Critical Thinking — Ripped From The Headlines!

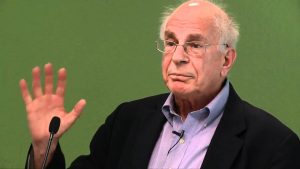

Daniel Kahneman, the psychologist who won the Nobel prize in economics, reminds us that, “What you see is not all there is.” I thought about Kahneman when I saw the videos and coverage of the teenagers wearing MAGA hats surrounding, and apparently mocking, a Native American activist who was singing a tribal song during a march in Washington, D.C.

The media coverage essentially came in two waves. The first wave concluded that the teenagers were mocking, harassing, and threatening the activist. Here are some headlines from the first wave:

ABC News: “Viral video of Catholic school teens in ‘MAGA’ caps taunting Native Americans draws widespread condemnation; prompts a school investigation.”

Time Magazine: “Kentucky Teens Wearing ‘MAGA’ Hats Taunt Indigenous Peoples March Participants In Viral Video.”

Evening Standard (UK): “Outrage as teens in MAGA hats ‘mock’ Native American Vietnam War veteran.”

The second media wave provided a more nuanced view. Here are some more recent headlines:

New York Times: “Fuller Picture Emerges of Viral Video of Native American Man and Catholic Students.”

The Guardian (UK): “New video sheds more light on students’ confrontation with Native American.”

The Stranger: “I Thought the MAGA Boys Were S**t-Eating Monsters. Then I Watched the Full Video.”

So, who is right and who is wrong? I’m not sure that we can draw any certain conclusions. I certainly do have some opinions but they are all based on very short video clips that are taken out of context.

What lessons can we draw from this? Here are a few:

- Reality is complicated and — even in the best circumstances — we only see a piece of it.

- We see what we expect to see. Tell me how you voted, and I can guess what you saw.

- It’s very hard to draw firm conclusions from a brief slice-of-time sources such as a photograph or a video clip. The Atlantic magazine has an in-depth story about how this story evolved. One key sentence: “Photos by definition capture instants of time, and remove them from the surrounding flow.”

- There’s an old saying that “Journalism is the first draft of history”. Photojournalism is probably the first draft of the first draft. It’s often useful to wait to see how the story evolves. Slowing down a decision process usually results in a better decision.

- It’s hard to read motives from a picture.

- Remember that what we see is not all there is. As the Heath brothers write in their book, Decisive, move your spotlight around to avoid narrow framing.

- Humans don’t like to be uncertain. We like to connect the dots and explain things even when we don’t have all the facts. But, sometimes, uncertainty is the best we can hope for. When you’re uncertain, remember the lessons of Appreciative Inquiry and don’t default to the negative.

Delayed Intuition – How To Hire Better

Daniel Kahneman is rightly respected for discovering and documenting any number of irrational human behaviors. Prospect theory – developed by Kahneman and his colleague, Amos Tversky – has led to profound new insights in how we think, behave, and spend our money. Indeed, there’s a straight line from Kahneman and Tversky to the new discipline called Behavioral Economics.

In my humble opinion, however, one of Kahneman’s innovations has been overlooked. The innovation doesn’t have an agreed-upon name so I’m proposing that we call it the Kahneman Interview Technique or KIT.

The idea behind KIT is fairly simple. We all know about the confirmation bias – the tendency to attend to information that confirms what we already believe and to ignore information that doesn’t. Kahneman’s insight is that confirmation bias distorts job interviews.

Here’s how it works. When we meet a candidate for a job, we immediately form an impression. The distortion occurs because this first impression colors the rest of the interview. Our intuition might tell us, for instance, that the candidate is action-oriented. For the rest of the interview, we attend to clues that confirm this intuition and ignore those that don’t. Ultimately, we base our evaluation on our initial impressions and intuition, which may be sketchy at best. The result – as Google found – is that there is no relationship between an interviewer’s evaluation and a candidate’s actual performance.

To remove the distortion of our confirmation bias, KIT asks us to delay our intuition. How can we delay intuition? By focusing first on facts and figures. For any job, there are prerequisites for success that we can measure by asking factual questions. For instance, a salesperson might need to be: 1) well spoken; 2) observant; 3) technically proficient, and so on. An executive might need to be: 1) a critical thinker; 2) a good strategist; 3) a good talent finder, etc.

Before the interview, we prepare factual questions that probe these prerequisites. We begin the interview with facts and develop a score for each prerequisite – typically on a simple scale like 1 – 5. The idea is not to record what the interviewer thinks but rather to record what the candidate has actually done. This portion of the interview is based on facts, not perceptions.

Once we have a score for each dimension, we can take the interview in more qualitative directions. We can ask broader questions about the candidate’s worldview and philosophy. We can invite our intuition to enter the process. At the end of the process, Kahneman suggests that the interviewer close her eyes, reflect for a moment, and answer the question, How well would this candidate do in this particular job?

Kahneman and other researchers have found that the factual scores are much better predictors of success than traditional interviews. Interestingly, the concluding global evaluation is also a strong predictor, especially when compared with “first impression” predictions. In other words, delayed intuition is better at predicting job success than immediate intuition. It’s a good idea to keep in mind the next time you hire someone.

I first learned about the Kahneman Interview Technique several years ago when I read Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast And Slow. But the book is filled with so many good ideas that I forgot about the interviews. I was reminded of them recently when I listened to the 100th episode of the podcast, Hidden Brain, which features an interview with Kahneman. This article draws on both sources.

Pre-Suasion: Influence Before Influence

In Tin Men, Richard Dreyfus and Danny De Vito play two salesmen locked in bitter competition as they sell aluminum siding to householders in Baltimore. The movie is somewhat forgettable, but it offers a master class in sales techniques.

In one scene, Dreyfus knocks on a prospective customer’s door while also dropping a five-dollar bill on the doormat. When the customer opens the door, Dreyfus picks up the bill and says, “Wow. I just found this on your doormat. It’s not mine. It must be yours.” Somewhat confused, the homeowner accepts the bill and invites Dreyfus inside where he makes a big sale.

Robert Cialdini would call Dreyfus’ maneuver a good example of pre-suasion. Before Dreyfus even introduces himself, he has already done something to show that he’s a stand-up guy. He has earned some trust.

Cialdini himself gained our trust in his first book, Influence, which details six “weapons of influence”: reciprocity, consistency, social proof, liking, authority, and scarcity. In his new book, Pre-Suasion, he invites us to look at what happens before we deploy our weapons.

Pre-suasion is not a new idea. It’s at least as old as the traditional advice: Do a favor before asking for a favor. Like Dreyfus, however, Cialdini seems like a stand-up guy so we go along for the read. It’s a good idea because the book is chock full of practical advice on how to set the stage for persuasion.

A key idea is the “attention chute”. When we focus our attention on something, we don’t see anything else. The opportunity cost of paying attention is inattentional blindness. Thus, we don’t consider other alternatives. If our attention is focused on globalization, we may not notice how many jobs are eliminated by automation.

As Cialdini points out, the attention chute makes us suckers for palm readers. A palm reader says, “Your palm suggests that you’re a very stubborn person. Is that true?” We focus on the idea of stubbornness and search our memory banks for examples. We don’t think about the opposite of stubbornness and we don’t search for examples of it. It’s almost certain that we can find some examples of stubbornness in our memories. How could the palm reader have possibly known?

The attention chute is also known as the focusing illusion. We believe that what we focus on is important, but it may just be an illusion. If we’re focused on it, it must be important, right? It’s a cognitive bias that a palm reader or aluminum siding salesman can easily manipulate.

What’s the best defense? It’s a good idea to keep Daniel Kahneman’s advice in mind: “Nothing in life is as important as you think it is, while you are thinking about it.” If the media is filled with horror stories about the Ebola virus, you’ll probably think it’s important. But really, it’s not nearly as important as you think it is while you’re thinking about it.

Cialdini takes the attention chute one step further with the idea that “what’s focal is causal.” We assume that what we focus on is not just important; it’s also the cause of whatever we’re focused on. As Cialdini notes, economists think that the exchange of money is the cause of many transactions. But maybe not. Maybe there’s another reason for the transaction. Maybe the money is just a side benefit, not the motivating cause.

The idea that focal-is-causal has many complications. For example, the first lots identified in the famous Tylenol cyanide attacks were numbers 2880 and 1910. The media broadcast the numbers far and wide and many of us used them to play the lottery. They must be important, right?

Focal-is-causal can also lead to false confessions. The police focus on a person of interest and convince themselves that she caused the crime. (This is also known as satisficing or temporizing). They then use all the tricks in the book to convince her of the same thing.

Cialdini is a good writer and has plenty of interesting stories to tell. If you like Daniel Kahneman or Dan Ariely or Jordan Ellenberg or the brothers Heath, you’ll like his book as well. And who knows? It may even help you beat the rap when the police are trying to get a confession out of you.

Reminiscence Bumps and Helicopter Parents

It’s the reminiscence bump.

If you ask someone over the age of thirty to tell you their life story, they’ll over-emphasize some portions and under-emphasize others. Most likely they’ll recall incidents in their late teens and early twenties much more vividly than other periods of their lives. What happens in our thirties stays in our thirties. What happens in our formative years stays with us forever.

It’s known as the reminiscence bump and social scientists have been researching it since the early 1980s. Activities and events that occur in late adolescence and early adulthood leave an indelible mark on our memories. As Katy Waldman puts it, …”there is something deeply, weirdly meaningful about this period.”

Nobody knows quite why the reminiscence bump occurs. Dan McAdams, writing in the Review of General Psychology, associates it with the formation of identity. As we enter adolescence, many different identities are available to us. We could become nerds. Or athletes. Or scholars. Or criminals (especially those with low heart rates). As McAdams points out, William James called this the “one-in-many-selves paradox”.

Yet we generally emerge from adolescence with one more-or-less integrated identity. We want that identity to be coherent. Indeed, there are multiple types of coherent, including biographical coherence, causal coherence, thematic coherence, and temporal coherence. McAdams surmises that integrating multiple potential stories into one coherent identity is a formative life experience that creates long lasting memories.

The articles I’ve read focus on what causes the reminiscence bump. I’m also interested in what the reminiscence bump causes. We believe that the bump is universal; we all have it. Does the fact that we remember our formative years better than other years affect our behavior in later life?

I’ve written previously about the availability bias. As Daniel Kahneman has pointed out, humans are not naturally good at statistics. We have difficulty answering questions dealing with probability. So we substitute a simpler question and answer it.

For instance, let’s say someone asks us, “How likely is it that someone will burglarize your house while you’re away for the weekend?” We have no idea what the probabilities are or even how to calculate them. So we answer a simpler question: “How easy is it for me to remember stories of friends’ houses being burglarized?” If it’s easy to remember such stories, we estimate that the probability is high. If it’s difficult, we estimate that the probability is low. (This is sometimes known as the vividness bias – vivid events are easy to recall from memory).

What events are easy for us to recall from our life histories? Compared to all other events, the reminiscence bump suggests that events from adolescence and early adulthood are easiest to recall. The availability bias suggests that we will overestimate the probability that similar events will happen in the future. We can recall them easily. Therefore, we assume they’re highly probable to recur.

Now, consider the adolescent brain. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, it’s “…still under construction.” We tend to engage in riskier behaviors in our teenage years because our executive function is not fully developed. As most of us can well remember, we do stupid things.

What do we disproportionately remember about our lives? The risky and thoughtless behaviors of our formative years. If the availability bias is correct, we will overestimate the probability that these same behaviors will occur again, perhaps in our children. Could this be the root cause of the helicopter parenting that we seem so worried about today? It’s a complicated question but it’s certainly worth a good research project.

I’m A Better Person In Spanish

Me llamo Travieso Blanco.

I speak Spanish reasonably well but I find it very tiring … which suggests that I probably think more clearly and ethically in Spanish than in English.

Like so many things, it’s all related to our two different modes of thinking: System1 and System 2. System 1 is fast and efficient and operates below the level of consciousness. It makes a great majority of our decisions, typically without any input from our conscious selves. We literally make decisions without knowing that we’re making decisions.

System 2 is all about conscious thought. We bring information into System 2, think it through, and make reasoned decisions. System 2 uses a lot of calories; it’s hard work. As Daniel Kahneman says, “Thinking is to humans as swimming is to cats; they can do it but they’d prefer not to.”

English, of course, is my native language. (American English, that is). It’s second nature to me. It’s easy and fluid. I can think in English without thinking about it. In other words, English is the language of my System 1. At this point in my life, it’s the only language in my System 1 and will probably remain so.

To speak Spanish, on the other hand, I have to invoke System 2. I have to think about my word choice, pronunciation, phrasing, and so on. It’s hard work and wears me out. I can do it but I would have to live in Spain for a while for it to become easy and fluid. (That’s not such a bad idea, is it?)

You may remember that System 1 makes decisions using heuristics or simple rules of thumb. System 1 simplifies everything and makes snap judgments. Most of the time, those judgments are pretty good but, when they’re wrong, they’re wrong in consistent ways. System 1, in other words, is the source of biases that we all have.

To overcome these biases, we have to bring the decision into System 2 and consider it rationally. That takes time, effort, and energy and, oftentimes, we don’t do it. It’s easy to conclude that someone is a jerk. It’s more difficult to invoke System 2 to imagine what that person’s life is like.

So how does language affect all this? I can only speak Spanish in my rational, logical, conscious System 2. When I’m thinking in Spanish, all my rational neurons are firing. I tend to think more carefully, more thoughtfully, and more ethically. It’s tiring.

When I think in English, on the other hand, I could invoke my System 2 but I certainly don’t have to. I can easily use heuristics in English but not in Spanish. I can jump to conclusions in English but not in Spanish.

The seminal article on this topic was published in 2012 by three professors from the University of Chicago. They write, “Would you make the same decisions in a foreign language as you would in your native tongue? It may be intuitive that people would make the same choices regardless of the language they are using…. We discovered, however, that the opposite is true: Using a foreign language reduces decision-making biases.”

So, it’s true: I’m a better person in Spanish.