Sunday Shorts – 7

Interesting stuff from this week and beyond.

Just what is the circular economy and are you ready for it? Reverse logistics anyone?

We’ve talked about design thinking versus systems thinking. What about manufacturing thinking? Can good design produce good manufacturing? Or is it the other way round?

Can your company overdo it on social media? There’s a good chance that you already are.

What personality type makes the best salespeople? It’s not the hard-charger. Or even the most outgoing. People with “moderate temperaments” make the most sales.

Dung beetles aren’t very smart. But they can navigate by the stars. Maybe they’re smarter than we thought.

Bleeding internally? Injecting a foam through your belly button could stop it. But you still need to go to the hospital.

Have the mid-January blues? Need a little excitement in your life? Here’s how to set your cocktails on fire.

Strategy: Five Components

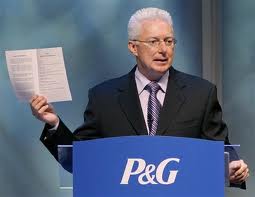

A.G Lafley is justifiably famous for taking over Procter & Gamble (P&G) and converting an insular company into a customer-centric, outward-looking culture known for a string of successful innovations. When Lafley became CEO in 2000, innovation was driven by thousands of in-house R&D designers, researchers, and engineers. They created neat stuff and “pushed” it to customers. Partially as a result, P&G’s success rate with new products and brands hovered around 15%. The R&D teams focused internally; only about 10% of new products came from outside the company.

Lafley essentially turned the company inside-out by putting the customer at the head of the innovation process. P&G called it Connect + Develop and emphasized collaboration with other departments, customers, and even outside research organizations. Lafley changed the culture from “not invented here” to “proudly found elsewhere”. P&G signed more than 1,000 collaborative agreements with outside organizations. It was a fundamental cultural change and the results were spectacular. According to a report from A.T. Kearney, “During Lafley’s tenure, sales doubled, profits quadrupled, and the company’s market value increased by more than $100 billion”.

Now Lafley has written a book, Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works, with Roger Martin, the Dean of the Rotman School of Management at the Univeristy of Toronto. Martin was Lafley’s “principal external strategy advisor”. In addition to Martin, Lafley built a brain trust of outside thinkers including designers and business professors. The eclectic nature of the group created many different “idea collisions” that generated process innovations as well as product innovations.

I’m sure that I’ll write a lot about the book in the future but it’s not quite out yet. It debuts in February. Today, I’m depending on the report from A.T. Kearney and a lengthy review from The Economist. One of the key insights is that P&G followed a strategy composed of five elements, each designed to help managers make the right decisions. These are:

- What does winning look like? What are we aiming for and what information do we look for along the way to help us understand if we’re making progress? Do we seek global domination, regional, or local?

- Which markets should we play in? Of course, this also implies another question: which markets should we ignore (or exit)? How do we determine which is which?

- How do we win? What’s our distinctive strategy in each market and category?

- What are our strengths and weaknesses and how do we deploy them in each market, against each competitor?

- What needs to be managed for the strategy to succeed? Of course, the inverse of this question is what doesn’t need to be managed? The Economist reports that one of Lafley’s “most important innovations was a slimmed-down strategy-review process … [that] replaced needlessly sprawling bureaucratic meetings….”

It’s a good story and an intriguing look at strategy. Unfortunately, it doesn’t have an entirely happy ending. The Economist reports that P&G has “stumbled badly” since Lafley left in 2009. Similarly, Martin’s consulting firm “got into financial difficulty and has been sold at a discount.” Still, the questions are relevant to any company’s strategy and the story is intriguing. I’ll report more soon.

Strategy: Who’s Number 2?

The CEO is clearly the most important executive when it comes to creating and implementing organizational strategy. Who’s the second most important executive for strategy?

The standard answer is probably the Chief Operation Officer — especially in terms of carrying out the strategy. But I’m starting to think that the COO is only the third or fourth most important strategic officer. So, who’s number 2? I’m leaning towards the head of Human Resources. Let’s call him or her the Chief Human Resources Officer or CHRO.

I’m leaning toward the CHRO because I’ve always believed that the soft stuff is hard. It’s not easy to get your culture right or to motivate employees for the long haul. It is all too easy to get your strategy crosswise with your culture. As I’ve noted before , when it’s culture versus strategy, culture always wins.

Similarly, I’ve never seen a company falter because they couldn’t find enough “numbers guys”. Our B-schools just keep churning them out. On the other hand, I have seen companies falter because they couldn’t find good communicators and motivators. Understanding human behavior is much more difficult than understanding the numbers. While we can teach people the “soft arts,” it doesn’t seem to be a popular specialty at university.

What’s really pushing me toward the CHRO as strategy leader is Scott Keller and Colin Price’s book, Beyond Performance: How Great Organizations Build Ultimate Competitive Advantage. (Click here for the book or here for a white paper). Keller and Price argue that too many companies pay close attention to performance (“the numbers”) but not nearly enough attention to organizational health. Their “…central message is that focusing on organizational health — the ability of your organization to align, execute, and renew itself faster than the competition — is just as important as focusing on the traditional drivers of business performance.” This has everything to do with the “people-oriented aspects of leading an organization.” In my mind, that means the CHRO better be intimately involved.

Keller and Price present a lot of statistical evidence to buttress their case. (They are McKinsey guys, after all). There is a distinct correlation between organizational health and organizational performance. They also present five “frames” for viewing both health and performance during transformation change: 1) Aspire; 2) Assess; 3) Architect; 4) Act; 5) Advance. I’ll write more about these in the future but the bottom line is that you need to use these frames to view both performance and health to develop a sustainable, high performance organization.

While I think the CRHO could and should be a strategy leader, in my experience, it doesn’t happen very often. I’ve seen HR organizations launch very interesting programs but, too often, the programs exist in their own right rather than as strategic enablers. They don’t impede the strategy but they don’t help it either. I also see the numbers guys set the strategy and then turn to the CHRO and say, in effect, “OK, here’s the strategy, now get us the people we need.” (In technology, this happens to CIOs all the time). To be effective, the CHRO really needs to be at the strategy table.

Why wouldn’t the CHRO be invited to the strategy table? Perhaps because they understand the soft stuff but not the business. I’ve seen CHROs (and CIOs) make naive comments in strategy meetings, showing that they clearly don’t understand the business. The result is a bunch of numbers guys rolling their eyeballs and looking vaguely embarrassed. Numbers guys need to learn more about the soft stuff. By the same token, CHROs (and their staffs) need to learn more about the performance side of the business. Perhaps then, they can truly become strategy leaders.

Skeptical Spectacles and the Saintliness Rule

Manti Te’o is a linebacker for Notre Dame and widely regarded as one of the best players in college football. During the past season, a story emerged that his girlfriend had leukemia and lingered near death. She died just before a big Notre Dame game. But Te’o was loyal to his teammates and played through his heartbreak to help Notre Dame win the game and go undefeated in the regular season.

It’s a great story. Unfortunately, it’s not true. The girlfriend never existed. The blogosphere has been obsessing over whether Te’o is the perpetrator or the victim of the hoax. I have a different question: why did we believe the story in the first place?

I think we were fooled by Te’o for the same reasons we were fooled by Lance Armstrong, Greg Mortenson, and Bernie Madoff. We were active participants in the deception. We wanted to believe their stories. I’m an avid cyclist and I certainly wanted to believe Armstrong’s story. What a great story it was. It gave us faith in our human ability to overcome great obstacles. So I fell prey to confirmation bias. Consciously and subconsciously, I attended to evidence that confirmed my beliefs. I ignored evidence that contradicted them. When Armstrong finally came clean, I felt he cheated me. I also realized I cheated myself. I had a double dose of regret.

Of course, there are people whose marvelous stories don’t need embellishment. Mother Teresa certainly comes to mind. She’s already beatified and seems well on her way to sainthood. Nelson Mandela was probably politically expedient from time to time but, by and large, the legend fits the man. Jackie Robinson wasn’t a perfect man but he really did do what he was famous for. (Hmm … why am I having difficulty identifying a contemporary white male to put in this category?)

So, how do we distinguish between those who claim to be saintly and those who actually are? Here’s my proposed Saintliness Rule. When a story makes someone sound saintly, put on your skeptical spectacles. Use your filters that help you suspend belief (as opposed to disbelief). Be patient, review the evidence, be doubtful. Be skeptical but not cynical. After all, there really are some saints out there.

Sunday Shorts – 6

Some interesting things I spotted this week, whether they were published this week or not.

Why not cover your body with paint that conducts electricity? Sounds like fun, no? And Matt Johnson, who is featured in this article, is a good buddy of our son, Elliot. Why wasn’t I invited to this party?

Can a $22,000 robot named Baxter help bring manufacturing back to America?

Can America’s leading experts on negotiation help break the impasse between Congress and the President? Here’s their best advice: high school kids could do better. (Click here).

Speaking of negotiation, is it possible to negotiate with Iran?

We’ve been doing hydraulic fracking in the U.S. since 1947. Are there any alternatives?

Want to shield yourself from facial recognition technologies? These glasses could help.

Sun in your eyes when you’re driving? Maybe a haptic steering wheel could help.

What do communication pros say is wrong with Lance Armstrong’s confession? He hasn’t yet expressed “remorse that feels genuine.” (Click here)

You know those little tiny hairs in your ears that convert sound waves to brain signals? When they die, they die — in humans at least. Other mammals can grow them back. A new drug therapy may be able to help us as well. (Click here). Maybe I can listen to Blue Oyster Cult again.