Donald, Bernie, and Belittlement

Singing from the same hymnal.

What do Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump have in common?

In addition to being old, white, and angry, they both use an ancient rhetorical technique known as attributed belittlement. The technique has survived at least since the days of Aristotle. It survives because it’s simple and effective.

Attributed belittlement works because nobody likes to be humiliated. If I tell you that Joe thinks you’re a low-life, no-account, I’ll probably get a rise out of you. What I say about Joe may not be true, but that’s not the point. I want you to feel humiliated. To accomplish that, I’ve attributed to Joe belittling thoughts about you. I want to make you so angry that you don’t even think about whether I’m telling the truth. I want to manipulate you into focusing your anger on Joe. I want to short-circuit your critical thinking apparatus.

The technique works even better with groups than with individuals like Joe. You can get to know an individual. Perhaps you already know Joe and you like him. That casts doubt on my veracity. But with a group – nameless, faceless bureaucrats, for instance – it’s easy to imagine the worst. They hate us. They look down on us. They take advantage of us. Belittlement works best when we can profile an entire group of people. It’s not logical but it’s effective.

So, let’s imagine the following quote:

They look down on you. They think they’re superior to you. They think you’re here to serve them. They think they can push you around. They’ve taken your jobs and your money and now they just want to rub your nose in it.

Would this quote come from Donald or Bernie? Well, … it depends on who “they” are. If we’re talking about immigrants and religious minorities, it seems like something the Donald would say. If, on the other hand, we’re talking about billionaires and fat cats, it’s more likely something that Bernie would say.

Note the rhetorical device. While talking to you, the speaker attributes horrible thoughts to other people. These are people who are easy to caricature. They’re also easy to profile: after all, they all think alike, don’t they? They’re also not here to defend themselves. Whether you’re Donald or Bernie, it’s an easy way to score cheap points.

By the way, I’m not an innocent bystander here. I sold software for mid-sized companies and often competed against some very big fish. I told prospective customers that, “The big software companies don’t want your business. You don’t generate enough revenue. They won’t give their best service. You’re just a little fish in a big pond.” It didn’t work every time. But when it did, it worked very well.

The good thing about attributed belittlement is that it’s easy to spot. Someone is talking to you about another group or company or person who is not physically present. The speaker attributes belittling thoughts to the third party. It’s a good time to say, “Hey, wait a minute! You’re using attributed belittlement to make me angry. You must think I’m stupid.”

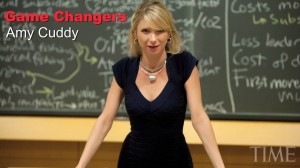

Posture, Attitude, and Amy Cuddy

Power Pose.

Suellen and I went to the Tattered Cover bookstore (a Denver icon) last night to hear Amy Cuddy speak about her new book, Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self To Your Biggest Challenges.

I’ve written about Cuddy before (here, here, and here) and use some of her work in my Critical Thinking class. We all have a general understanding of how the mind affects the body. Cuddy asks us to consider the reverse – how does the body affect the mind? Cuddy points out that the way we carry ourselves – our posture and body language – can affect our mood, thoughts, and performance. She introduces the topic quite well in her famous TED talk – the second most watched TED talk ever.

Cuddy writes that our posture affects our power over ourselves (as opposed to power over other people). When we adopt an expansive posture – making ourselves big – our power to manage ourselves and perform optimally increases. When we adopt a drawn-in posture – making ourselves small – we give away power over our own performance.

Cuddy has covered this ground before (here and here, for instance). So, what’s new? Here’s what I learned in last night’s talk:

- It’s not about outcomes; it’s about process – Cuddy gets thousands of e-mails from people who explain that they didn’t do well in a challenging process, like a job interview or an audition. But they’re not asking for advice on how to change the outcome. Instead, they’re asking how to perform the process better. This strikes me as being akin to decision theory — judging decision quality focuses on the process, not the outcome.

- It’s about your authentic self – when we are present, our body language and our spoken language reinforce each other. When we’re not present, our body language tells a different story than our spoken language.

- Two minutes is overemphasized – in her TED talk, Cuddy explains that holding an expansive posture – a power pose – for two minutes will change our hormones in positive ways. She explained last night that two minutes is not a magic number; even a few seconds is helpful.

- Animals helped us develop this idea … — Cuddy noted the influence of the naturalist Frans de Waal who explained, in his classic book, Chimpanzee Politics, how chimps adopt expansive postures to get what they want.

- … and we can, in turn, help animals – a horse trainer (@seriouspony) who was familiar with Cuddy’s work tried posture therapy on one of her Icelandic ponies who was suffering from “profound depression”. Here’s a video that shows the results.

- It has an impact on PTSD – Cuddy mentioned her friend and fellow researcher, Emma Seppälä, who has used posture therapy on combat veterans with PTSD. The results are encouraging.

- Gender – little boys and girls are equally likely to adopt expansive poses. But by the age of six (roughly) girls are starting to adopt more drawn-in poses while boys continue to be expansive. Cuddy suggests that, if we want to promote gender equality, we might start by changing this learned behavior.

- Imagination – it’s not always convenient to strike a power pose. Cuddy believes that simply imagining yourself in a power pose can be beneficial.

- Even the master needs reminders – Cuddy explained how an Internet troll had put her in a funk. Her husband reminded her to check and change her body language. She now carries a copy of her own book with a hand written note: “Remember to take your own advice”. Bottom line – we need to think about our body language; it doesn’t just change by itself.

- Where to next? – Cuddy’s many correspondents have noted that people on the autism spectrum and people with dementia both tend to adopt drawn-in postures. They make themselves small. Cuddy wonders if helping them learn to make themselves big would help.

Cuddy is a fascinating speaker – her body language definitely reinforces here spoken language. I recommend the book. Just remember that were you stand depends on how you stand.

How Many Friends Can You Have?

No point in making it bigger.

Three years ago, I wrote an article about Dunbar’s number and how it affects my business. To recap briefly, Robin Dunbar is a British anthropologist who studies primates and their social circles. He noted an interesting correlation – monkeys with small neocortexes (relative to the rest of the brain) also had small social circles. Monkeys with larger neocortexes had larger social circles. These findings became the basis of the social brain hypothesis – that our brains put an upper limit on our social relationships.

Dunbar plotted the correlation – it moved up and to the right on a two-dimensional chart – and projected it to larger primates known as humans. Dunbar’s data suggest that the “natural” upper limit for human social circles is around 150 people.

That correlates roughly with my consulting experience. Many of my clients are small software companies that call me when they reach approximately 150 employees. They’re experiencing growing pains and they need some help. I’m happy to oblige.

The data suggest that our brain capacity – and especially our ability to think abstractly – somehow limits the size of the social circles we can maintain. But what if there’s a simpler explanation? As we know, simpler explanations are usually better.

What if the cause is simply the time it takes to maintain relationships? It takes time and effort to maintain a relationship and keep it active. What if we could use advanced technologies to reduce the “time cost of servicing a relationship”? Would that allow us to expand our relationships and maintain larger social networks?

Professor Dunbar hypothesized that social media could reduce the time cost of managing and maintaining relationships. Thus, it’s possible that people who are active on social media could maintain larger networks than people who maintain only traditional, offline, face-to-face networks.

Dunbar also hypothesized that social media might influence the “distinctive series of hierarchically inclusive layers that have a natural scaling ratio of approximately 3.“ Previous research had shown that primates – both humans and monkeys – have concentric layers of relationships. For humans, the first and most intimate layer typically has five people in it. The next layer out typically has no more than 15 – or three times more than the first layer. Subsequent layers have 50 and 150 members. Each subsequent layer roughly triples the previous layer. (The innermost layer is often referred to as the support clique, the second layer as the sympathy group).

So, by reducing time costs, do social media: 1) increase the total number of relationships? and/or; 2) change the distribution or size of the relationship layers?

The short answers are: no and no. (The full research article is here.) Dunbar’s researchers took two large samples of British adults (using different sampling methods) and found that:

- The average social group size hovered around 150 – as predicted by the social brain hypothesis.

- The two innermost layers – support clique and sympathy group – hovered around five and 15 members, as found in previous studies.

- Heavy use of social network sites does not increase the total social group size. Nor does it appear to change the size of each layer.

- Women have larger social networks than men (regardless of social media use), “…with females generally having larger networks at any given layer than males.” The differences are small but consistent.

- Younger people have larger total networks than older people but the two innermost layers are approximately the same regardless of age.

What’s it all mean? We humans have “natural” limits to relationship networks that are largely consistent across gender and age groups and impervious to timesaving technical advances (at least in Britain). For me, this suggests that there’s no point in trying to grow our total network. It’s more important to invest in our innermost layers to enrich them and ensure that they don’t decay over time.

Conned By The Force

Con artist.

(Warning: spoilers ahead.)

I finally got around to seeing Star Wars: The Force Awakens the other day. It was pretty much what I expected – lots of action, lots of explosions, and a shocking shortage of suggestive double entendres. It’s a very earnest movie.

Here’s what I didn’t expect: I didn’t expect to be conned. But, boy, was I ever. And I fell for it like … well, like a death star falling into a black hole.

As always, it’s a story of good and evil, of course. The vile, evil bad guy is Kylo Ren who dresses like a fashionable Darth Vader. Though we can’t see his face, we know he’s young — the script tells us so several times. Since he’s young, we assume he’s impressionable and, perhaps, redeemable.

And redmption is exactly what we expect when an aging Han Solo confronts him, man-to-man and mano-a-mano. We’re just sure that the wise and wizened Han can save Kylo’s young soul and bring him back to the bright side. (Cue Monty Python: always look on the bright side of life).

And it works! Kylo drops his mask. His eyes fill with tears. His lips tremble. With evident emotion, he hands Han his most terrible weapon, the lightsaber. Han reaches for the weapon and we’re convinced that Kylo is about to be redeemed. Han grasps the saber and we know that angelic music will soon swell to celebrate Kylo’s conversion.

But, no. It doesn’t work out that way. I was conned. More to the point – and with much more devastating effect – Han was conned.

As I look back on the scene, I think: I should have seen that coming from a parsec away. But I didn’t. I wanted to believe. I got conned.

Why was I conned? According to Maria Konnikova, it’s because I wanted to be conned. In her new book, The Confidence Game, Konnikova writes that the con game is “…the oldest story ever told.” Simply put, we’re wired to believe. We want to believe. If we’re unsure about the future, we want someone to tell us a story to reassure us. It doesn’t have to be logical. It simply has to be believable. Since we want desperately to believe, the bar is set pretty low.

The Kylo Ren con also worked on me because I already knew the story. It’s the prodigal son. I’ve always loved the story of the prodigal son, perhaps because I was one. So I was primed. I knew how it’s supposed to end. I half-expected Han to kill a fatted calf and say, My son was lost but now he is found. That’s the way it always happens, doesn’t it? That’s what I want to believe.

Konnikova writes that we ultimately are the enablers of con artists:

“In some ways, confidence artists … have it easy. We’ve done most of the work for them; we want to believe in what they’re telling us. Their genius lies in figuring out what, precisely, it is we want and how they can present themselves as the perfect vehicle for delivering on that desire.”

So how can we protect ourselves against con artists? More on that in future articles. In the meantime, you might consider some traditional Minnesota wisdom: You’re not so special.

Questions or Answers?

Question or answer?

Which is more important: questions or answers?

Being a good systems thinker, I used to think the answer was obvious: answers are more important than questions. You’re given a problem, you pull it apart into its subsystems, you analyze them, and you develop solutions.

But what if you’re analyzing the wrong problem?

I thought about this yesterday when I read a profile of Alejandro Aravena, the Chilean architect who just won the Pritzker Prize. Aravena and his colleagues – as you might imagine – develop some very creative ideas. They do so by focusing on questions rather than answers. (Aravena’s building at the Universidad Católica de Chile is pictured).

In 2010, for instance, Aravena’s firm, Elemental, was selected to help rebuild the city of Constitución after it was hit by an earthquake and tsunami. I would have thought that they would focus on the built environment – buildings, infrastructure, and so on. They’re architects, after all. Isn’t that what architects do?

But Aravena explains it differently:

“We asked the community to identify not the answer, but what was the question,” Mr. Aravena said. This, it turned out, was how to manage rainfall, so the firm designed a forest that could help prevent flooding.

Architects, then, designed a forest instead of a building. If they were thinking about answers rather than questions, they might have missed this altogether.

On a smaller scale, I had a similar experience early in my career when I worked for Solbourne Computer. We build very fast computers – in 1988, Electronics magazine named our high-end machine the computer of the year. Naturally, we positioned our messages around speed, advanced technology, and throughput.

But our early customers were actually buying something else. When we interviewed our first dozen customers, we found that they were all men, in their early thirties, and that they had recently been promoted to replace an executive who had been in place for many years. They bought our computers to mark the changeover from the old regime to the new regime. They were meeting a sociological need as much as a technical need.

When you go to a gas station to fill your car’s tank, you may imagine that you’re buying gasoline. But, as the marketing guru Ted Levitt pointed out long ago, you’re really buying the right to continue driving your car. It’s a different question and a broader perspective and may well lead you to more creative ways to continue driving.

More recently, another marketing guru, Daniel Pink, wrote that products and services “… are far more valuable when your prospect is mistaken, confused or completely clueless about their true problem.” So often our market research focuses on simple questions about obvious problems. The classic question is, “What keeps you up at night?” We identify an obvious problem and then propose a solution. Meanwhile, our competitors are identifying the same problem and proposing their solutions. We’re locked into the same problem space.

But if we step back, look around, dig a little deeper, observe more creatively, and ask non-obvious questions, we may find that the customer actually needs something completely different. Different than what they imagined – or we imagined or our competitors imagined. They may, in fact, need a forest not a building.