusted. “They don’t care about us. They’ve sold us out. If they say we should stay, all the more reason to leave.” In this case, quoting the elites is self-defeating. (It’s probably a poor tactic in arguing with a Donald Trump supporter as well).

Alternative D – this is a rhetorical technique known as concession-and-shift. You begin by agreeing with the other person. In this case, you concede that Mr. Sharp is right. This makes you seem open-minded and reasonable (even if you’re not). Then you shift to new ground and bring in a different perspective. Since you’re open-minded, Mr. Sharp is more likely to be open-minded in return. He’s more likely to listen to your thoughts and understand your position. That’s the first step in persuading him to your point of view.

Concession-and-shift is a form of rhetorical jujitsu. You don’t push back. You don’t deny the other person’s position. You don’t try to humiliate the other side. Rather, you accept their position and move on. In its simplest form, you say, “You have a good point. But have you considered …”

Concession-and-shift can work in many different situations. It’s a useful tool to master and remember. And it helps us achieve the ultimate goal of rhetoric – to argue without anger.

Always Be Conversing

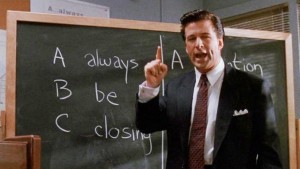

He was so young!

In the 1992 movie, Glengarry Glen Ross, Alec Baldwin played a very hard-nosed sales manager determined to teach a bunch of rookies how to sell. He used intimidation, fear, stress, and money as motivators. He didn’t believe in being nice. He believed in closing.

Baldwin also introduced a term that I’ve heard many times since: Always Be Closing or ABC. The idea is simple – you’re always looking for prospects, qualifying them, moving them through the sales process, and closing them. Then you start over. You’re like a shark – always moving, always eating.

Always Be Closing is associated with pushy, high-pressure sales tactics. You might find them in use at car dealerships or time-share condo conventions. We’re all familiar with them and we all profess to hate them.

Now what about nonprofits? Is Always Be Closing an appropriate technique for raising funds for a nonprofit organization? I don’t think so. For me, nonprofit fundraising is all about relationships. It’s about building for the long run, not closing in the short term.

So I’ve created a new ABC for non-profits: Always Be Conversing. A conversation, of course, has two parts: talking and listening. Always Be Conversing suggests that we’re always ready to talk about our nonprofit organization (NPO) and listen to our constituents’ needs. By conversing with constituents, friends, and our broader network of acquaintances, we build relationships. Over time, those relationships allow us – quite naturally – to ask for donations.

Always Be Conversing also implies that we actively seek out conversations. To create rich conversations, we need to prepare ourselves. Here are some pointers:

- Always have a story – people love stories – they’re easy to understand, relatable, and memorable. When you tell a story, you’re not being a pushy sales person. Rather, you’re building relationships, awareness, and interest. Tip: focus on outputs, not inputs. If your NPO donated a million dollars for scholarships last year, that’s an input. It’s an interesting fact but not a story. On the other hand, if you can describe how your scholarships changed people’s lives, that’s the output of your investment. It’s also a memorable story that most people will be eager to hear.

- Use conversation starters – how does anyone know that you’re passionate about your NPO? How does anyone know that you’re a source of information and assistance? The simplest way is to wear some identification. If you wear a lapel pin or a brooch or a jacket with your NPO’s logo on it, people can identify you and have a conversation. It can happen at random times, so always have a story ready.

- Don’t ask, offer– my NPO is the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. When I wear my NMSS jacket to the grocery store, people frequently ask me about my connection to the Society. Then they often say, “My (wife, cousin, mother, neighbor, etc.) has MS.” I typically respond by saying, “How can I help?” As it happens, NMSS can help in a variety of ways, from insurance advice to exercise programs. But I’m also invoking the reciprocity principle – you’re more persuasive if you offer a favor before requesting a favor.

Over the coming weeks, I’ll write more about fundraising for nonprofits through story telling and relationship building. In the meantime, start telling your stories. You’ll be surprised at the impact you can have.

(My NPO is the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. If you need information about multiple sclerosis or help in dealing with it, just drop me a line. I want to Always Be Conversing).

Posture, Attitude, and Amy Cuddy

Power Pose.

Suellen and I went to the Tattered Cover bookstore (a Denver icon) last night to hear Amy Cuddy speak about her new book, Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self To Your Biggest Challenges.

I’ve written about Cuddy before (here, here, and here) and use some of her work in my Critical Thinking class. We all have a general understanding of how the mind affects the body. Cuddy asks us to consider the reverse – how does the body affect the mind? Cuddy points out that the way we carry ourselves – our posture and body language – can affect our mood, thoughts, and performance. She introduces the topic quite well in her famous TED talk – the second most watched TED talk ever.

Cuddy writes that our posture affects our power over ourselves (as opposed to power over other people). When we adopt an expansive posture – making ourselves big – our power to manage ourselves and perform optimally increases. When we adopt a drawn-in posture – making ourselves small – we give away power over our own performance.

Cuddy has covered this ground before (here and here, for instance). So, what’s new? Here’s what I learned in last night’s talk:

- It’s not about outcomes; it’s about process – Cuddy gets thousands of e-mails from people who explain that they didn’t do well in a challenging process, like a job interview or an audition. But they’re not asking for advice on how to change the outcome. Instead, they’re asking how to perform the process better. This strikes me as being akin to decision theory — judging decision quality focuses on the process, not the outcome.

- It’s about your authentic self – when we are present, our body language and our spoken language reinforce each other. When we’re not present, our body language tells a different story than our spoken language.

- Two minutes is overemphasized – in her TED talk, Cuddy explains that holding an expansive posture – a power pose – for two minutes will change our hormones in positive ways. She explained last night that two minutes is not a magic number; even a few seconds is helpful.

- Animals helped us develop this idea … — Cuddy noted the influence of the naturalist Frans de Waal who explained, in his classic book, Chimpanzee Politics, how chimps adopt expansive postures to get what they want.

- … and we can, in turn, help animals – a horse trainer (@seriouspony) who was familiar with Cuddy’s work tried posture therapy on one of her Icelandic ponies who was suffering from “profound depression”. Here’s a video that shows the results.

- It has an impact on PTSD – Cuddy mentioned her friend and fellow researcher, Emma Seppälä, who has used posture therapy on combat veterans with PTSD. The results are encouraging.

- Gender – little boys and girls are equally likely to adopt expansive poses. But by the age of six (roughly) girls are starting to adopt more drawn-in poses while boys continue to be expansive. Cuddy suggests that, if we want to promote gender equality, we might start by changing this learned behavior.

- Imagination – it’s not always convenient to strike a power pose. Cuddy believes that simply imagining yourself in a power pose can be beneficial.

- Even the master needs reminders – Cuddy explained how an Internet troll had put her in a funk. Her husband reminded her to check and change her body language. She now carries a copy of her own book with a hand written note: “Remember to take your own advice”. Bottom line – we need to think about our body language; it doesn’t just change by itself.

- Where to next? – Cuddy’s many correspondents have noted that people on the autism spectrum and people with dementia both tend to adopt drawn-in postures. They make themselves small. Cuddy wonders if helping them learn to make themselves big would help.

Cuddy is a fascinating speaker – her body language definitely reinforces here spoken language. I recommend the book. Just remember that were you stand depends on how you stand.

Persuasion, Teens, and Tattoos

When our son, Elliot, was 17 he decided that he needed to get a Guinness logo tattooed on his ankle. I wasn’t adamantly opposed but I did think that he might tire of wearing a commercial logo before too long. (If he had wanted a Mom Forever tattoo, I might have felt differently).

When our son, Elliot, was 17 he decided that he needed to get a Guinness logo tattooed on his ankle. I wasn’t adamantly opposed but I did think that he might tire of wearing a commercial logo before too long. (If he had wanted a Mom Forever tattoo, I might have felt differently).

So how to convince him? I wanted to change his mind, though not his values. Nor did I want to provoke a stormy response that would simply make the situation worse – and actually make him more likely to follow through on his plans.

Ultimately, we had a conversation that went something like this:

Elliot: So, Dad, I’m thinking I should get a Guinness tattoo. It’s a really cool logo. What do you think?

Me: I don’t know. Do you think you’ll like Guinness for the rest of your life?

Elliot: Sure. It’s great. Why wouldn’t I?

Me: Well, you know, tastes change. I mean I thought about getting a tattoo when I was your age… and, looking back on it… I’m kind of glad I didn’t.

Elliot (shocked look): Really? You were going to get a tattoo?! What were you going to get?

Me: I wanted to get a dotted line tattooed around my neck. Right above the line, I’d get the words, “Cut On Dotted Line” tattooed in.

Elliot: (more shock, disgust): Dad, that’s gross.

Me: Oh, come on. Don’t you think it would be cool if I had that tattoo. I could show it to your friends. I bet they’d like it.

Elliot: They always thought you were weird. Now they’d think your gross. It’s yuck factor 12.

Me: Really? So, you don’t want to go to the tattoo parlor together?

Our conversation seemed to help Elliot change his mind. As far as I know, he hasn’t gotten any tattoos, not even Mom Forever. Why? Here are some thoughts:

It’s about trust, not tattoos – I don’t think that Elliot cared that much about the tattoo itself. He was actually running a Mom/Dad test. He wanted to know if we trusted him to make the decision on his own. We did trust him and didn’t take the decision out of his hands. That’s a big deal when you’re 17. It can also be a big deal for people in your company. They want to know that you trust them. Sometimes they’ll put it to a test. As much as possible, let them make the choice. Just counsel them on how to make it wisely.

It’s about judo — we didn’t try to stop Elliot, we merely tried to change his direction. That’s a useful guideline in most organizations.

It’s about imagining the future – like most teens, Elliot was focused on the present and near future. He couldn’t imagine 30 years into the future – except by looking at me. If he thought I would look gross with a tattoo, he could imagine that he would, too. The same is true of many companies. We make decisions based on near-term projections. It’s hard to imagine the farther future. But there are ways to do it. Ask your team to imagine what the world will look like in 30 years. You could start by reminding them how much it’s changed since 1985.

It’s about sharing – did I really think about getting a Cut On Dotted Line tattoo? Of course, I did. But my father sat me down and talked a little wisdom into my head. I just passed it on.

What are you going to pass on?

Somatopsychic Chewing Gum

No flu here!

Psychosomatic illness is one that is “caused or aggravated by a mental factor such as internal conflict or stress”. We know that the brain can create disturbances in the body. But what about the other way round? Can we have somatopsychic illnesses? Or could the body produce somatopsychic wellness – not a disease but the opposite of it?

I’ve written about embodied cognition in the past (here, here, and here). Our body clearly influences the way we think. But could our body influence the way we think and our thinking, in turn, influence our body? Here are some interesting phenomena I’ve discovered recently in the literature.

Exercise and mental health – I’ve seen a spate of articles on the positive effects of physical exercise on mental health. This truly is a somatopsychic effect. Among other things, raising your heartbeat increases blood flow to your brain and that’s a very good thing. Exercise also reduces stress, elevates your mood, improves your sleep, and – maybe, just maybe – improves your sex life.

Chewing gum and annoying songs – ever get an annoying song in your head that just won’t go away? For me, it’s the theme from Gilligan’s Island. New research suggests that chewing gum could alleviate – though not completely eliminate – the song. One researcher noted that, “producing movements of the mouth and jaw [can] affect memory and the ability to imagine music.” Why jaw movements would affect memory is anyone’s guess.

Hugs and colds – could hugging other people help you reduce your chances of catching a cold? You might think that hugging other people – especially random strangers – would increase your exposure to cold germs and, therefore, to colds. But it seems that the opposite is, in fact, the case. The more you hug, the less likely you are to get a cold. Hugging is a good proxy for your social support network. People with strong social support are less likely to get sick (or to die, for that matter). Even if you don’t have strong social support, however, increasing your daily quota of hugs seems to have a similar effect.

Sitting or standing? – do you think better when you’re sitting down or standing up? At least for young children – ages seven to 10 – standing up seems to produce much better results. Side benefit: standing at a desk can burn 15% to 25% more calories than sitting. Maybe this is why it’s a good thing to be called a stand-up guy.

Clean desk or messy desk (and here) – it depends on what behavior you’re looking for. People with clean desks are more likely “to do what’s expected of them.” They tend to conform to rules more closely and behave in more altruistic ways. People at messy desks, on the other hand, were more creative. The researchers conclude: “Orderly environments promote convention and healthy choices, which could improve life by helping people follow social norms and boosting well-being. Disorderly environments stimulated creativity, which has widespread importance for culture, business, and the arts.”

So, what does it all mean? As we’ve learned before, the body and the brain are one system. What one does affects the other. Behavior and thinking are inextricably intertwined. When your brain wanders, don’t let your feet loaf.