A No Nonsense Guide to NFTs

Nonfungible tokens (NFTs) are all the rage these days. People are paying millions for NFTs that exist mainly as bits and pieces of computer code. At times like these, it’s useful to keep Gartner Group’s Hype Cycle in mind. A new idea is being hyped. Is it all smoke? Or is there some fire beneath it?

Nonfungible tokens (NFTs) are all the rage these days. People are paying millions for NFTs that exist mainly as bits and pieces of computer code. At times like these, it’s useful to keep Gartner Group’s Hype Cycle in mind. A new idea is being hyped. Is it all smoke? Or is there some fire beneath it?

Without being overly technical, let’s look at the attributes of any item (token/document/image/currency, etc.) stored in a blockchain. Here’s what you get:

- It’s indelibly time-stamped – anyone, anywhere in the world can verify exactly when the item was added to the blockchain. It follows that the item (whatever it is) must have been created before that date.

- It’s unmodifiable – when we write checks, we use ink because it can’t be modified. The blockchain brings the same benefit to digital items.

- It can’t be eradicated – nobody can destroy an item stored in the blockchain.

- There’s only one original – you can make copies, but the original is the real deal. And the original is easy to identify.

- Any transaction involving the item (a sale, for instance) will similarly be time-stamped, unmodifiable, and ineradicable.

What kinds of items would benefit from these attributes? Here are some categories:

- Legal documents – any document stored on the blockchain is essentially inviolable. We know its entire history and anything/everything that’s been done to it. I can foresee a future where only blockchain-stored documents will be legally enforceable. Indeed, I think I’ll store my will as an NFT so there can be no debate amongst my heirs as to what my intentions are.

- Ownership records – property records can result in unending discord if there’s any doubt about their veracity. For instance, if land ownership records disappear, how do we decide who has the right to use the land? The Peruvian economist, Hernando de Soto, suggests that land titles and deeds should be stored in a blockchain to preserve their integrity.

- Idea precedence – the entire scientific establishment is driven by idea precedence. Who made the discovery first? Who can claim credit for creating a new idea? Millions of dollars in royalties and patent rights can ride on date stamps. Blockchain dates are easily verified and inalterable.

- Artwork – a newly discovered Van Gogh painting recently sold for $19 million. Yet I can buy a nice poster of the same artwork for roughly $20. We all know that the original is worth much, much more than a copy. Yet how do we know if a digital item is an original? The blockchain knows. Indeed, this is the use case for the current NFT mania – it differentiates the digital original from digital copies.

- Provenance – where did the item come from? Whose hands did it pass through? Was it stolen or did it come to market legitimately? Dealers in historical artifacts wrestle with these questions every day. A token on the blockchain can record not only the item itself but also everything that has happened to the item over time.

Ultimately, the blockchain is about trust. Do we trust paper documents to accurately record who owns a piece of land? Or whether Scientist X created an idea before Scientist Y? Or whether an artwork can legally be sold? Once the hype settles down, I think the true value of the blockchain is that it can help us verify facts, enforce legal rights, and establish a climate of trust. That’s not hype.

Scanning The Future From Singapore

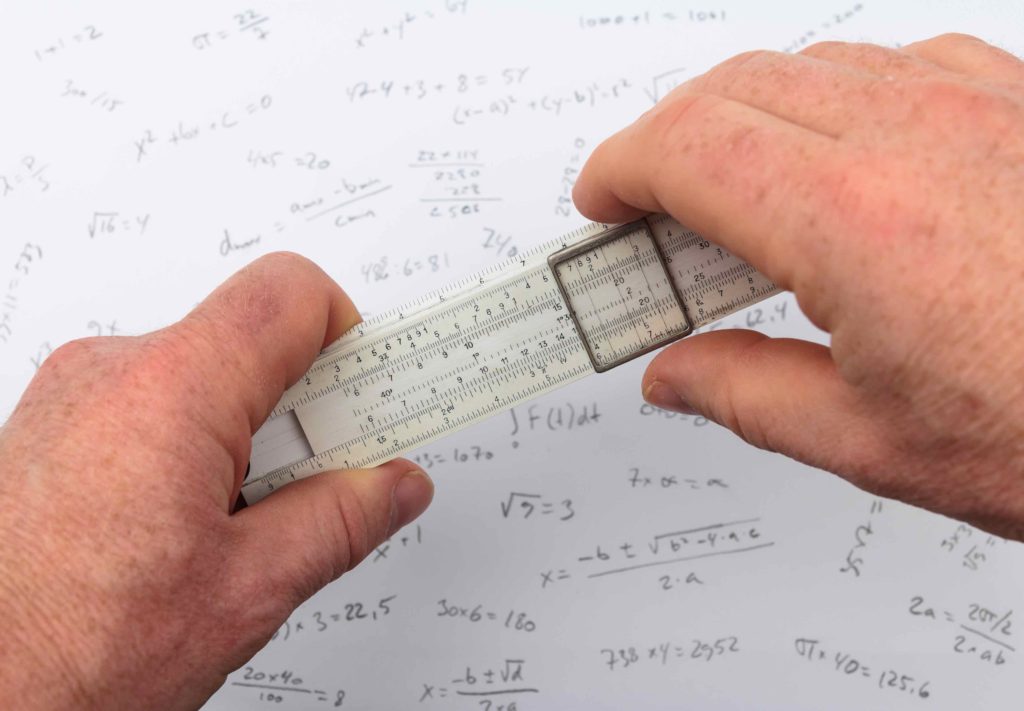

Can you use a slide rule? The ability to use one effectively could become an important status symbol in the future.

That’s just one idea that I plucked (with a little extrapolation) from Foresight, the biennial scan-the-horizon publication from Singapore’ s Center for Strategic Futures (CSF). Singapore, of course., is a very small country buffeted by giants. CSF describes the country as a “price-taker” – it must accept prices set by other market players.

So how will Singapore survive? That’s the basic question that CSF aims to answer in a series of symposia, structured thought processes, debates, stories, suggestions, conferences, nudges, and “sandboxes”. The idea is to keep ideas about the future top of mind among Singaporean leaders. As CSF says, “Nobody can predict the future, but we can be less surprised by it.”

Since 2012, CSF has published a Foresight document every other year. (Click here for the complete collection). The 2019 edition was published on July 1 and makes for fascinating reading.

CSF uses a structured process based on scenario planning to scan the horizon and create ideas about the future. (For some background on scenario planning, click here, here, and here). CSF calls its approach Scenario Planning Plus, which “retains Scenario Planning as its core, but taps on a broader suite of tools more suitable for the analysis of weak signals, and thinking about black swans and wild cards.” Scenario Planning Plus has six key purposes:

- Defining focus – is the problem simple, complicated, complex, chaotic, or disorderly? (See the Cynefin Problem Framework Definition).

- Environmental Scanning – identify critical emerging issues.

- Sense making – “… piece together a comprehensive and comprehensible picture of an issue.” CSF develops Driving Force Cards to stimulate creative discussions about these issues. (Click here for the current set).

- Develop possible futures – tell stories about what we do, think, and worry about in the future.

- Design strategies – given the various possibilities, how can we best respond to the future?

- Monitor – keep track of indicators, forward signals, and strategies to understand what’s happening and why. (Reading all of CSF’s Foresight documents gives a sense of how our perceptions have changed in just ten short years).

I encourage you to read through the Foresight document and to print out the Driving Force Cards to use in your planning sessions. They’ll stimulate your thinking in both practical and unexpected ways. To give you a sense of what the Foresight document contains, here are some ideas that I found especially interesting:

- Time banking – a marketplace where we exchange time instead of money. Such a marketplace might help us use our time more wisely.

- Heatstroke vaccinations – what if we can’t stop global warming? Maybe we could enhance humans to live in a warmer world. A vaccine against heatstroke would be a good start.

- Cobots – will robots replace humans in most production processes? Or will a combination of humans and robots – cobots – be a better solution?

And why might using a slide rule become a status symbol? When everything goes digital, being able to use analog devices could become a mark of distinction. We already see audiophiles abandoning digital recordings and returning to analog wax discs. Why not slide rules, too?

Can Zara Stop Globalization?

For several decades, I’ve assumed that globalization is more-or-less inevitable. As communication and transportation costs decline, manufacturers find it ever easier to take advantage of lower labor costs in developing countries (a process known as labor arbitrage). But recent developments may result in a new phenomenon, often described as glocalization – a worldwide trend toward local production and consumption. Three trends stand out as especially important: fast fashion, changing labor content, and the rise of a global middle class.

Fast is fashionable – based in Galicia, Spain, Zara SA pioneered the concept of fast fashion. The idea is simple – take newly spotted fashion trends from concept to deliverable in a matter of days, rather than weeks or months. Most apparel retailers introduce four to six clothing collections per year. Zara introduces as many as 20. Such speed has propelled Inditex, the group that owns Zara, to the “world’s largest apparel retailer”.

To move quickly, Zara and other fast fashion retailers, have to shrink their supply chains. They can’t wait weeks for shipments from faraway suppliers. The retailers have come to depend on local – or even hyperlocal – suppliers.

What’s next in fast fashion? Clothing-as-a-service. Most of my readers are not clothes horses, but we all have items in our closest that we will never wear again. So, why buy when you can rent? Rent The Runway is a subscription fashion service that will happily send you the latest fashions to use for a few days. Rent The Runway is even faster than Zara and even more dependent on hyperlocal suppliers.

By themselves, Zara and Rent The Runway won’t change our global supply chains. But other manufacturers are likely to adopt their business models. The “as-a-service” model is especially attractive. Uber and Lyft provide transportation as a service. Quip provides toothbrushing as a service. Salesforce provides software as a service. Google provides email as a service. And let’s not forget that libraries provide books as a service. As the “as-a-service” model proliferates, we’ll own less and use shorter, more localized supply chains.

Changing Labor Content – labor arbitrage works best under two conditions: 1) different countries – those that supply manufactured goods and those that consume them – have widely different pay scales; 2) the item being manufactured requires a lot of labor. The second variable – labor content – has been shrinking rapidly as factory automation proliferates. Today, a fully automated factory in say, Viet Nam is not appreciably cheaper than a similar factory in say, Nebraska. Moving production offshore is less appealing when the bulk of the value in a manufactured item comes from services other than labor.

Changing labor content affects services as well as goods. Many companies, for instance, have offshored their customer call centers to take advantage of lower labor costs in other countries. But artificial intelligence and improved voice recognition may soon change the economics of such decisions. When we can talk to a robot without realizing it (which will happen soon), it makes more sense to staff call centers with robots than with low-wage foreign workers.

The Rising Global Middle Class – recent estimates suggest that some 42% of the world’s population – roughly 3.2 billion people – are now in the middle class. Global poverty is shrinking, and global buying power is increasing. This does two things: First, the wage differential between developing and developed countries is shrinking rapidly. This shifts the first variable in the labor arbitrage equation. Second, and more subtly, it shifts the demand location. More people in developing countries can now afford to buy locally produced goods and services. Rather than shipping goods overseas, local manufacturers now have a growing local market for their products.

As McKinsey and Co. point out, this trend reduces trade intensity – the proportion of goods that are produced in one country and sold in another. In 2007, for instance, China exported 17% of what it produced. By 2017, this figure declined to 9%.

What’s it all mean? Perhaps it means that our nascent trade wars are not necessary. Populist governments are trying to stop globalization through tariffs and other punitive measures. The tools are crude and outcomes uncertain. But the problem they’re trying to solve has already morphed into something different. Rather than solving yesterday’s problem through political means, it may well be better to just let the market trends play out.

The goal now is to take advantage of glocalization rather than to stop globalization. Trade intensity and labor arbitrage are both falling. We’re moving toward shorter rather than longer supply chains. Exports of manufactured goods are growing in absolute terms but shrinking relative to service exports and local consumption. We may see some decoupling of established international supply chains. Is glocalization good news? In many ways it is. The shift from global to local production will probably create local jobs and even greater personalization. As always, there are risks as well. Ed Luce, writing in the Financial Times, quotes an old saying, “When countries stop trading goods, they start trading blows.”

Whom Do You Trust? America or Facebook?

The promise of cryptocurrencies is that we can create a widely-acceptable medium of exchange without having to trust anyone. Cryptocurrencies have no central authority, no government agency to vouch for them. We don’t need to trust a government or a bank or a stock exchange. Elites can’t cheapen our currency because no elites are involved. Indeed, no one is involved. The currency is distributed across multiple computers and multiple networks. To manipulate the currency, one would need to control all the computers in the world – a seemingly impossible task.

In the original conception, the value of a cryptocurrency is based on nothing more than supply-and demand. Value is not linked to any physical asset like gold or oil or even paper currencies like dollars. Since there is no asset behind the currency, no one can manipulate the value of the currency by manipulating the underlying asset. Rather than trusting a government or an agency or a bank, we place our trust in an algorithm distributed around the world.

(The distributed nature of cryptocurrencies also makes them quite slow. Speeding up transactions is a major challenge for blockchain researchers. The most promising solution seems to be “sharding” – a technology worth keeping an eye on.)

Traditionally, we’ve trusted governments to create and maintain the value of national currencies. That’s been a pretty good bet in the United States, less so in Venezuela. But, really, do we need a nation to create a widely acceptable currency? Cryptocurrencies suggest that the answer is “no”.

But there’s a not-so-subtle problem with cryptocurrencies. The elephant in the room is that many people (myself included) view cryptocurrencies as a new version of the Wild West – a territory populated by libertarians, wild-eyed visionaries, snake oil salesmen, drug dealers, scam artists, and terrorists. And, by the way, some person created the algorithm and could potentially manipulate it for illicit purposes. Simply put, the current cryptocurrency scene does not inspire trust.

To fill the trust gap, several “trusted” agencies have stepped forward to offer cryptocurrencies based on a trusted brand and/or on physical assets. Case in point: J.P. Morgan Chase’s “JPM Coin”. Announced earlier this year, (click here, here, and here) JPM Coin is backed by a major bank and based on a physical asset: the U.S. dollar. The company touts JPM Coin as a simpler, faster way to make and clear payments.

This past week, of course, another “trusted” organization – Facebook – announced that it will introduce a new digital currency called Libra next year. (Click here and here). Facebook wraps its announcement in humanitarian gauze – it’s simply providing an effective payment service to the world’s unbanked citizens. As Evgeny Morozov points out, however, Facebook is actually doing two things:

- Preparing to take on China’s social media giants, Tencent and Alibaba, which already combine payments and communications.

- Positioning itself as a “as a rebel force against mediocre bureaucrats and sluggish corporate incumbents”. It’s doing battle against a coalition of lazy, inept, corrupt – untrustworthy – bankers, bureaucrats, and politicians. Morozov suggests that Facebook is activating its populist supporters to keep regulators at bay. More broadly, it’s a “plan to break the global financial system.”

Could Facebook’s Libra actually become a global currency at the expense of the dollar, yen, Euro, and renminbi? Facebook currently has 2.38 billion active users. That number makes even China’s population look small. If a significant portion choose the Libra over existing currencies, then the money we know today could become irrelevant. If a nation’s currency is irrelevant, how relevant is the government?

Given all this, here’s a basic question — whom do you trust more: 1) the American government; or 2) Facebook?

(Note that JPM Coin and Libra are not truly cryptocurrencies, at least not in the original sense of the word. A cryptocurrency has three elements: 1) No central authority, agency, governing body or processor. Clearly J.P. Morgan and Facebook are centralized governing bodies. 2) No physical assets backing the currency. JPM Coin, uses the U.S dollar as its backing asset – it’s a digital currency based on a fiat currency. Facebook says that Libra will be based on physical assets, though it hasn’t quite defined them. 3) Permissionless – you don’t have to ask anyone’s permission to use a cryptocurrency. To use JPM Coin, you need to have an account at J.P. Morgan. To use Libra, you’ll need a Facebook account. Given this, it’s probably best to call JPM Coin and Libra “digital currencies” as opposed to “cryptocurrencies”.)

What’s Walking Good For?

I often ask my students a simple question: What were you doing the last time you had a good idea? Whatever they answer, I say: “Do more of that and you’ll have more good ideas.”

So what are they doing when they have good ideas? A fair number – often a majority – are walking. Taking a break and going for a walk stimulates our thinking in ways that produce interesting and novel ideas. Walking takes a minimum amount of conscious effort; we have plenty of mental bandwidth left for other interesting thoughts. Walking also provides a certain amount of stimulation. The sights and sounds and smells trigger memories and images that we can combine in novel ways. By moving our bodies slowly, we create thoughts that move much more quickly.

Going for a walk with a friend, colleague, or loved one can also help us create richer, deeper conversations. Walking stimulates novel thoughts; if a companion is beside us, we can share those thoughts immediately. The back-and-forth can lead us into new territory. A good conversation is not just an exchange of existing ideas. Rather, it produces new ideas – and walking can help.

Walking can also help us have difficult conversations. The key here may be our posture and proximity rather than walking per se. When we walk with another person, we are typically side-by-side, not face-to-face. We’re not confronting each other physically. We’re talking to the air, rather than at each other. We’re slightly insulated from each other, which makes it easier to both make and receive blunt statements.

According to Walk-And-Talk therapists like Kate Hays, walking can also enhance traditional psychotherapy sessions. Walking with a therapist “…spurs creative, deeper ways of thinking often released by mood improving physical activity.” Walking seems especially helpful when the conversation is between a parent and, say, a teenager. We feel close, but not intimidated. (Side note: we often describe deep conversations as “heart-to-heart” but rarely describe them as “face-to-face.”)

What else can walking do? It’s an “active fingerprint.” As the MIT Technology Review puts it, “… your gait [is} a very individual and hard-to-imitate trait.” In other words, the way you walk uniquely identifies you.

Clearly, we can use gait-based identification for positive or negative ends. With so many security cameras in place today, we’re rightly concerned about facial recognition as an invasion of privacy. But we can hide our faces with something as simple as a surgical mask. Disguising the way we walk is much more difficult.

On the other hand, think of a device – perhaps a smart phone – that can uniquely identify you based solely on your gait. You put your phone in your pocket and walk along; it “knows” who you are. Rather than depending on fingerprints or passwords, the device simply monitors your gait. One benefit is convenience – you don’t have to enter a password every time you want to use the device. The second benefit is perhaps more important: security. A thief could steal your password or even an image of your fingerprint. But could they imitate your gait? Probably not.

What else is walking good for? Oh, simple things like health, flexibility, weight loss, mental acuity, sociability, and so on. I’d like to hear your stories about the benefits of walking. Just send me an e-mail. I’ll read them after I get back from my walk.