Why Study Critical Thinking?

People often ask me why they should take a class in critical thinking. Their typical refrain is, “I already know how to think.” I find that the best answer is a story about the mistakes we often make.

So I offer up the following example, drawn from recent news, about very smart people who missed a critical clue because they were not thinking critically.

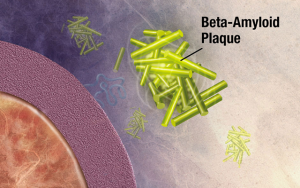

The story is about the conventional wisdom surrounding Alzheimer’s. We’ve known for years that people who have Alzheimer’s also have higher than normal deposits of beta amyloid plaques in their brains. These plaques build up over time and interfere with memory and cognitive processes.

The conventional wisdom holds that beta amyloid plaques are an aberration. The brain has essentially gone haywire and starts to attack itself. It’s a mistake. A key research question has been: how do we prevent this mistake from happening? It’s a difficult question to answer because we have no idea what triggered the mistake.

But recent research, led by Rudolph Tanzi and Robert Moir, considers the opposite question. What if the buildup of beta amyloid plaques is not a mistake? What if it serves some useful purpose? (Click here and here for background articles).

Pursuing this line of reasoning, Tanzi and Moir discovered the beta amyloid is actually an antimicrobial substance. It has a beneficial purpose: to attack bacteria and viruses and smother them. It’s not a mistake; it’s a defense mechanism.

Other Alzheimer’s researchers have described themselves as “gobsmacked” and “surprised” by the discovery. One said, “I never thought about it as a possibility.”

A student of critical thinking might ask, Why didn’t they think about this sooner? A key tenet of critical thinking is that one should always ask the opposite question. If conventional wisdom holds that X is true, a critical thinker would automatically ask, Is it possible that the opposite of X is true in some way?

Asking the opposite question is a simple way to identify, clarify, and check our assumptions. When the conventional wisdom is correct, it leads to a dead end. But, occasionally, asking the opposite question can lead to a Nobel Prize. Consider the case of Barry Marshall.

A doctor in Perth, Australia, Marshall was concerned about his patients’ stomach ulcers. Conventional wisdom held that bacteria couldn’t possibly live in the gastric juices of the human gut. So bacteria couldn’t possibly cause ulcers. More likely, stress and anxiety were the culprits. But Marshall asked the opposite question and discovered the bacteria now known a H. Pylori. Stress doesn’t cause ulcer, bacteria do. For asking the opposite question — and answering it — Marshall won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2005.

The discipline of critical thinking gives us a structure and method – almost a checklist – for how to think through complex problems. We should always ask the opposite question. We should be aware of common fallacies and cognitive biases. We should understand the basics of logic and argumentation. We should ask simple, blunt questions. We should check our egos at the door. If we do all this – and more – we tilt the odds in our favor. We prepare our minds systematically and open them to new possibilities – perhaps even the possibility of curing Alzheimer’s. That’s a good reason to study critical thinking.