Spot The Fallacy

I recently saw an ad for Progressive Insurance that says, “Drivers who save with Progressive, save $796 on average.”

Now I like Progressive. And I love Flo. So, I’m sure that the statement is true. I’m sure it’s based on fact.

But it also entails a logical fallacy. If you don’t spot the fallacy, you may easily assume that the average savings for all drivers who switch to Progressive is $796. That would be a mistake.

This is a good example of the survivorship fallacy. We only examine cases that “survive” a certain threshold. In this case, the threshold is drivers who save. What about drivers who didn’t save?

Let’s say that we have 1,000 drivers who saved money. In fact, they saved a total of $796,000. On average, they saved $796 each.

Now let’s say that another 1,000 drivers saved nothing. Now we have 2,000 drivers who saved a total of $796,000. On average, they saved $398 each.

When we consider those people (or cases) that didn’t survive the threshold, the numbers change dramatically. You might hear an investment company say, “Investors who have stayed with us for ten years, made an average of 7.3% per year.” The threshold is stayed with us for ten years. Your question should be, “Well, what about those who didn’t stay for ten years?”

The survivorship fallacy doesn’t just affect numbers; it also affects qualities. Let’s say a prominent management journal publishes an article that proclaims, “The Ten Most Innovative Companies In The World Do These Three Things.” The threshold for selection is the ten most innovative companies (however that is measured). It’s quite possible that many other companies do the same three things but aren’t nearly as innovative. Since they didn’t survive the selection criterion, however, we don’t consider them.

What’s the moral? When you see an ad, put your critical thinking cap on. You’re going to need it.

Critical Thinking — Ripped From The Headlines!

Daniel Kahneman, the psychologist who won the Nobel prize in economics, reminds us that, “What you see is not all there is.” I thought about Kahneman when I saw the videos and coverage of the teenagers wearing MAGA hats surrounding, and apparently mocking, a Native American activist who was singing a tribal song during a march in Washington, D.C.

The media coverage essentially came in two waves. The first wave concluded that the teenagers were mocking, harassing, and threatening the activist. Here are some headlines from the first wave:

ABC News: “Viral video of Catholic school teens in ‘MAGA’ caps taunting Native Americans draws widespread condemnation; prompts a school investigation.”

Time Magazine: “Kentucky Teens Wearing ‘MAGA’ Hats Taunt Indigenous Peoples March Participants In Viral Video.”

Evening Standard (UK): “Outrage as teens in MAGA hats ‘mock’ Native American Vietnam War veteran.”

The second media wave provided a more nuanced view. Here are some more recent headlines:

New York Times: “Fuller Picture Emerges of Viral Video of Native American Man and Catholic Students.”

The Guardian (UK): “New video sheds more light on students’ confrontation with Native American.”

The Stranger: “I Thought the MAGA Boys Were S**t-Eating Monsters. Then I Watched the Full Video.”

So, who is right and who is wrong? I’m not sure that we can draw any certain conclusions. I certainly do have some opinions but they are all based on very short video clips that are taken out of context.

What lessons can we draw from this? Here are a few:

- Reality is complicated and — even in the best circumstances — we only see a piece of it.

- We see what we expect to see. Tell me how you voted, and I can guess what you saw.

- It’s very hard to draw firm conclusions from a brief slice-of-time sources such as a photograph or a video clip. The Atlantic magazine has an in-depth story about how this story evolved. One key sentence: “Photos by definition capture instants of time, and remove them from the surrounding flow.”

- There’s an old saying that “Journalism is the first draft of history”. Photojournalism is probably the first draft of the first draft. It’s often useful to wait to see how the story evolves. Slowing down a decision process usually results in a better decision.

- It’s hard to read motives from a picture.

- Remember that what we see is not all there is. As the Heath brothers write in their book, Decisive, move your spotlight around to avoid narrow framing.

- Humans don’t like to be uncertain. We like to connect the dots and explain things even when we don’t have all the facts. But, sometimes, uncertainty is the best we can hope for. When you’re uncertain, remember the lessons of Appreciative Inquiry and don’t default to the negative.

That’s Irrelevant!

In her book, Critical Thinking: An Appeal To Reason, Peg Tittle has an interesting and useful way of organizing 15 logical fallacies. Simply put, they’re all irrelevant to the assessment of whether an argument is true or not. Using Tittle’s guidelines, we can quickly sort out what we need to pay attention to and what we can safely ignore.

In her book, Critical Thinking: An Appeal To Reason, Peg Tittle has an interesting and useful way of organizing 15 logical fallacies. Simply put, they’re all irrelevant to the assessment of whether an argument is true or not. Using Tittle’s guidelines, we can quickly sort out what we need to pay attention to and what we can safely ignore.

Though these fallacies are irrelevant to truth, they are very relevant to persuasion. Critical thinking is about discovering the truth; it’s about the present and the past. Persuasion is about the future, where truth has yet to be established. Critical thinking helps us decide what we can be certain of. Persuasion helps us make good choices when we’re uncertain. Critical thinking is about truth; persuasion is about choice. What’s poison to one is often catnip to the other.

With that thought in mind, let’s take a look at Tittle’s 15 irrelevant fallacies. If someone tosses one of these at you in a debate, your response is simple: “That’s irrelevant.”

- Ad hominem: character– the person who created the argument is evil; therefore the argument is unacceptable. (Or the reverse).

- Ad hominem: tu quoque– the person making the argument doesn’t practice what she preaches. You say, it’s wrong to hunt but you eat meat.

- Ad hominem: poisoning the well— the person making the argument has something to gain. He’s not disinterested. Before you listen to my opponent, I would like to remind you that he stands to profit handsomely if you approve this proposal.

- Genetic fallacy– considering the origin, not the argument. The idea came to you in a dream. That’s not acceptable.

- Inappropriate standard: authority– An authority may claim to be an expert but experts are biased in predictable ways.

- Inappropriate standard: tradition – we accept something because we have traditionally accepted it. But traditions are often fabricated.

- Inappropriate standard: common practice – just because everybody’s doing it doesn’t make it true. Appeals to inertia and status quo.Example: most people peel bananas from the “wrong” end.

- Inappropriate standard: moderation/extreme – claims that an argument is true (or false) because it is too extreme (or too moderate). AKA the Fallacy of the Golden Mean.

- Appeal to popularity: bandwagon effect– just because an idea is popular doesn’t make it true. Often found in ads.

- Appeal to popularity: elites – only a few can make the grade or be admitted. Many are called; few are chosen.

- Two wrongs –our competitors have cheated, therefore, it’s acceptable for us to cheat.

- Going off topic: straw man or paper tiger– misrepresenting the other side. Responding to an argument that is not the argument presented.

- Going off topic: red herring – a false scent that leads the argument astray. Person 1: We shouldn’t do that. Person 2: If we don’t do it, someone else will.

- Going off topic: non sequitir – making a statement that doesn’t follow logically from its antecedents. Person 1: We should feed the poor. Person 2: You’re a communist.

- Appeals to emotion– incorporating emotions to assess truth rather than using logic. You say we should kill millions of chickens to stop the avian flu. That’s disgusting.

Chances are that you’ve used some of these fallacies in a debate or argument. Indeed, you may have convinced someone to choose X rather than Y using them. Though these fallacies may be persuasive, it’s useful to remember that they have nothing to do with truth.

One-Day Seminars – Fall 2018

This fall, in addition to my regular academic courses, I’ll teach three one-day seminars designed for managers and executives.

These seminars draw on my academic courses and are repackaged for professionals who want to think more clearly and persuade more effectively. They also provide continuing education credits under the auspices of the University of Denver’s Center for Professional Development.

If you’re guiding your organization into an uncertain future, you’ll find them helpful. Here are the dates and titles along with links to the registration pages.

- Saturday, September 29: Critical Thinking: How To Make Better Decisions (and Avoid Stupid Mistakes)

- Saturday, October 20: Innovation: How To Create Ideas That Generate Positive Results

- Saturday, November 10: Persuasion: How To Gain Agreement and Create Successful Teams

I hope to see you in one or more of these seminars. If you’re not in the Denver area, I can also take these on the road. Just let me know of your interest.

Why Study Critical Thinking?

People often ask me why they should take a class in critical thinking. Their typical refrain is, “I already know how to think.” I find that the best answer is a story about the mistakes we often make.

So I offer up the following example, drawn from recent news, about very smart people who missed a critical clue because they were not thinking critically.

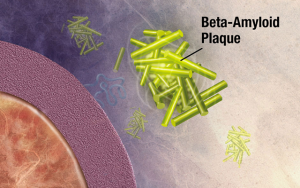

The story is about the conventional wisdom surrounding Alzheimer’s. We’ve known for years that people who have Alzheimer’s also have higher than normal deposits of beta amyloid plaques in their brains. These plaques build up over time and interfere with memory and cognitive processes.

The conventional wisdom holds that beta amyloid plaques are an aberration. The brain has essentially gone haywire and starts to attack itself. It’s a mistake. A key research question has been: how do we prevent this mistake from happening? It’s a difficult question to answer because we have no idea what triggered the mistake.

But recent research, led by Rudolph Tanzi and Robert Moir, considers the opposite question. What if the buildup of beta amyloid plaques is not a mistake? What if it serves some useful purpose? (Click here and here for background articles).

Pursuing this line of reasoning, Tanzi and Moir discovered the beta amyloid is actually an antimicrobial substance. It has a beneficial purpose: to attack bacteria and viruses and smother them. It’s not a mistake; it’s a defense mechanism.

Other Alzheimer’s researchers have described themselves as “gobsmacked” and “surprised” by the discovery. One said, “I never thought about it as a possibility.”

A student of critical thinking might ask, Why didn’t they think about this sooner? A key tenet of critical thinking is that one should always ask the opposite question. If conventional wisdom holds that X is true, a critical thinker would automatically ask, Is it possible that the opposite of X is true in some way?

Asking the opposite question is a simple way to identify, clarify, and check our assumptions. When the conventional wisdom is correct, it leads to a dead end. But, occasionally, asking the opposite question can lead to a Nobel Prize. Consider the case of Barry Marshall.

A doctor in Perth, Australia, Marshall was concerned about his patients’ stomach ulcers. Conventional wisdom held that bacteria couldn’t possibly live in the gastric juices of the human gut. So bacteria couldn’t possibly cause ulcers. More likely, stress and anxiety were the culprits. But Marshall asked the opposite question and discovered the bacteria now known a H. Pylori. Stress doesn’t cause ulcer, bacteria do. For asking the opposite question — and answering it — Marshall won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2005.

The discipline of critical thinking gives us a structure and method – almost a checklist – for how to think through complex problems. We should always ask the opposite question. We should be aware of common fallacies and cognitive biases. We should understand the basics of logic and argumentation. We should ask simple, blunt questions. We should check our egos at the door. If we do all this – and more – we tilt the odds in our favor. We prepare our minds systematically and open them to new possibilities – perhaps even the possibility of curing Alzheimer’s. That’s a good reason to study critical thinking.