Thinking, Feeling, Wanting

Wait! I’m thinking in German!

Yesterday, Suellen and I went to our yoga class, just like every other Monday morning for the past three years. We enjoy the class and especially like our teacher, Natasha. Unfortunately, Natasha wasn’t there.

Natasha had been called away on short notice so, without warning, we had a substitute. She swirled into the room, asking lots of questions about what we could and couldn’t do. Frankly, I wasn’t prepared and was a bit annoyed. Who was this person and why was she interrupting the routine that I was so comfortable with?

Though somewhat off balance, I thought about the three basic mental functions: thinking, feeling, wanting. Here’s how I was doing on each:

Feeling – I was feeling irritated and out of sync. My morning routine had been upset and I was barely even awake.

Wanting – I wanted Natasha to return and get things back to normal.

Thinking – I was thinking that the status quo was disrupted. Beyond that, I wasn’t thinking much. I was just feeling and wanting.

In my critical thinking class, we describe the thinking-feeling-wanting triad as our most basic mental functions. For me, feeling and wanting are deep down in the engine room of a big ship. The thinking system is the Captain’s bridge. When things are going well, the bridge controls the engine room.

Sometimes, however, the feeling/wanting system runs out of control and unhooks itself from the bridge. The engine room is running but nobody is steering the ship. Suellen calls this “getting your undies in a wad” and it’s a fairly common occurrence.

So, what to do when your undies are in a wad and the engine room is boiling over? (Yes, it’s a mixed metaphor). Too often we focus on what we’re feeling and wanting. The trick to regaining control is to return our attention to the thinking function. Feeling and wanting are about emotions, not about control. Only by returning to thinking can we regain a sense of control.

My go-to questions in such situations include, “Why am I feeling this way? Is it logical to feel this way? What assumptions am I making?” When I thought about these yesterday, my internal monologue went more or less like this:

I’m being biased. I don’t want anything to change. It’s the status quo bias. I like our Monday morning routine. It’s very comfortable. Change is uncomfortable. But it’s silly to be biased. Think about the opportunity. Change can be exciting. Get with the program.

I know that I’m describing a very minor disruption. Still, I think it’s instructive. The way to regain a measure of self-control is to understand the differences between feeling, wanting, and thinking. When your undies are in a wad, think about thinking.

By the way, we had a great yoga class.

(The engine room is better known as the limbic system. The bridge is the executive function. Just like the engine room and the bridge, the limbic system really is lower – physically and conceptually – than the executive function).

Are You The Boss Of Your Money?

Quick! Where’s my phone?

Several weeks ago, I asked the question, “Are You The Boss Of You?” and highlighted the many hidden factors that influence our thinking. We may think of ourselves as rock-ribbed, clear-headed, independent-minded thinkers but – in most cases – we’re not.

But even if you’re not the boss of you, might you still be the boss of your money? The simple answer is: probably not, at least not always. The longer answer is: it’s about to get worse.

Why wouldn’t you be the boss of your money? Because most of us don’t use money. Rather, we use substitutes that create physical, emotional, and psychological distance from our money. We don’t think of it as money; we think of it as credit.

Numerous writers and scholars have investigated the relationship between credit cards and consumer behavior. The relationship is sometimes subtle but the general thrust of the research is clear: credit cards cause us to spend more. Here are some examples:

- We’re more likely to leave a larger tip at a restaurant when paying by credit card than by cash.

- The credit card premium may be as much as 100%. In other words, people may pay up to twice as much when paying by credit card compared to paying by cash.

- We’re more likely to forget – or underestimate – how much we spent when paying by credit card.

- We’re likely to buy more unhealthy food when paying by credit card. Buying snacks is a classic impulse purchase. We’re less likely to follow our impulses when we pay with cash.

- Even financially sophisticated bankers and scholars make dubious decisions when using credit cards – especially when airline miles are involved.

- “How You Spend Affects How Much You Spend” – it’s the title of a research article but it’s also a good summary of the trend: if we spend anything other than cash, we’ll probably spend more.

Credit cards help us spend more because they remove us from the sense of cold, hard cash. Credit cards are elastic; they can expand to match our needs. Cash is anything but elastic – if you’re out, you’re out.

Why might the situation get worse? (Worse from a spender’s perspective; better from a seller’s perspective). Because we’re taking another step away from the tactile sensation of cash. The arrival of pay-by-phone systems adds more psychological distance between us and the world of hard-earned money.

With pay-by-phone systems we’re two steps away from cash. Step 1: We use the phone to pay for something. Step 2: We use a credit card to pay off the phone bill. Further, we can remove the physical nature of payments. With near field communications, we don’t even need to take the phone out of our pocket. We can just stand near the sensing device. It’s easier and more conceptual than reaching for your wallet.

So, is this a bad thing? Not necessarily. Credit helps the world go round. But it’s another example of how unseen influences can affect our behavior. I suspect that we’ll need to improve consumer education and teach more classes on critical thinking. In the meantime, I’m going to buy some junk food.

Should You Talk To Yourself?

Speak to me, wise one.

The way we think about the world comes from our body, not from our mind. If I like somebody, I might say, “I have warm feelings for her.” Why would my feelings be warm? Why wouldn’t I say, “I have orange feelings for her”? It’s probably because, when my mother held me as an infant, I was nice and toasty warm. I didn’t feel orange. I express my thoughts through metaphors that come from my body.

We all know that our minds affect our bodies. If I’m in a good mood mentally, my body may feel better as well. As I’ve noted before, the reverse is also true. It’s hard to stay mad if I force myself to smile.

The general field is referred to as metaphor theory or, more generally, as embodied cognition. Simply put, our bodies affect our thinking. Our brains are not digital computers, after all. They’re analog computers, using bodily metaphors to express our thoughts.

As it happens, I’ve used embodied cognition for years without realizing it. Before giving a big speech, I stand up straighter, flex my muscles, stretch out and up, and force myself to smile for 30 seconds. Then I’m ready. I didn’t realize it but I was practicing my bodily metaphors. I can speak more clearly (stand up straight), more powerfully (muscle flexing), and more cheerfully (smile), because of my warm-up routine.

My warm-up routine actually changes my hormones. As Amy Cuddy points out in her popular TED talk, practicing “power poses” for two minutes increases testosterone and reduces cortisol. The result is more dominance (testosterone) and less stress (cortisol). My body is priming me to give an exceptionally good speech. As Cuddy notes, it could also make me much more successful in a job interview.

I’m growing accustomed to the thought that the way I hold or move my body directly affects my thinking and mood. But what about my internal monologue? I talk to myself all the time. Is that a good thing? Do the words that I use in my monologue affect my thinking and behavior?

The answer is yes – for better and for worse. My “self-talk” affects how I perceive myself and that, in turn, affects how I behave. It’s also important how I address myself. Do I speak to myself in the first person – “I can do better than that.” Or do I speak to myself as someone else would speak to me – “Travis, you can do better than that.”

According to a recent article in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, the way I address myself makes a world of difference. If I speak as another person would address me, I gain more self-distance and perspective. I also reduce stress and make a better first impression. I can also give a better speech and will engage in “less maladaptive postevent processing”. (Whew!) In other words, I can perform better and feel better simply by choosing the right words in my internal monologue.

So, what’s it all mean? Take better care of your body to take better care of your mind. As my father used to say: “Look sharp, be sharp”. Oh… and watch your language.

(For an excellent article on how the field of embodied cognition has evolved, click here).

Coincidence? I Think Not.

Coincidence? I think not.

It’s a tough world out there so I start every day by reading the comics in our local newspaper. Comics and caffeine are the perfect combination to get the day started.

In our paper, the comics are in the entertainment section, which is usually either eight or twelve pages long. The comics are at the back. Last week, I pulled the entertainment section out, glanced at the first page, then flipped it open to the comics.

While I was reading my favorite comics, a random thought popped into my head: “I wonder if I could use Steven Wright’s comedy to teach any useful lessons in my critical thinking class?” Pretty random, eh?

Do you know Steven Wright? He’s an amazingly gifted comedian whose popularity probably peaked in the nineties. Elliot was a kid at the time and he and I loved to listen to Wright’s tapes. (Suellen was a bit less enthusiastic). Here are some of his famous lines:

- All those who believe in psychokinesis raise my hand.

- I saw a man with wooden legs. And real feet.

- I almost had a psychic girlfriend but she left me before we met.

- Everyone has a photographic memory. Some just don’t have film.

Given Wright’s ironic paraprosdokians, it seems logical that I would think of him as a way to teach critical thinking. But why would he pop up one morning when I was enjoying my coffee and comics?

I finished the comics and closed the entertainment section. On the back page, I spotted an article announcing that Steven Wright was in town to play some local comedy clubs. I was initially dumbfounded. I hadn’t seen the article before reading the comics. How could I have known? I reached an obvious conclusion: I must have psychic powers.

While congratulating myself on my newfound powers, I turned back to the front page of the entertainment section. Then my crest fell. There, in the upper left hand corner of the front page, was a little blurb: “Steven Wright’s in town.”

I must have seen the blurb when I glanced at the front page. But it didn’t register consciously. I didn’t know that I knew it. Rather, my System 1 must have picked it up. Then, while reading the comics, System 1 passed a cryptic note to my System 2. I had been thinking about my critical thinking class. When my conscious mind got the Seven Wright cue from System 1, I coupled it with what I was already thinking.

I wasn’t psychic after all. Was it a coincidence? Not at all. Was I using ESP? Nope. It was just my System 1 taking me for a ride. Let that be a lesson to us all.

(For more on System 1 versus System 2, click here and here and here).

Stress And The Nerve Curve

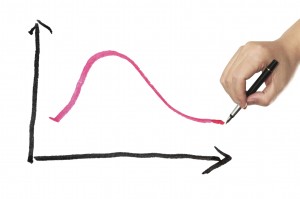

Nerve Curve.

When I coach an executive on public speaking, I always spend some time reviewing the nerve curve. This is a theoretical curve that plots degree of nervousness on one axis and presentation quality on the other.

The arc of the curve is the same as the arc of a baseball thrown across the diamond. It rises, reaches a peak, and then descends. The lesson is simple: you need to be somewhat nervous to give a good presentation. Nervousness alerts your senses, focuses your mind, and stiffens your spine – all good things for giving a great presentation.

If you follow the nerve curve, you’ll also realize that too much nervousness is a bad thing. The peak of the curve represents your best possible performance. If you become so nervous that you pass the peak, your performance starts to degrade. You might shake, sweat, and stammer. Your audience will be sympathetic; many of them have been there and done that. But they won’t be listening to your message.

Another way to read the nerve curve is that some stress is good for you. A little stress will improve your performance. Too much stress will degrade it. But it’s also true that too little stress will degrade your performance. If we want to maximize performance, being under-stressed may be just as bad as being overstressed.

That’s an interesting perspective for me because my docs have always told me to reduce my stress. They seemed to be saying that all stress – even a small amount – is bad for me. I should strive to eliminate stress. But striving creates stress, doesn’t it?

From my recent readings, I’m beginning to conclude that stress follows the nerve curve. Too little is bad for you; too much is bad for you. You need to attain just the right amount.

So, how do you attain the right amount? Well, not by disengaging from the world. If you try to minimize your stress, you may just get bored. And, as Colleen Merrifield and James Danckert point out in Experimental Brain Research, boredom is stressful. In fact, it may well be more stressful than being sad. (The authors also point out that, “Research on … boredom is underdeveloped.” Sounds like a promising field.)

Your attitude towards stress also seems to play an important role. If you believe that stress is bad for you, and you feel stressed out, you may well conclude that you might drop dead at any moment. That, in itself, is stressful. On the other hand, if you understand the nerve curve, you know that some stress is actually good for you. As you start feeling stressed, you’ll realize that your performance is also improving. You’re more likely to feel energized and engaged rather than stressed and depressed.

So, what’s the lesson here? Try a little stress. It may well be good for you.