Intuition — Wicked and Kind

My intuition is good here.

When I was climbing mountains regularly, I thought I had pretty good intuition. Even if I didn’t know quite why I was making a decision, I generally made pretty good decisions. I usually made conservative as opposed to risky decisions. Intuitively, I could reasonably judge whether a decision was too conservative, too risky, or just right.

When I was an executive, on the other hand, my intuition for business decisions was not especially good. I didn’t have a “feel” for the situation. In the mountains, I could “fly by the seat of my pants.” In the executive suite I needed reams and reams of analysis. I couldn’t even tell whether a decision was conservative or risky – it depended on how you defined the terms. As a businessman, I often longed for the certainty and confidence I felt in the mountains.

What’s the difference between the two environments? The mountains were kind; the executive suite was wicked.

The concepts of “kind” and “wicked” come from Robin Hogarth’s book, Educating Intuition. Hogarth’s central idea is that we can teach ourselves to become more intuitive and more insightful. We have some control over the process, but the environment – whether kind or wicked — also plays a critical role.

Where does intuition come from? I wasn’t born with the ability to make good decisions in the mountains. I must have learned it from my experiences and from my teachers. I never set a goal to become more intuitive. My goal was simply to enjoy myself safely in wilderness environments. Creating an intuitive sense of the wilderness was merely a byproduct.

But why would I be better at wilderness intuition than at business intuition? According to Hogarth, it has to do with the nature, quality, and speed of the feedback.

In the mountains, I often got immediate feedback on my decisions. I could tell within a few minutes whether I had made a good decision or not. At most, I had to wait for a day or two. The feedback was also unambiguous. I knew whether I had gotten it right or not.

In a certain way, however, mountain decisions were difficult to evaluate. The act of making a decision meant that I couldn’t make comparisons. Let’s say I chose Trail A as opposed to Trail B. Let’s also assume that Trail A led directly to the summit with minimal obstacles. I might conclude that I had made a good decision. But did I? Trail B might have been even better.

So, in Hogarth’s terminology, mountain decision-making was kind in that it was clear, quick, and unambiguous. It was less kind in that making one decision eliminated the possibility of making useful comparisons. Compare this, for instance, to predicting that it will rain tomorrow. Making the prediction doesn’t, in any way, reduce the quality of the feedback.

Now compare the mountain environment to the business environment. The business world is truly wicked. I might not get feedback for months or years. In the meantime, I may have made many other decisions that might influence the outcome.

The feedback is ambiguous as well. Let’s say that we achieve good results. Was that because of the decision I made or because of some extraneous, or even random factors? And, like Trail A versus Trail B, choosing one course of action eliminates the possibility of making meaningful comparison.

It’s no wonder that I had better intuition in the mountains than in the executive suite. With the exception of the Trail A/Trail B issue, the mountains are a kind environment. The business world, on the other hand, offers thoroughly wicked feedback.

Could I ever develop solid intuition in the wicked world of business? Maybe. I’ll write more on how to train your intuition in the near future.

How Long Does It Take (To Have A Good Idea)?

Developing a slow hunch.

Friends often ask me how long it takes to write one of my web articles. I can frame the question narrowly or broadly. In the narrow frame, the answer might be 90 minutes or so. In the broad frame, it might be 30 years or so. Talk about a slow hunch.

I’ll illustrate with my most recent article: Hate, Happiness, Imagination. As with many things – especially innovations – the article is a mashup of several different sources and concepts. Let’s track them in chronological order.

The first idea came to me through Graham Greene’s brilliant novel, The Power and the Glory. The novel includes a lovely quote: “Hate is the failure of imagination”. Greene wrote the novel in 1940, so the idea is now at least 75 years old (or perhaps older since Greene seems to echo previous authors).

I read the novel when Suellen and I lived in Guanajuato, Mexico in 1980. The quote about hate and imagination struck me and has stuck with me ever since. So, I’ve been gestating the idea for 35 years. I would occasionally mention it to friends but, otherwise, I didn’t do much with it.

In 2005, David Foster Wallace gave his famous commencement speech at Kenyon College. He stressed that, all too often, we fail to imagine what life is like for other people. If we did use our imagination more fully, we would empathize more, and our lives would be richer and fuller. First, we have to recognize that we can make a choice — that we don’t have to operate on our egocentric default setting. Second, we actually have to make the choice.

I didn’t know about Wallace’s speech until I started teaching critical thinking. As I looked for sources, I came across a video of the (abridged) speech and used it several times in my class. I first stumbled across it in 2012.

I didn’t do much with the Kenyon College speech until a few weeks ago. Frankly, I had forgotten about it. Then one of my students discovered it and asked me to show it to the class. That led to a very healthy discussion during which I connected what Wallace said to what Greene wrote.

Bingo! I made the connection between the two ideas. Why did it take me so long? Probably because I was just thinking about it. Thinking is fine but I don’t think that merely thinking creates many new ideas. The give-and-take of the class discussion stimulated me to make new connections. The diversity of opinions helped me open up new connections rather than merely deepening old connections.

Still, I didn’t have a complete thought. Then Suellen read me a paragraph from a review of the new biography of Saul Bellow. The review mentioned Bellow’s belief that imagination is “eternal naïveté”. When I realized what he meant by that, it dawned on me that it completed the thought. Greene connected to Wallace connected to Bellow.

What can we learn from this? First, this little story illustrates Steven Johnson’s idea of the “slow hunch”. Many good ideas – and most innovations – result from mashing up existing ideas. Unfortunately, we don’t get those ideas simultaneously. We may get one in 1980, another in 2012, and another last month. The trick is to remember the first one long enough to couple it with the second one. (Writing a blog helps).

The other point is that the pure act of thinking is (often) not enough. We need to kick ideas around with other people. Diversity counts. I’m lucky that I can kick ideas around with my students. And with Suellen. If not for them, I wouldn’t be nearly as interesting as I am.

So, how long does it take me to have a good idea? About 35 years.

Somatopsychic Chewing Gum

No flu here!

Psychosomatic illness is one that is “caused or aggravated by a mental factor such as internal conflict or stress”. We know that the brain can create disturbances in the body. But what about the other way round? Can we have somatopsychic illnesses? Or could the body produce somatopsychic wellness – not a disease but the opposite of it?

I’ve written about embodied cognition in the past (here, here, and here). Our body clearly influences the way we think. But could our body influence the way we think and our thinking, in turn, influence our body? Here are some interesting phenomena I’ve discovered recently in the literature.

Exercise and mental health – I’ve seen a spate of articles on the positive effects of physical exercise on mental health. This truly is a somatopsychic effect. Among other things, raising your heartbeat increases blood flow to your brain and that’s a very good thing. Exercise also reduces stress, elevates your mood, improves your sleep, and – maybe, just maybe – improves your sex life.

Chewing gum and annoying songs – ever get an annoying song in your head that just won’t go away? For me, it’s the theme from Gilligan’s Island. New research suggests that chewing gum could alleviate – though not completely eliminate – the song. One researcher noted that, “producing movements of the mouth and jaw [can] affect memory and the ability to imagine music.” Why jaw movements would affect memory is anyone’s guess.

Hugs and colds – could hugging other people help you reduce your chances of catching a cold? You might think that hugging other people – especially random strangers – would increase your exposure to cold germs and, therefore, to colds. But it seems that the opposite is, in fact, the case. The more you hug, the less likely you are to get a cold. Hugging is a good proxy for your social support network. People with strong social support are less likely to get sick (or to die, for that matter). Even if you don’t have strong social support, however, increasing your daily quota of hugs seems to have a similar effect.

Sitting or standing? – do you think better when you’re sitting down or standing up? At least for young children – ages seven to 10 – standing up seems to produce much better results. Side benefit: standing at a desk can burn 15% to 25% more calories than sitting. Maybe this is why it’s a good thing to be called a stand-up guy.

Clean desk or messy desk (and here) – it depends on what behavior you’re looking for. People with clean desks are more likely “to do what’s expected of them.” They tend to conform to rules more closely and behave in more altruistic ways. People at messy desks, on the other hand, were more creative. The researchers conclude: “Orderly environments promote convention and healthy choices, which could improve life by helping people follow social norms and boosting well-being. Disorderly environments stimulated creativity, which has widespread importance for culture, business, and the arts.”

So, what does it all mean? As we’ve learned before, the body and the brain are one system. What one does affects the other. Behavior and thinking are inextricably intertwined. When your brain wanders, don’t let your feet loaf.

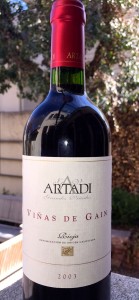

My Brain Is Ripening

My brain is aging like a fine wine.

What cognitive advantages do young people have over me? Not as many as we once thought.

We once assumed that our brains grew until, oh say, our mid-twenties and then gradually declined until death. We had what we had and would never get any more. As cells died, they weren’t replaced. After reaching its peak, the brain was essentially static – it couldn’t grow or enrich itself. It could only decay.

A new paradigm holds that the brain is plastic – it can grow and change and build new connections well into our mature years. It may even be possible to do brain exercises to improve our mental performance.

This model generally divides intelligence into two types: fluid and crystallized. Fluid intelligence is the ability to think critically and manage effectively in novel situations. People with fluid intelligence can reason their way through unfamiliar territory by recognizing patterns and relationships. They figure out stuff on the fly.

People with crystallized intelligence have valuable facts and data stored in their brains and know what to do with it. (I have some data and I know how to use it!) It’s all about what we’ve experienced, learned, and remembered over a lifetime.

Young people tend to excel at fluid intelligence. Why? They get more practice. Since they don’t have many experiences, a greater proportion of their experiences will be novel. When our 14-year-old niece spent a summer with us in Stockholm, everything was new to her. She experienced her first taxicab, her first subway, and her first molten chocolate cake. She had plenty of chances to hone her fluid intelligence.

Older people, on the other hand, tend to have more crystallized intelligence. I experienced my first subway long ago. I learned from the experience and stored what I learned somewhere in memory (where it crystallized). I can deal with subways because I know about them. I don’t need to spot new patterns; I already recognize them. As I deal with fewer novel situations, my fluid intelligence gets rusty.

Now, there’s a new, new paradigm of brain function. It’s not just fluid versus crystallized. Rather, there are multiple cognitive skills and they peak at different times in our lives.

The new view is exemplified in the work of Laura Germine and Joshua Hartshorne. Germine and Hartshorne have recruited thousands of people of all ages to play mental games at testmybrain.org and gameswithwords.org. The resulting data allow the researchers to identify different cognitive skills and relate them to different age ranges. (The original paper is here. A less technical overview is here).

Here’s a summary of what they found:

Peak mental processing speed occurs, as expected, in late teens and early 20s and declines relatively rapidly afterward. But other skills peak at different times. Working memory climbs in the late 20s to early 30s, and then declines only slowly over time. Social cognition, the ability to detect others’ emotions, peaks even later — in the 40s to age 50 — and doesn’t start to significantly decline until after 60. …. Crystalized intelligence, measured as vocabulary skills, didn’t have a peak. Instead, it continued to improve as respondents aged, until 65 to 70.

The finding that crystallized intelligence doesn’t peak until 65 to 70 seemed to contradict earlier studies. When Germine and Hartshorne analyzed earlier studies however, they found that the peak itself rose over time. Studies conducted in the seventies, for instance, suggested that crystallized intelligence peaked in the early 40s. Studies conducted in the eighties and nineties found a later peak: around 50. Studies conducted since 1998 showed an even later peak: around 65. So, perhaps, our entire society is getting smarter.

So don’t assume that my brain is declining as I age. Rather, in Germine’s phase, it’s ripening. Maybe yours is, too.

Do Smartphones Make Us Smarter, Dumber, Or Happier?

So which is it?

Smartphones:

- Make you lazy and dumb.

- Make the world more intelligent by adding massive amounts of new processing power.

- Both of the above.

- None of the above.

Smartphones have an incredible impact on how we live and communicate. They also illustrate a popular technology maxim: If it can be done, it will be done. In other words, they’re not going away. They’ll grow smaller and stronger and will burrow into our lives in surprising ways. The basic question: are they making humans better or worse?

Smarter or dumber?

Researchers at the University of Waterloo in Canada recently published a paper suggesting that smartphones “supplant thinking”. The researchers suggest that humans are cognitive misers — we conserve our cognitive resources whenever possible. We let other people – or devices – do our thinking for us. We make maximum use of our extended mind. Why use up your brainpower when your extended mind – beyond your brain – can do it for you? (The original Waterloo paper is here. Less technical summaries are here and here).

Though the researchers don’t use Daniel Kahneman’s terminology, there is an interesting correlation to System 1 and System 2. They write that, “…those who think more intuitively and less analytically [i.e. System 1] when given reasoning problems were more likely to rely on their Smartphones (i.e., extended mind) ….” In other words, System 1 thinkers are more likely to offload.

So, we use our phones to offload some of our processing. Is that so bad? We’ve always offloaded work to machines. Thinking is a form of work. Why not offload it and (potentially) reduce our cognitive load and increase our cognitive reserve? We could produce more interesting thoughts if we weren’t tied down with the scut work, couldn’t we?

Clay Shirky was writing in a different context but that’s the essence of his concept of cognitive surplus. Shirky argues that people are increasingly using their free time to produce ideas rather than simply to consume ideas. We’re watching TV less and simultaneously producing more content on the web. Indeed, this website is an example of Shirky’s concept. I produce the website in my spare time. I have more spare time because I’ve offloaded some of my thinking to my extended mind. (Shirky’s book is here).

Shirky assumes that creating is better than consuming. That’s certainly a culturally nuanced assumption, but it’s one that I happen to agree with. If it’s true, we should work to increase the intelligence of the devices that surround us. We can offload more menial tasks and think more creatively and collaboratively. That will help us invent more intelligent devices and expand our extended mind. It’s a virtuous circle.

But will we really think more effectively by offloading work to our extended mind? Or, will we forevermore watch reruns of The Simpsons?

I’m not sure which way we’ll go, but here’s how I’m using my smartphone to improve my life. Like many people, I consult my phone almost compulsively. I’ve taught myself to smile for at least ten seconds each time I do. My phone reminds me to smile. I’m not sure if that’s leading me to higher thinking or not. But it certainly brightens my mood.