You Too Can Be A Revered Leader!

I just spotted this article on Inc. magazine’s website:

Want to Be A Revered Leader? Here’s How The 25 Most Admired CEOs Win The Hearts of Their Employees.

The article’s subhead is: “America’s 25 most admired CEOs have earned the respect of their people. Here’s how you can too.”

Does this sound familiar? It’s a good example of the survivorship fallacy. (See also here and here). The 25 CEOs selected for the article “survived” a selection process. The author then highlights the common behaviors among the 25 leaders. The implication is that — if you behave the same way — you too will become a revered leader.

Is it true? Well, think about the hundreds of CEOs who didn’t survive the selection process. I suspect that many of the unselected CEOs behave in ways that are similar to the 25 selectees. But the unselected CEOs didn’t become revered leaders. Why not? Hard to say …precisely because we’re not studying them. It’s not at all clear to me that I will become a revered leader if I behave like the 25 selectees. In fact, the reverse my be true — people may think that I’m being inauthentic and lose respect for me.

A better research method would be to select 25 leaders who are “revered” and compare them to 25 leaders who are not “revered”. (Defining what “revered” means will be slippery). By selecting two groups, we have some basis for comparison and contrast. This can often lead to deeper insights.

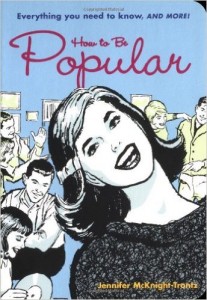

As it stands, the Inc. article reminds me of the book for teenagers called How To Be Popular. It’s cute but not very meaningful.

Surviving The Survivorship Bias

You too can be popular.

Here are three articles from respected sources that describe the common traits of innovative companies:

The 10 Things Innovative Companies Do To Stay On Top (Business Insider)

The World’s 10 Most Innovative Companies And How They Do It (Forbes)

Five Ways To Make Your Company More Innovative (Harvard Business School)

The purpose of these articles – as Forbes puts it – is to answer a simple question: “…what makes the difference for successful innovators?” It’s an interesting question and one that I would dearly love to answer clearly.

The implication is that, if your company studies these innovative companies and implements similar practices, well, then … your company will be innovative, too. It’s a nice idea. It’s also completely erroneous.

How do we know the reasoning is erroneous? Because it suffers from the survivorship fallacy. (For a primer on survivorship, click here and here). The companies in these articles are picked because they are viewed as the most innovative or most successful or most progressive or most something. They “survive” the selection process. We study them and abstract out their common practices. We assume that these common practices cause them to be more innovative or successful or whatever.

The fallacy comes from an unbalanced sample. We only study the companies that survive the selection process. There may well be dozens of other companies that use similar practices but don’t get similar results. They do the same things as the innovative companies but they don’t become innovators. Since we only study survivors, we have no basis for comparison. We can’t demonstrate cause and effect. We can’t say how much the common practices actually contribute to innovation. It may be nothing. We just don’t know.

Some years ago, I found a book called How To Be Popular at a used-book store. Written for teenagers, it tells you what the popular kids do. If you do the same things, you too can be popular. It’s cute and fluffy and meaningless. In fact, to someone beyond adolescence, it’s obvious that it’s meaningless. Doing what the popular kids do doesn’t necessarily make your popular. We all know that.

I bought the book as a keepsake and a reminder that the survivorship fallacy can pop up at any moment. It’s obvious when it appears in a fluffy book written for teens. It’s less obvious when it appears in a prestigious business journal. But it’s still a fallacy.

Business School And The Swimmer’s Body Fallacy

He’s tall because he plays basketball.

Michael Phelps is a swimmer. He has a great body. Ian Thorpe is a swimmer. He has a great body. Missy Franklin is a swimmer. She has a great body.

If you look at enough swimmers, you might conclude that swimming produces great bodies. If you want to develop a great body, you might decide to take up swimming. After all, great swimmers develop great bodies.

Swimming might help you tone up and trim down. But you would also be committing a logical fallacy. Known as the swimmer’s body fallacy, it confuses selection criteria with results.

We may think that swimming produces great bodies. But, in fact, it’s more likely that great bodies produce top swimmers. People with great bodies for swimming – like Ian Thorpe’s size 17 feet – are selected for competitive swimming programs. Once again, we’re confusing cause and effect. (Click here for a good background article on swimmer’s body fallacy).

Here’s another way to look at it. We all know that basketball players are tall. But would you accept the proposition that playing basketball makes you tall? Probably not. Height is not malleable. People grow to a given height because of genetics and diet, not because of the sports they play.

When we discuss height and basketball, the relationship is obvious. Tallness is a selection criterion for entering basketball. It’s not the result of playing basketball. But in other areas, it’s more difficult to disentangle selection factors from results. Take business school, for instance.

In fact, let’s take Harvard Business School or HBS. We know that graduates of HBS are often highly successful in the worlds of business, commerce, and politics. Is that success due to selection criteria or to the added value of HBS’s educational program?

HBS is well known for pioneering the case study method of business education. Students look at successful (and unsuccessful) businesses and try to ferret out the causes. Yet we know that, in evidence-based medicine, case studies are considered to be very weak evidence.

According to medical researchers, a case study is Level 3 evidence on a scale of 1 to 4, where 4 is the weakest. Why is it so weak? Partially because it’s a sample of one.

It’s also because of the survivorship bias. Let’s say that Company A has implemented processes X, Y, and Z and been wildly successful. We might infer that practices X, Y, and Z caused the success. Yet there are probably dozens of other companies that also implemented processes X, Y, and Z and weren’t so successful. Those companies, however, didn’t “survive” the process of being selected for a B-school case study. We don’t account for them in our reasoning.

(The survivorship bias is sometimes known as the LeBron James fallacy. Just because you train like LeBron James doesn’t mean that you’ll play like him).

So we have some reasons to suspect the logical underpinnings of a case-base education method. So, let’s revisit the question: Is the success of HBS graduates due to selection criteria or to the results of the HBS educational program? HBS is filled with brilliant professors who conduct great research and write insightful papers and books. They should have some impact on students, even if they use weak evidence in their curriculum. Shouldn’t they? Being a teacher, I certainly hope so. If so, then the success of HBS graduates is at least partially a result of the educational program, not just the selection criteria.

But I wonder …