Innovation: Ideas That Generate Ideas

I’ve spent the past several days in the Minnesota woods at a client’s executive retreat. The client is a software company that has made a number of acquisitions over the past few years. A good portion of the discussion at the retreat focused on how to build a platform that can: 1) integrate the various acquisitions; 2) deliver a common interface; 3) simplify the support load; 4) provide a foundation for developing new functionality more quickly.

The discussion got me thinking about platforms — innovations that generate innovations. I’ve written a lot about innovation over the past year and especially the role of serendipity and mashup thinking. I’ve generally focused, however, on innovations as an end result. In other words, we adopt certain behaviors and modes of thinking and the result is an innovation. We then repeat the process and (hopefully) get another innovation. Creating the innovation essentially ends the process.

Platform thinking, on the other hand, can lead us to innovations that spawn innovations. As Steven Johnson points out, platforms abound in the natural world. Johnson builds an extended metaphor around the coral reef — a platform for unimaginably rich plant and animal life. Once the process gets started (in an otherwise barren sea), the reef builds a virtuous circle that attracts and facilitates multiple life forms. Part of the secret is collaboration. The CO2 that one animal gives off as waste becomes the building block for another animal’s home. Similarly, oxygen is a waste product for some reef denizens but the lifeblood of others.

In the human world, the Internet is probably the best recent example of a platform. The Internet creates both serendipity (we get to meet lots of people) and mashup thinking (we can easily find lots of new ideas to mash together). The Internet also takes care of a lot of the dirty work of information sharing. Just as the coral reef makes it easy for many animals to find a home, the Internet makes it easy for people like me to create websites and share information. We often hear the metaphor of researchers standing on the shoulders of giants. My website is standing on the shoulders of a very rich (and essentially free) technology stack.

Platform thinking is innovation taken to the next step. We think about how to create something that creates something. I’m generally a proponent of free markets, but Johnson makes as strong argument that the most fundamental platforms come from public agencies. Certainly, the Internet did not come from market-driven competition. Rather, it resulted from the collaboration of many specialists from many disciplines in an open environment. That’s pretty much like a coral reef.

So, what’s the next platform? I’m guessing that it’s a mashup of: 1) the human body, 2) secure communications, and 3) Internet sensors. We already have millions of Internet sensors monitoring the environment — everything from air pressure, to ocean salinity, to volcanic pressures. The next frontier could well be sensing human health conditions. We already have wearable condition monitors. For instance, friends of mine run a small company in Denver called Alcohol Monitoring. They provide a wearable device, with secure communications, that alerts probation officers when one of their wards has been drinking. Within a decade, I’d guess that health condition monitors will migrate from outside the body to inside the body. They’ll provide critical data that can help us foresee — and forestall — health crises. They’ll also provide a platform for a huge wave of new ideas, services, and fortunes. Sounds like a coral reef.

Circuses and Oceans

The first time we went to Cirque de Soleil, we took Elliot and a bunch of his 12-year-old buddies. After all, circuses are for kids, right? As it turned out, Suellen and I enjoyed the show just as much — maybe more — than the kids did. I didn’t expect that.

Cirque de Soleil is an excellent example of a mashup innovation. Traditional circuses were for kids. I remember going to Ringling Brothers with my folks. I was dazzled by Uno — the man who could do a handstand on one finger. My parents were troupers but I don’t think they were dazzled. They took me because … well, circuses are for kids.

On the other hand, Broadway musicals are from grownups. They have a bit of a story to follow, they have some conflict, perhaps some mushy stuff, and a resolution. Most of all they have singing. This is where young kids start squirming. I mean, really … how many seven-year-olds want to know that when you’re a Jet, you’re Jet all the way?

The genius of Cirque de Soleil is that it mashes up the traditional circus — get the kids — with Broadway musicals — bring the grownups, too. There’s enough of a story to appeal to Mom and Dad and enough cool (and weird) stuff to appeal to seven-year-olds. It’s family entertainment for modern city dwellers.

While Cirque is a great mashup story, it may be more than that. According to W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne, it’s also a great example of a Blue Ocean Strategy. For Kim and Mauborgne, there are red oceans and blue oceans. A red ocean is full of the blood of competitive strife — it’s red in tooth and claw. The red ocean represents a market of a given size. It’s not going to get any bigger so the only way for one company to grow is to make another company shrink. Strategy is all about defeating the competition rather than winning the customer. As Kim and Mauborgne point out, the market for traditional circuses was very much a red ocean.

A blue ocean, on the other hand, allows you to jump beyond the competition. You create something new and, in doing so, you create a new market where your traditional competitors are irrelevant. The authors offer some great examples of blue ocean strategies and some intriguing and very instructive tips for how to develop one. For Kim and Mauborgne, the genius of Cirque de Soleil is that they have leapt out of the red ocean and into a blue ocean where they rule the waves. Indeed, they’re the only ship in sight.

I’ll report on more blue ocean examples in future posts. At the same time, however, I have a nagging feeling that a blue ocean is not that different from the classic marketing strategy of creating a new category. Once upon a time, for instance, sedans were practical but not much fun to drive. (For my British readers, what Americans call a sedan, you call a saloon). On the other hand, sports cars were fun to drive but not very practical. Then BMW mashed up the two categories and created a sports sedan — practical yet fun to drive. Was the BMW sports sedan a new category or a blue ocean? I’ll report more on that in the future. No matter what you call it, however, mashups are a great way to get there.

Strategy: Five Components

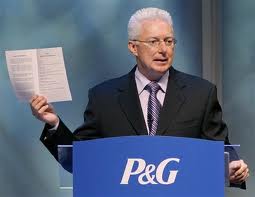

A.G Lafley is justifiably famous for taking over Procter & Gamble (P&G) and converting an insular company into a customer-centric, outward-looking culture known for a string of successful innovations. When Lafley became CEO in 2000, innovation was driven by thousands of in-house R&D designers, researchers, and engineers. They created neat stuff and “pushed” it to customers. Partially as a result, P&G’s success rate with new products and brands hovered around 15%. The R&D teams focused internally; only about 10% of new products came from outside the company.

Lafley essentially turned the company inside-out by putting the customer at the head of the innovation process. P&G called it Connect + Develop and emphasized collaboration with other departments, customers, and even outside research organizations. Lafley changed the culture from “not invented here” to “proudly found elsewhere”. P&G signed more than 1,000 collaborative agreements with outside organizations. It was a fundamental cultural change and the results were spectacular. According to a report from A.T. Kearney, “During Lafley’s tenure, sales doubled, profits quadrupled, and the company’s market value increased by more than $100 billion”.

Now Lafley has written a book, Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works, with Roger Martin, the Dean of the Rotman School of Management at the Univeristy of Toronto. Martin was Lafley’s “principal external strategy advisor”. In addition to Martin, Lafley built a brain trust of outside thinkers including designers and business professors. The eclectic nature of the group created many different “idea collisions” that generated process innovations as well as product innovations.

I’m sure that I’ll write a lot about the book in the future but it’s not quite out yet. It debuts in February. Today, I’m depending on the report from A.T. Kearney and a lengthy review from The Economist. One of the key insights is that P&G followed a strategy composed of five elements, each designed to help managers make the right decisions. These are:

- What does winning look like? What are we aiming for and what information do we look for along the way to help us understand if we’re making progress? Do we seek global domination, regional, or local?

- Which markets should we play in? Of course, this also implies another question: which markets should we ignore (or exit)? How do we determine which is which?

- How do we win? What’s our distinctive strategy in each market and category?

- What are our strengths and weaknesses and how do we deploy them in each market, against each competitor?

- What needs to be managed for the strategy to succeed? Of course, the inverse of this question is what doesn’t need to be managed? The Economist reports that one of Lafley’s “most important innovations was a slimmed-down strategy-review process … [that] replaced needlessly sprawling bureaucratic meetings….”

It’s a good story and an intriguing look at strategy. Unfortunately, it doesn’t have an entirely happy ending. The Economist reports that P&G has “stumbled badly” since Lafley left in 2009. Similarly, Martin’s consulting firm “got into financial difficulty and has been sold at a discount.” Still, the questions are relevant to any company’s strategy and the story is intriguing. I’ll report more soon.

Round the Clock Healthcare — for Free?

When I go on a long bike ride, I usually wear a heart monitor. I like to know how hard my ticker is tocking. I also carry a smartphone with GPS in it. I like to know where I am … and where the nearest hospital is.

Let’s do a little mashup thinking. What if my heart monitor were connected to the phone and GPS? Here’s a scenario: the heart monitor notices that my heart is going haywire. It sends a signal to the phone. The phone uses GPS to locate the nearest hospital, sends an emergency call (perhaps using Amcom Mobile Connect*), along with my location. The hospital dispatches an ambulance to my GPS location to pick me up. It could save my life. And it’s all based on currently available technologies. All we have to do is mash them up.

A few weeks ago I wrote a post about how a strategist might think about healthcare costs. All the experts say that healthcare costs are bound to go up. In my experience, when all the experts point in one direction, it’s always useful to look in the other direction — just to make sure.

Several of my friends let me know that I was wrong — healthcare costs will continue to rise, if for no other reason than the government is involved. That wasn’t really my point. I was merely trying to illustrate strategic thinking. But now I am thinking about healthcare costs and I wonder if new technologies won’t have a huge impact. By and large, many of those technologies are already available. We just need to mash them up.

Here’s a simple example — the HAPIfork, which was introduced at this year’s Consumer Electronic Show (CES). The HAPIfork mashes up a fork, a timer, and (perhaps) an accelerometer to keep track of how fast you’re eating. HAPIfork measures the number of “fork servings per minute” and loads the data to a dashboard on your smartphone. You can keep track of how fast you’re eating. Apparently, eating slowly is better for you. You can adjust your behavior to be healthier.

I don’t think HAPIfork is going to revolutionize healthcare – but it hints at things to come. As the internet of things evolves, we’ll connect more and more sensors to monitor the word around us. We’ll also monitor our health with sensors that can inform us more precisely of our own condition. Am I getting dehydrated? Is my blood pressure up? Do I need to take corrective actions? A connected sensor could also alert my physician to potential trouble. Imagine, for instance, an internet toilet that uses chemical sensors to monitor your, um, output. If something is out of whack it lets you know. If something is really out of whack it lets your physician know.

Could connected healthcare reduce our costs in the long run? The real answer is that nobody knows. But it’s a question worth asking and technology worth pursuing. It’s an “unforeseen” solution that could just prove the experts wrong.

* I consult to Amcom and, yes, this is a shameless attempt to generate publicity for one of my clients.