Delayed Intuition – How To Hire Better

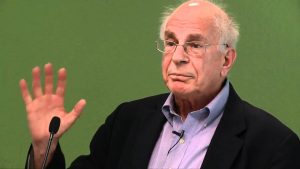

Daniel Kahneman is rightly respected for discovering and documenting any number of irrational human behaviors. Prospect theory – developed by Kahneman and his colleague, Amos Tversky – has led to profound new insights in how we think, behave, and spend our money. Indeed, there’s a straight line from Kahneman and Tversky to the new discipline called Behavioral Economics.

In my humble opinion, however, one of Kahneman’s innovations has been overlooked. The innovation doesn’t have an agreed-upon name so I’m proposing that we call it the Kahneman Interview Technique or KIT.

The idea behind KIT is fairly simple. We all know about the confirmation bias – the tendency to attend to information that confirms what we already believe and to ignore information that doesn’t. Kahneman’s insight is that confirmation bias distorts job interviews.

Here’s how it works. When we meet a candidate for a job, we immediately form an impression. The distortion occurs because this first impression colors the rest of the interview. Our intuition might tell us, for instance, that the candidate is action-oriented. For the rest of the interview, we attend to clues that confirm this intuition and ignore those that don’t. Ultimately, we base our evaluation on our initial impressions and intuition, which may be sketchy at best. The result – as Google found – is that there is no relationship between an interviewer’s evaluation and a candidate’s actual performance.

To remove the distortion of our confirmation bias, KIT asks us to delay our intuition. How can we delay intuition? By focusing first on facts and figures. For any job, there are prerequisites for success that we can measure by asking factual questions. For instance, a salesperson might need to be: 1) well spoken; 2) observant; 3) technically proficient, and so on. An executive might need to be: 1) a critical thinker; 2) a good strategist; 3) a good talent finder, etc.

Before the interview, we prepare factual questions that probe these prerequisites. We begin the interview with facts and develop a score for each prerequisite – typically on a simple scale like 1 – 5. The idea is not to record what the interviewer thinks but rather to record what the candidate has actually done. This portion of the interview is based on facts, not perceptions.

Once we have a score for each dimension, we can take the interview in more qualitative directions. We can ask broader questions about the candidate’s worldview and philosophy. We can invite our intuition to enter the process. At the end of the process, Kahneman suggests that the interviewer close her eyes, reflect for a moment, and answer the question, How well would this candidate do in this particular job?

Kahneman and other researchers have found that the factual scores are much better predictors of success than traditional interviews. Interestingly, the concluding global evaluation is also a strong predictor, especially when compared with “first impression” predictions. In other words, delayed intuition is better at predicting job success than immediate intuition. It’s a good idea to keep in mind the next time you hire someone.

I first learned about the Kahneman Interview Technique several years ago when I read Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast And Slow. But the book is filled with so many good ideas that I forgot about the interviews. I was reminded of them recently when I listened to the 100th episode of the podcast, Hidden Brain, which features an interview with Kahneman. This article draws on both sources.

Curmudgeons and Critical Thinking

My brain thinks it so it must be true.

I don’t consider myself a curmudgeon. But every now and then my System 1 takes off on a rant that is entirely irrational. It’s also subconscious so I don’t even know it’s happening.

My System 1 wants to create a continuous story of how I interact with the world. Sometimes the story unfolds rationally. I use solid evidence to create a story that flows logically from premise to conclusion.

Sometimes, however, there’s no solid evidence available. Does that stop my System 1 from concocting a story? Of course not. I simply make up a story out of whole cloth. The story may well be consistent in its internal details but may also be entirely fictional. I use it to satisfy my need for a comforting explanation of the world around me. In this regard, it’s no different from a child’s bedtime story.

Though I refer to it as System 1, it’s actually my left brain interpreter that does the work. According to Wikipedia, “…the left brain interpreter refers to the construction of explanations by the left brain in order to make sense of the world by reconciling new information with what was known before. … In reconciling the past and the present, the left brain interpreter may confer a sense of comfort to a person, by providing a feeling of consistency and continuity in the world. This may in turn produce feelings of security that the person knows how “things will turn out” in the future.”

Apparently, our desire for “feelings of security” is deep and strong. So strong, in fact, that our left brain interpreter may create a “contrived” story even in the absence of facts, data, and evidence. While the interpreter often interprets things logically, it “…may also enhance the opinion of a person about themselves and produce strong biases which prevent the person from seeing themselves in the light of reality.”

How often does the interpreter create completely contrived stories? More often than you might think. In fact, my left brain interpreter took off on a flight of fancy just the other day.

Suellen and I were driving to an event at the University of Denver. We were running a few minutes late. We were on a four-lane boulevard where the speed limit is 30 miles per hour. But most people drive at 40 mph because the road is broad and straight. We got stuck behind a Prius that was driving at precisely the speed limit. Here’s how my left brain interpreted the event:

Damn tree-hugger in a Prius! Thinks he’s superior to the rest of us because he’s saving the planet. He wants to keep the rest of us in line too, so he’s driving the speed limit to make sure that we behave ourselves. What a jerk! Who does he think he is? Doesn’t he know it’s rush hour? What gives him the right to drive slowly?

That’s a pretty good rant. But it has nothing to do with reality. I didn’t know anything about the driver but I still created a story to connect the dots. The story followed a simple arc: he’s a jerk and I’m an innocent victim. It’s simple. It’s internally consistent. It enhances my opinion about myself. And it’s completely fictional.

How did I know that I was ranting? Because I interrupted my own train of thought. When I thought about my thinking – and brought the story into my conscious mind – I realized it was ridiculous. It wasn’t his fault that I was running late. And who, after all, was trying to break the law? Not him but me.

I was certainly thinking like a curmudgeon. I suspect that we all do from time to time. I stopped being a curmudgeon only when I realized that I needed to think about my thinking. Curmudgeons may well think primarily with their left brain interpreter. Whatever story the interpreter concocts becomes their version of reality. They don’t think about their thinking.

When we’re with someone who is lost in thought, we might say, “A penny for your thoughts.” It’s a useful phrase that often starts a meaningful conversation. We might make it more useful by altering the wording. To avoid being a curmudgeon, we need to think about our thinking. Perhaps we should simply say, “A penny for my thoughts.”

Coincidence? I Think Not.

Coincidence? I think not.

It’s a tough world out there so I start every day by reading the comics in our local newspaper. Comics and caffeine are the perfect combination to get the day started.

In our paper, the comics are in the entertainment section, which is usually either eight or twelve pages long. The comics are at the back. Last week, I pulled the entertainment section out, glanced at the first page, then flipped it open to the comics.

While I was reading my favorite comics, a random thought popped into my head: “I wonder if I could use Steven Wright’s comedy to teach any useful lessons in my critical thinking class?” Pretty random, eh?

Do you know Steven Wright? He’s an amazingly gifted comedian whose popularity probably peaked in the nineties. Elliot was a kid at the time and he and I loved to listen to Wright’s tapes. (Suellen was a bit less enthusiastic). Here are some of his famous lines:

- All those who believe in psychokinesis raise my hand.

- I saw a man with wooden legs. And real feet.

- I almost had a psychic girlfriend but she left me before we met.

- Everyone has a photographic memory. Some just don’t have film.

Given Wright’s ironic paraprosdokians, it seems logical that I would think of him as a way to teach critical thinking. But why would he pop up one morning when I was enjoying my coffee and comics?

I finished the comics and closed the entertainment section. On the back page, I spotted an article announcing that Steven Wright was in town to play some local comedy clubs. I was initially dumbfounded. I hadn’t seen the article before reading the comics. How could I have known? I reached an obvious conclusion: I must have psychic powers.

While congratulating myself on my newfound powers, I turned back to the front page of the entertainment section. Then my crest fell. There, in the upper left hand corner of the front page, was a little blurb: “Steven Wright’s in town.”

I must have seen the blurb when I glanced at the front page. But it didn’t register consciously. I didn’t know that I knew it. Rather, my System 1 must have picked it up. Then, while reading the comics, System 1 passed a cryptic note to my System 2. I had been thinking about my critical thinking class. When my conscious mind got the Seven Wright cue from System 1, I coupled it with what I was already thinking.

I wasn’t psychic after all. Was it a coincidence? Not at all. Was I using ESP? Nope. It was just my System 1 taking me for a ride. Let that be a lesson to us all.

(For more on System 1 versus System 2, click here and here and here).

A Joke About Your Mind’s Eye

Here’s a cute little joke:

The receptionist at the doctor’s office goes running down the hallway and says, “Doctor, Doctor, there’s an invisible man in the waiting room.” The Doctor considers this information for a moment, pauses, and then says, “Tell him I can’t see him”.

It’s a cute play on a situation we’ve all faced at one time or another. We need to see a doctor but we don’t have an appointment and the doc just has no time to see us. We know how it feels. That’s part of the reason the joke is funny.

Now let’s talk about the movie playing in your head. Whenever we hear or read a story, we create a little movie in our heads to illustrate it. This is one of the reasons I like to read novels — I get to invent the pictures. I “know” what the scene should look like. When I read a line of dialogue, I imagine how the character would “sell” the line. The novel’s descriptions stimulate my internal movie-making machinery. (I often wonder what the interior movies of movie directors look like. Do Tim Burton’s internal movies look like his external movies? Wow.)

We create our internal movies without much thought. They’re good examples of our System 1 at work. The pictures arise based on our experiences and habits. We don’t inspect them for accuracy — that would be a System 2 task. (For more on our two thinking systems, click here). Though we don’t think much about the pictures, we may take action on them. If our pictures are inaccurate, our decisions are likely to be erroneous. Our internal movies could get us in trouble.

Consider the joke … and be honest. In the movie in your head, did you see the receptionist as a woman and the doctor as a man? Now go back and re-read the joke. I was careful not to give any gender clues. If you saw the receptionist as a woman and the doctor as a man (or vice-versa), it’s because of what you believe, not because of what I said. You’re reading into the situation and your interpretation may just be erroneous. Yet again, your System 1 is leading you astray.

What does this have to do with business? I’m convinced that many of our disagreements and misunderstandings in the business world stem from our pictures. Your pictures are different from mine. Diversity in an organization promotes innovation. But it also promotes what we might call “differential picture syndrome”.

So what to do? Simple. Ask people about the pictures in their heads. When you hear the term strategic reorganization, what pictures do you see in your mind’s eye? When you hear team-building exercise, what movie plays in your head? It’s a fairly simple and effective way to understand our conceptual differences and find common definitions for the terms we use. It’s simple. Just go to the movies together.

Librarian, Farmer, Debacle

In his book, Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman has an interesting example of a heuristic bias. Read the description, then answer the question.

Steve is very shy and withdrawn, invariably helpful but with little interest in people or in the world of reality. A meek and tidy soul, he has a need for order and structure, and a passion for detail.

Is Steve more likely to be a librarian or a farmer?

I used this example in my critical thinking class the other night. About two-thirds of the students guessed that Steve is a librarian; one-third said he’s a farmer. As we debated Steve’s profession, the class focused exclusively on the information in the simple description.

Kahneman’s example illustrates two problems with the rules of thumb (heuristics) that are often associated with our System 1 thinking. The first is simply stereotyping. The description fits our widely held stereotype of male librarians. It’s easy to conclude that Steve fits the stereotype. Therefore, he must be a librarian.

The second problem is more subtle — what evidence do we use to draw a conclusion? In the class, no one asked for additional information. (This is partially because I encouraged them to reach a decision quickly. They did what their teacher asked them to do. Not always a good idea.) Rather they used the information that was available. This is often known as the availability bias — we make a decision based on the information that’s readily available to us. As it happens, male farmers in the United States outnumber male librarians by a ratio of about 20 to 1. If my students had asked about this, they might have concluded that Steve is probably a farmer — statistically at least.

The availability bias can get you into big trouble in business. To illustrate, I’ll draw on an example (somewhat paraphrased) from Paul Nutt’s book, Why Decisions Fail.

Peca Products is locked in a fierce competitive battle with its archrival, Frangro Enterprises. Peca has lost 4% market share over the past three quarters. Frangro has added 4% in the same period. A board member at Peca — a seasoned and respected business veteran — grows alarmed and concludes that Peca has a quality problem. She sends memos to the executive team saying, “We have to solve our quality problem and we have to do it now!” The executive team starts chasing down the quality issues.

The Peca Products executive team is falling into the availability trap. Because someone who is known to be smart and savvy and experienced says the company has a quality problem, the executives believe that the company has a quality problem. But what if it’s a customer service problem? Or a logistics problem? Peca’s executives may well be solving exactly the wrong problem. No one stopped to ask for additional information. Rather, they relied on the available information. After all, it came from a trusted source.

So, what to do? The first thing to remember in making any significant decision is to ask questions. It’s not enough to ask questions about the information you have. You also need to seek out additional information. Questioning also allows you to challenge a superior in a politically acceptable manner. Rather than saying “you’re wrong!” (and maybe getting fired), you can ask, “Why do you think that? What leads you to believe that we have a quality problem?” Proverbs says that “a gentle answer turneth away wrath”. So does an insightful question.