Surviving The Survivorship Bias

You too can be popular.

Here are three articles from respected sources that describe the common traits of innovative companies:

The 10 Things Innovative Companies Do To Stay On Top (Business Insider)

The World’s 10 Most Innovative Companies And How They Do It (Forbes)

Five Ways To Make Your Company More Innovative (Harvard Business School)

The purpose of these articles – as Forbes puts it – is to answer a simple question: “…what makes the difference for successful innovators?” It’s an interesting question and one that I would dearly love to answer clearly.

The implication is that, if your company studies these innovative companies and implements similar practices, well, then … your company will be innovative, too. It’s a nice idea. It’s also completely erroneous.

How do we know the reasoning is erroneous? Because it suffers from the survivorship fallacy. (For a primer on survivorship, click here and here). The companies in these articles are picked because they are viewed as the most innovative or most successful or most progressive or most something. They “survive” the selection process. We study them and abstract out their common practices. We assume that these common practices cause them to be more innovative or successful or whatever.

The fallacy comes from an unbalanced sample. We only study the companies that survive the selection process. There may well be dozens of other companies that use similar practices but don’t get similar results. They do the same things as the innovative companies but they don’t become innovators. Since we only study survivors, we have no basis for comparison. We can’t demonstrate cause and effect. We can’t say how much the common practices actually contribute to innovation. It may be nothing. We just don’t know.

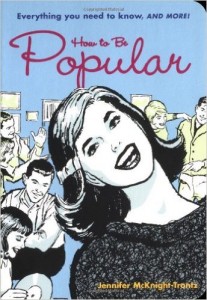

Some years ago, I found a book called How To Be Popular at a used-book store. Written for teenagers, it tells you what the popular kids do. If you do the same things, you too can be popular. It’s cute and fluffy and meaningless. In fact, to someone beyond adolescence, it’s obvious that it’s meaningless. Doing what the popular kids do doesn’t necessarily make your popular. We all know that.

I bought the book as a keepsake and a reminder that the survivorship fallacy can pop up at any moment. It’s obvious when it appears in a fluffy book written for teens. It’s less obvious when it appears in a prestigious business journal. But it’s still a fallacy.

Ethics And The Self-Driving Car

Why does it have to look like a car?

In last night’s critical thinking class, we discussed and debated how to instill ethics into self-driving cars. To kick off the debate, I adapted a question from an article by Will Knight in a recent issue of Technology Review.

If a child runs in front of a self-driving car, is it ethical for the car to injure or kill its own passengers in order to avoid the child?

The question split the class roughly in two. Some students argued that the car should avoid the child at all costs – even at the risk of serious injury or death to the car’s passengers. Others argued that the life of the person in the car was at least equal to that of the child. And if the car contains more than one passenger, wouldn’t multiple lives outweigh the value of one child’s life? Why should the child alone be protected?

The students also weighed the value of different lives. I asked them to assume that I was in the car. So the question became: Which is more valuable, the life of a child or the life of a mature adult? Some argued that the child was more valuable because she has many years of life yet to live. By comparison, I have lived many years and “used up” some of my value.

Others argued exactly the opposite. A mature adult is a storehouse of knowledge and wisdom. To lose that would be a blow not only to the individual but also to the community. The death of a child, though tragic, would eliminate only a small quantity of wisdom.

The question then evolves to: Could we have different ethical systems in cars that are used in different cultures? For instance, could cars that are used in cultures that value older people as fonts of wisdom, use an ethical system that protects adults over children? At the same time, could cars used in youth-oriented cultures, opt to protect children ahead of adults? What are the ethics here?

As you may have noticed, we were all making one key assumption: that self-driving cars will be delivered with an ethical system already installed. Let’s change that assumption. Let’s say the car arrives in your driveway (it delivers itself presumably) with no ethical rules programmed into it. The first thing we do is to program in the rules that we believe are the most ethical. The rules I program into my car may be different than the rules you put in your car.

This is, of course, exactly what we do today. When I drive my car, it’s controlled by my ethical system. Your ethical system controls your car. Our ethics may be different, so our cars “behave” differently. We’re quite used to that in everyday life, partially because the rules are not explicit. But as we explicitly program ethics into cars, is that really the way we want to do it?

Pushing on, we also addressed questions of self-driving cars with no passengers. We generally assume that self-driving cars will have passengers and at least one of those will be a responsible adult. But do they have to? Here are two variants:

- I want a pizza. Is it ethical for me to send my self-driving car to the local pizza place to pick it up for me? Conversely, could the pizza place simply deliver it to me in a self-driving car with no human in it?

- Is it ethical for a Dad to place his two kids in a self-driving car and instruct the car to deliver them to their primary school … without Dad going along? Could self-driving cars become child delivery systems?

I think we can find many more questions here. To wit: Can you own a self-driving car or is it a community resource to be shared? Does a self-driving car have to look like a regular old car? Why? (Here’s an example of one that doesn’t).

There’s a lot to think about here. Indeed, we may find that it will be more difficult to solve the ethical problems than technical problems. I’ll write more about these issues in the future. In the meantime: Safe driving!

Business School And The Swimmer’s Body Fallacy

He’s tall because he plays basketball.

Michael Phelps is a swimmer. He has a great body. Ian Thorpe is a swimmer. He has a great body. Missy Franklin is a swimmer. She has a great body.

If you look at enough swimmers, you might conclude that swimming produces great bodies. If you want to develop a great body, you might decide to take up swimming. After all, great swimmers develop great bodies.

Swimming might help you tone up and trim down. But you would also be committing a logical fallacy. Known as the swimmer’s body fallacy, it confuses selection criteria with results.

We may think that swimming produces great bodies. But, in fact, it’s more likely that great bodies produce top swimmers. People with great bodies for swimming – like Ian Thorpe’s size 17 feet – are selected for competitive swimming programs. Once again, we’re confusing cause and effect. (Click here for a good background article on swimmer’s body fallacy).

Here’s another way to look at it. We all know that basketball players are tall. But would you accept the proposition that playing basketball makes you tall? Probably not. Height is not malleable. People grow to a given height because of genetics and diet, not because of the sports they play.

When we discuss height and basketball, the relationship is obvious. Tallness is a selection criterion for entering basketball. It’s not the result of playing basketball. But in other areas, it’s more difficult to disentangle selection factors from results. Take business school, for instance.

In fact, let’s take Harvard Business School or HBS. We know that graduates of HBS are often highly successful in the worlds of business, commerce, and politics. Is that success due to selection criteria or to the added value of HBS’s educational program?

HBS is well known for pioneering the case study method of business education. Students look at successful (and unsuccessful) businesses and try to ferret out the causes. Yet we know that, in evidence-based medicine, case studies are considered to be very weak evidence.

According to medical researchers, a case study is Level 3 evidence on a scale of 1 to 4, where 4 is the weakest. Why is it so weak? Partially because it’s a sample of one.

It’s also because of the survivorship bias. Let’s say that Company A has implemented processes X, Y, and Z and been wildly successful. We might infer that practices X, Y, and Z caused the success. Yet there are probably dozens of other companies that also implemented processes X, Y, and Z and weren’t so successful. Those companies, however, didn’t “survive” the process of being selected for a B-school case study. We don’t account for them in our reasoning.

(The survivorship bias is sometimes known as the LeBron James fallacy. Just because you train like LeBron James doesn’t mean that you’ll play like him).

So we have some reasons to suspect the logical underpinnings of a case-base education method. So, let’s revisit the question: Is the success of HBS graduates due to selection criteria or to the results of the HBS educational program? HBS is filled with brilliant professors who conduct great research and write insightful papers and books. They should have some impact on students, even if they use weak evidence in their curriculum. Shouldn’t they? Being a teacher, I certainly hope so. If so, then the success of HBS graduates is at least partially a result of the educational program, not just the selection criteria.

But I wonder …

Seeing With Your Eyes

I’d be happy to check you in.

Some years ago, on a business trip, I checked into a hotel that had just implemented a new computer system. I asked the desk clerk how he liked it. He responded very positively: “It’s great. It’s so much better than the previous system.” He smiled broadly and spoke enthusiastically. I assumed that he was telling the truth.

I also noticed some telling details. He had to bend far forward to reach the keyboard. Then he had to tilt his head back to see the screen. It looked awkward to say the least. He couldn’t make eye contact with me and use the system at the same time.

More problematically, the system was rigid and field-oriented. The screen contained many fields, not all of which were necessary for each client. But you couldn’t skip a field. To get from Field A to Field Z, you had to navigate sequentially through Field B, then Field C, and so on. The poor guy must have hit the Return key a dozen times while checking me in. He couldn’t check me in and have a friendly conversation at the same time.

I noted two things about the situation. First, the man seemed genuinely pleased with the new system. He recommended it without reservation. (No pun intended). Second, the system really wasn’t very good. The man didn’t realize what he might have had.

I also thought about how I might act if I were an executive at the hotel company. If I listened to what the desk clerk said, I would congratulate the IT department, maybe give out a bonus or two, and move on to the next problem.

But if I looked instead of listening, I might have had a very different reaction. The system was awkward, physically uncomfortable, and not conducive to good customer communication. I might not have torn the system out, but I certainly would have requested an upgrade.

This is a pretty good illustration of the difference between seeing with your mind and seeing with your eyes. The desk clerk was seeing with his mind. He had a mental image of the old system (“clunky, user hostile”) and of the new system (“much improved”). He didn’t see what he was actually doing. He didn’t perceive any shortcomings because he was comparing it, not to an ideal system, but to an old system.

A good observer, on the other hand, would not compare the system to preconceived notions. A good observer would have no preconceived notions. She would merely observe and identify problems and opportunities.

My experience reminds me of the women who designed the Volvo concept car some years ago. If I were designing a car, I would assume that it “should” have a hood (bonnet) that opens. After all, all cars have hoods that open. There must be a reason. That’s a notion that I see in my mind’s eye, not in my physical eye.

The Volvo designers, on the other hand, simply observed how people used their cars. They noted that drivers rarely open the hoods. Indeed, they do so only to add windshield washer fluid. The designers asked a simple question: Why bother? They put a fluid filler opening on the outside of the car and simplified the entire front end of the car by eliminating the openable hood.

The designers created a car that is simpler, cleaner, lighter, and stronger. That’s good design. It comes from seeing the world as it is, not as it’s assumed to be.

Designing Minds

Designers.

I learned systems analysis in graduate school. I know how to use analytic tools to break a problem apart and fix the component parts. That is, I know how to use the tools if and only if I know that a problem exists. In most cases, somebody has to describe the problem to me.

Julia and Elliot, our son and daughter-in-law, learned design thinking in graduate school. They know how to observe closely and intuit what users need. They empathize and can see the world from the user’s perspective. They know how to suspend their assumptions and see the world as it is, not as it’s assumed to be. Paraphrasing Picasso, they see with their eyes, not their minds.

They also have the skills, of course, to design solutions to meet the user’s needs. They can even design solutions for problems that weren’t apparent to the user. Because of the way they observe the world, Julia and Elliot can identify problems and needs that I can’t.

Businesses are starting to realize that design thinking holds significant advantages over traditional methods of systems analysis. Design thinking is an observational skill as much as an analytical skill. It uses empathy and imagination to understand the world at a deeper level and design unexpected solutions.

What does it mean to be design-driven? McKinsey gives a simple definition: “…it’s a way of thinking: a creative process that spans entire organizations, driven by the desire to better understand and meet consumer needs.” For me, it’s not only a way of thinking but also a way of seeing. Designers see what the customer really needs, even if the customer doesn’t.

In this regard, design thinking seems similar to the art of negotiation. A successful negotiator sees what the other side needs — even when the other side doesn’t. The negotiator negotiates to that need. The designer designs to it.

In another article, McKinsey expands the definition and states a key benefit: “A design-driven organization is always thinking about its customers, empathizing with end users, and trying to solve problems while keeping its customers in mind. … Companies that have placed design at the center of the organization perform better.” (Italics added).

Design, in other words, provides a competitive edge. When I was fresh out of school, systems thinking was a competitive weapon. Today, it’s design thinking. Design used to be about things, objects, and spaces. Today, it can equally be used to create business processes and services.

The business world seems to be making a fundamental transition from analysis to design. Instead of decomposing a problem, innovative businesses are using imagination and empathy to create solutions. Julia and Elliot, in other words, have positioned themselves at the leading edge of a transformational new wave. What a great time to be young.