FOMO/JOMO. Be Here Now.

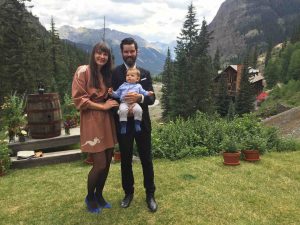

Julia and Elliot recently went to a wedding in Eureka, Colorado, a ghost town situated high in the San Juan Mountains. To say that Eureka is isolated is a vast understatement. Here are some things that the town doesn’t have: landlines, television, internet, wi-fi, mobile phone access, cable, newspapers, radio, and paved roads. When you’re there, you’re there.

Just before the wedding ceremony, ushers collected everyone’s cameras and mobile phones. The couple seemed to be saying to their guests: “We’re glad you’re here. We hope you’re with us fully and completely. Don’t fuss with your cameras and phones. Engage with us in a profound experience. Be here now.”

The place and the process reminded me of Daniel Kahneman’s definitions of the experiencing self and the remembering self. We can focus, engage our senses, and fully experience an activity. What we remember, however, is far different from what we experience. We typically remember two things: 1) the peak experience – the high point of the activity; 2) the end state – how things ended up. (For more on memory traps, click here).

The difference between the two selves has many implications. We remember things differently than they actually happened. This calls into question such things as eyewitness testimony and historical accounts. It may also be why we argue with our spouses – we simply remember things differently. It’s another good reason not to argue in the past tense. (For other reasons, click here).

The difference also affects how we plan our activities. We can plan to: 1) enhance the experience; or 2) enhance our memory of the experience. Let’s say you go to your favorite restaurant. If you want to enhance the experience, you should order your favorite dish. You can enjoy the anticipation and the experience itself. However, you won’t create a new memory. It will simply blend in with all the other times you’ve ordered the same dish. If you want a new memory, order something you’ve never had before. It may be great or not – you can’t anticipate – but it will be more memorable.*

FOMO, of course, is the Fear of Missing Out, which seems to be an increasing concern in today’s society. Everything is accessible and we don’t want to miss any of it. Technologies such a mobile phones, video chat, and instant messages democratize our experience. We can share anything with anyone at any time. We won’t miss a thing.

But, of course, we do miss things. In fact, the very act of inserting technologies into our experiences makes us miss some of the experience. We’re fussing with our cameras rather than experiencing the action. We’re checking baseball scores rather than engaging with others. The desire to miss nothing causes us to miss something: the intensity of the present moment.

FOMO shifts our attention from the experiencing self to the remembering self. We take pictures, which helps us remember and share an experience. But the act of taking pictures insulates us from the experience itself. We’ve inserted technology between our experiences and ourselves.

As you can probably guess, I’m not the first person to suggest that FOMO mania actually causes us to miss much more than we realize. The tech and culture blogger, Anil Dash, coined the term JOMO — the Joy Of Missing Out – more than two years ago. Christina Crook wrote a book called The Joy of Missing Out and popularized the idea of Internet fasts. Sarah Wilson points out that FOMO has eradicated traditional boundaries that separated public time from private time. It used to be easy to spend a quiet evening at home. Now we need to declare an Internet fast to get some alone time.

Though it’s not a new idea, I suspect that the JOMO message needs some more evangelists. As a famous American once said: Be Here Now.

*I adopted the restaurant example from an episode of the Hidden Brain podcast called Hungry, Hungry Hippocampus.

Delayed Intuition – How To Hire Better

Daniel Kahneman is rightly respected for discovering and documenting any number of irrational human behaviors. Prospect theory – developed by Kahneman and his colleague, Amos Tversky – has led to profound new insights in how we think, behave, and spend our money. Indeed, there’s a straight line from Kahneman and Tversky to the new discipline called Behavioral Economics.

In my humble opinion, however, one of Kahneman’s innovations has been overlooked. The innovation doesn’t have an agreed-upon name so I’m proposing that we call it the Kahneman Interview Technique or KIT.

The idea behind KIT is fairly simple. We all know about the confirmation bias – the tendency to attend to information that confirms what we already believe and to ignore information that doesn’t. Kahneman’s insight is that confirmation bias distorts job interviews.

Here’s how it works. When we meet a candidate for a job, we immediately form an impression. The distortion occurs because this first impression colors the rest of the interview. Our intuition might tell us, for instance, that the candidate is action-oriented. For the rest of the interview, we attend to clues that confirm this intuition and ignore those that don’t. Ultimately, we base our evaluation on our initial impressions and intuition, which may be sketchy at best. The result – as Google found – is that there is no relationship between an interviewer’s evaluation and a candidate’s actual performance.

To remove the distortion of our confirmation bias, KIT asks us to delay our intuition. How can we delay intuition? By focusing first on facts and figures. For any job, there are prerequisites for success that we can measure by asking factual questions. For instance, a salesperson might need to be: 1) well spoken; 2) observant; 3) technically proficient, and so on. An executive might need to be: 1) a critical thinker; 2) a good strategist; 3) a good talent finder, etc.

Before the interview, we prepare factual questions that probe these prerequisites. We begin the interview with facts and develop a score for each prerequisite – typically on a simple scale like 1 – 5. The idea is not to record what the interviewer thinks but rather to record what the candidate has actually done. This portion of the interview is based on facts, not perceptions.

Once we have a score for each dimension, we can take the interview in more qualitative directions. We can ask broader questions about the candidate’s worldview and philosophy. We can invite our intuition to enter the process. At the end of the process, Kahneman suggests that the interviewer close her eyes, reflect for a moment, and answer the question, How well would this candidate do in this particular job?

Kahneman and other researchers have found that the factual scores are much better predictors of success than traditional interviews. Interestingly, the concluding global evaluation is also a strong predictor, especially when compared with “first impression” predictions. In other words, delayed intuition is better at predicting job success than immediate intuition. It’s a good idea to keep in mind the next time you hire someone.

I first learned about the Kahneman Interview Technique several years ago when I read Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast And Slow. But the book is filled with so many good ideas that I forgot about the interviews. I was reminded of them recently when I listened to the 100th episode of the podcast, Hidden Brain, which features an interview with Kahneman. This article draws on both sources.

Segmenting The Body Politic

As a marketing executive, I’m accustomed to the process of segmenting markets. My software companies divided markets by company size, SIC code, geography, and installed software. By doing so, we could identify and communicate with companies that were most likely to buy our products and services.

The Pew Research Center has done something similar with America’s body politic. Rather than two major political parties, Pew identifies eight different clusters of political thought and action: four for the Left and four for the Right. Let’s take a look at each. (Click here for the complete report and here for a Q&A on the methodology).

Among Conservatives

Core Conservatives support traditional Republican positions including smaller government and lower taxes. They also believe that the nation’s economic system is fundamentally fair. Core Conservatives generally support globalization, believing that the global economy creates opportunities for American businesses. This segment accounts for approximately 31% of all Republicans and roughly 13% of the American body politic.

Country First Conservatives are deeply concerned about immigration and generally believe that America should withdraw from the world. They strongly believe that the global economy is deeply threatening to American interests. More than any other segment, Country First Conservatives agree with the statement “If America is too open to people from all over the world, we risk losing our identity as a nation.” This segment accounts for 14% of Republicans and 6% of the American public.

Market Skeptic Republicans share many conservative values but are losing faith in the American economic system. They believe the economy unfairly favors powerful interests and are skeptical of banks and other financial institutions. More than any other group, the disagree with the statement “The U.S. economic system is generally fair to most Americans.” This segment accounts for 22% of Republicans and roughly 12% percent of the American public.

New Era Enterprisers form the most optimistic segment of either the Right or the Left. More than any other group they believe that the next generation of Americans will be better off than the current generation. New Era Enterprisers strongly support business and generally believe that immigrants strengthen the country. This segment makes up 17% of Republicans and 11% of the general public.

Adding it up (with some rounding errors), the four Conservative segments account for approximately 42% of the American body politic.

Among Liberals

Solid Liberals have liberal attitudes across the board. They overwhelmingly support government involvement in health insurance and government activism to ensure that blacks have equal rights with whites. They support government regulation of business and don’t believe one needs to be religious to be moral. Solid Liberals account for 16% of the general public 33% of Democrats.

Opportunity Democrats agree on many policy issues with Solid Liberals. They’re more likely, however, to be pro-business and to believe that most people can get ahead if they work hard. They comprise 12% of the general public and roughly 20% of Democrats.

Disaffected Democrats are positive about the Democratic Party but cynical about government in general. This is one of two minority-majority segments. They support activist government programs and believe that we should focus less on problems abroad and more on domestic issues. Disaffected Democrats account for 14% of the general public and 23% of Democrats.

Devout and Diverse is the second minority-majority segment. Like Disaffected Democrats, they face financial hardships. Among all the groups, this segment is the least politically engaged. They resist government regulation and strongly believe that one needs to believe in God to be moral. The Devout and Diverse account for 9% of the public and 11% of Democrats.

Adding it up, the four Liberal segments account for roughly 51% of the American body politic.

So if Conservatives account for 42% and Liberals for 51% of the general public, where are the rest of our voters? According to Pew, roughly 8% of the general public are Bystanders, described as a “relatively young, largely minority group” that is “missing in action politically”.

So where do you stand? Thanks to the Pew Research Center, you can now find out. Pew has published the Political Typology Quiz. Click here, answer a series of questions, and you can figure out which group most closely represents your worldview. I’ll be writing more about this in the future. You may want to know which group you’re in to follow along.

How To Save Democracy

Most historians would agree that the arts and sciences of persuasion – also known as rhetoric – originated with the Greeks approximately 2,500 years ago. Why there? Why not the Egyptians or the Phoenicians or the Chinese? And why then? What was going on in Greece that necessitated new rules for communication?

The simple answer is a single word: democracy. The Greeks invented democracy. For the first time in the history of the world, people needed to persuade each other without force or violence. So the Greeks had to invent rhetoric.

Prior to democracy, people didn’t need to disagree in any organized way. We simply followed the leader. We agreed with the monarch. We converted to the emperor’s religion. We believed in the gods that the priests proclaimed. If we disagreed, we were ignored or banished or killed. Simple enough.

With the advent of democracy, public life grew messy. We could no longer say, “You will believe this because the emperor believes it.” Rather, we had to persuade. The basic argument was simple, “You should believe this because it provides advantages.” We needed rules and pointers for making such arguments successfully. Socrates and Aristotle (and many others) rose to the challenge and invented rhetoric.

Democracy, then, is about disagreement. We recognize that we will disagree. Indeed, we recognize that we should disagree. The trick is to disagree without anger or violence. We seek to persuade, not to subdue. In fact, here’s a simple test of how democratic a society is:

What proportion of the population agrees with the following statement?

“Of course, we’re going to disagree. But we’ve agreed to resolve our disagreements without violence.”

It seems like a simple test. But we overlook it at our peril. Societies that can’t pass this test (and many can’t) are forever doomed to civil strife, violence, disruption, and dysfunction.

The chief function of rhetoric is to teach us to argue without anger. The fundamental questions of rhetoric pervade both our public and private lives. How can I persuade someone to see a different perspective? How can I persuade someone to agree with me? How can we forge a common vision?

Up through the 19th century, educated people were well versed in rhetoric. All institutions of higher education taught the trivium, which consisted of logic, grammar, and rhetoric. Having mastered the trivium, students could progress to the quadrivium – arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. The trivium provided the platform upon which everything else rested.

In the 20th century, we saw the rise of mass communications, government sponsored propaganda, widespread public relations campaigns, and social media. Ironically, we also decided that we no longer needed to teach rhetoric. We considered it manipulative. To insult an idea, we called it “empty rhetoric”.

But rhetoric also helps us defend ourselves against mass manipulation, which flourished in the 20th century and continues to flourish today. (Indeed, in the 21st century, we seem to want to hone it to an even finer point). We sacrificed our defenses at the very moment that manipulation surged forward. Having no defenses, we became angrier and less tolerant.

What to do? The first step is to revive the arts of persuasion and critical thinking. Essentially, we need to revive the trivium. By doing so, we’ll be better able to argue without anger and to withstand the effects of mass manipulation. Reviving rhetoric won’t solve the world’s problems. But it will give us a tool to resolve problems – without violence and without anger.

Managing Agreement: The Abilene Paradox.

I used to think it was difficult to manage conflict. Now I wonder if it isn’t more difficult to manage agreement.

A conflicted organization is fairly easy to analyze. The signs are abundant. You can quickly identify the conflicting groups as well as the members of each. You can identify grievances simply by talking with people. You can figure out who is “us” and who is “them”. Solving the problem may prove challenging but, at the very least, you know two things: 1) there is a problem; 2) its general contours are easy to see.

When an organization is in agreement, on the other hand, you may not even know that a problem exists. Everything floats along smoothly. People may not quiver with enthusiasm but no one is throwing furniture or shouting obscenities. Employees work and things get done.

The problem with an organization in agreement is that many participants actually disagree. But the disagreement doesn’t bubble up and out. There are at least two scenarios in which this happens:

- The Abilene Paradox – in the original telling, four members of a family in Coleman, Texas drove 53 miles to Abilene in a car without air conditioning in 104-degree heat to have dinner at a crummy diner. After driving 53 miles back, they ‘fessed up: not one of them had wanted to go. Each person thought the others wanted to go. They agreed to be agreeable. (A variant of this is known as the risky shift).

Similar paradoxes arise in organizations all the time. Each employee wants to be seen as a team player. They may have reservations about a decision but — because everyone else agrees or seems to agree — they keep quiet. Perhaps nobody agrees to a given project but they believe that everyone else does. Perhaps nobody wants to work on Project X. Nevertheless, Project X persists. Unlike a conflicted organization, nobody realizes that a problem exists.

- Fear – in organizations where failure is not an option, employees work hard to salvage success even from doomed projects. Admitting that a project has failed invites punishment. Employees happily throw good money after bad, hoping to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. Employees agree that failure must be delayed or hidden.

The second scenario is perhaps more dangerous but less common. A fear-based culture – if left untreated – will eventually corrupt the entire organization. Employees grow afraid of telling the truth. The remedy is easy to discern but hard to execute: the organization needs to replace executive management and create a new culture.

The Abilene paradox is perhaps less dangerous but far more common. Any organization that strives to “play as a team” or “hire team players” is at risk. Employees learn to go along with the team, even if they believe the team is wrong.

What can be done to overcome the Abilene paradox in an organization? Rosabeth Moss Kanter points out that there are two parts to the problem. First, employees make inaccurate assumptions about what others believe. Second, even though they disagree, they don’t feel comfortable speaking up. A good manager can work on both sides of the problem. Kanter suggests the following:

- Debates – include an active debate in all decision processes. Choose sides and formally air out the pros and cons of a situation. (I’ve suggested something similar in the decision by trial process).

- Assign devil’s advocates and give them the time and resources to develop a real position.

- Encourage organizational graffiti – I think of this as the electronic equivalent of Hyde Park’s Speaker’s Corner – a place where people can get things off their chests.

- Make confronters into heroes — even if you disagree with the message, reward the process.

- Develop a culture of pride – build collective self-esteem, not just individual self-esteem. We’re proud of what we have, including the right (or even the obligation) to disagree.

The activities needed to ward off the Abilene paradox are not draconian. Indeed, they’re fairly easy to implement. But you can only implement them if you realize that a problem exists. That’s the hard part.