How Many Friends Can You Have?

No point in making it bigger.

Three years ago, I wrote an article about Dunbar’s number and how it affects my business. To recap briefly, Robin Dunbar is a British anthropologist who studies primates and their social circles. He noted an interesting correlation – monkeys with small neocortexes (relative to the rest of the brain) also had small social circles. Monkeys with larger neocortexes had larger social circles. These findings became the basis of the social brain hypothesis – that our brains put an upper limit on our social relationships.

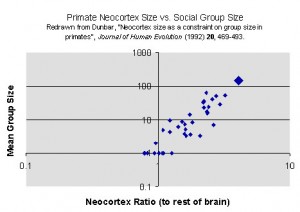

Dunbar plotted the correlation – it moved up and to the right on a two-dimensional chart – and projected it to larger primates known as humans. Dunbar’s data suggest that the “natural” upper limit for human social circles is around 150 people.

That correlates roughly with my consulting experience. Many of my clients are small software companies that call me when they reach approximately 150 employees. They’re experiencing growing pains and they need some help. I’m happy to oblige.

The data suggest that our brain capacity – and especially our ability to think abstractly – somehow limits the size of the social circles we can maintain. But what if there’s a simpler explanation? As we know, simpler explanations are usually better.

What if the cause is simply the time it takes to maintain relationships? It takes time and effort to maintain a relationship and keep it active. What if we could use advanced technologies to reduce the “time cost of servicing a relationship”? Would that allow us to expand our relationships and maintain larger social networks?

Professor Dunbar hypothesized that social media could reduce the time cost of managing and maintaining relationships. Thus, it’s possible that people who are active on social media could maintain larger networks than people who maintain only traditional, offline, face-to-face networks.

Dunbar also hypothesized that social media might influence the “distinctive series of hierarchically inclusive layers that have a natural scaling ratio of approximately 3.“ Previous research had shown that primates – both humans and monkeys – have concentric layers of relationships. For humans, the first and most intimate layer typically has five people in it. The next layer out typically has no more than 15 – or three times more than the first layer. Subsequent layers have 50 and 150 members. Each subsequent layer roughly triples the previous layer. (The innermost layer is often referred to as the support clique, the second layer as the sympathy group).

So, by reducing time costs, do social media: 1) increase the total number of relationships? and/or; 2) change the distribution or size of the relationship layers?

The short answers are: no and no. (The full research article is here.) Dunbar’s researchers took two large samples of British adults (using different sampling methods) and found that:

- The average social group size hovered around 150 – as predicted by the social brain hypothesis.

- The two innermost layers – support clique and sympathy group – hovered around five and 15 members, as found in previous studies.

- Heavy use of social network sites does not increase the total social group size. Nor does it appear to change the size of each layer.

- Women have larger social networks than men (regardless of social media use), “…with females generally having larger networks at any given layer than males.” The differences are small but consistent.

- Younger people have larger total networks than older people but the two innermost layers are approximately the same regardless of age.

What’s it all mean? We humans have “natural” limits to relationship networks that are largely consistent across gender and age groups and impervious to timesaving technical advances (at least in Britain). For me, this suggests that there’s no point in trying to grow our total network. It’s more important to invest in our innermost layers to enrich them and ensure that they don’t decay over time.

Dunbar’s Number: Why My Clients Hire Me?

I’ve noticed a pattern among my clients. Many of them are small software companies with good ideas that are growing rapidly. When they first call me, they have approximately 150 employees. I’ve often wondered, what is it that triggers a problem — and a call to an outsider — at 150 employees?

Then I discovered Dunbar’s number and the pattern started to make sense. Robin Dunbar, a British anthropologist, is an expert on the social lives of monkeys. (Wouldn’t you love to have a job like that?) Dunbar made an interesting observation: Monkeys with small brains have small social circles. Monkeys with larger brains have larger social circles. Actually, it’s not total brain size — it’s the size of the neocortex, the area of the brain where we do our abstract reasoning. In Dunbar’s charts, you’ll find a distinct up-and-to-the-right relationship between the size of the neocortex (relative to the rest of the brain) and the size of the social group.

So, you might wonder, how does this affect the lives of large-brained primates known as humans? How big is our “natural” social group? Funny you should ask. Dunbar frames the question this way: what’s the largest number of people in which it’s possible for everyone to know each other and also to know how everyone relates to everyone else? The answer is slippery but it seems to be around 150 people (plus or minus, oh, say 30).

How many for humans?

If you search the topic on the web, you’ll find a number of observers arguing for a higher number. (I didn’t find any arguing for a lower number). On the other hand, you’ll also find observers who claim that 150 occurs frequently and “naturally” in traditional societies. Apparently, the Roman Legions were divided into companies of 150 men. Church parishes in 18th century England contained 150 people. If your parish grew bigger, the bishop would campaign for an additional church.

How does Dunbar’s number affect organizations? Generally speaking, a smaller organization can be fairly loosey-goosey. We all know each other and we all know how we relate to each other. We don’t need a lot of structure. Above 150, however, organizations start to get more bureaucratic. According to Wikipedia, “…analysts assert that organizations with populations of people larger than Dunbar’s number … generally require more restrictive rules, laws, and enforced norms, to maintain a stable, cohesive group.”

Maybe this is why companies call me when they reach about 150 employees. They’re growing up and they’re feeling the growing pains. It’s not as simple as it used to be. In fact, it’s getting rather complicated. I hope they keep calling me. I’m becoming a bit of a specialist.

You can find Dunbar’s original article here.