Ebola and Availability Cascades

We can’t see it so it must be everywhere!

Which causes more deaths: strokes or accidents?

The way you consider this question speaks volumes about how humans think. When we don’t have data at our fingertips (i.e., most of the time), we make estimates. We do so by answering a question – but not the question we’re asked. Instead, we answer an easier question.

In fact, we make it personal and ask a question like this:

How easy is it for me to retrieve memories of people who died of strokes compared to memories of people who died by accidents?

Our logic is simple: if it’s easy to remember, there must be a lot of it. If it’s hard to remember, there must be less of it.

So, most people say that accidents cause more deaths than strokes. Actually, that’s dead wrong. As Daniel Kahneman points out, strokes cause twice as many deaths as all accidents combined.

Why would we guess wrong? Because accidents are more memorable than strokes. If you read this morning’s paper, you probably read about several accidental deaths. Can you recall reading about any deaths by stroke? Even if you read all the obituaries, it’s unlikely.

This is typically known as the availability bias – the memories are easily available to you. You can retrieve them easily and, therefore, you overestimate their frequency. Thus, we overestimate the frequency of violent crime, terrorist attacks, and government stupidity. We read about these things regularly so we assume that they’re common, everyday occurrences.

We all suffer from the availability bias. But when we suffer from it simultaneously and together, it can become an availability cascade – a form of mass hysteria. Here’s how it works. (Timur Kuran and Cass Sunstein coined the term availability cascade. I’m using Daniel Kahneman’s summary).

As Kahneman writes, an “… availability cascade is a self-sustaining chain of events, which may start from media reports of a relatively minor incident and lead up to public panic and large-scale government action.” Something goes wrong and the media reports it. It’s not an isolated incident; it could happen again. Perhaps it could affect a lot of people. Perhaps it’s an invisible killer whose effects are not evident for years. Perhaps you already have it. How would one know? Or perhaps it’s a gruesome killer that causes great suffering. Perhaps it’s not clear how one gets it. How can we protect ourselves?

Initially, the story is about the incident. But then it morphs into a meta-story. It’s about angry people who are demanding action; they’re marching in the streets and protesting in front of the White House. It’s about fear and loathing. Then experts get involved. But, of course, multiple experts never agree on anything. There are discrepancies in the stories they tell. Perhaps they don’t know what’s really going on. Perhaps they’re hiding something. Perhaps it’s a conspiracy. Perhaps we’re all going to die.

A story like this can spin out of control in a hurry. It goes viral. Since we hear about it every day, it’s easily available to our memories. Since it’s available, we assume that it’s very probable. As Kahneman points out, “…the response of the political system is guided by the intensity of public sentiment.”

Think it can’t happen in our age of instant communications? Go back and read the stories about ebola in America. It’s a classic availability cascade. Chris Christie, the governor of New Jersey, reacted quickly — not because he needed to but because of the intensity of public sentiment. Our 24-hour news cycle needs something awful to happen at least once a day. So availability cascades aren’t going to go away. They’ll just happen faster.

Are We Done Yet?

Is it done yet?

A few years ago, I asked some artist friends, “How do you know when a painting is finished?” By and large, the answers were vague. There’s certainly no objective standard. Answers included, “It’s a feeling…” or “I know it when I see it.” One friend confessed that, when she sees one of her paintings hanging in a friend’s house – even years after she “finished” it – she’s tempted to take out her brushes and continue the process. The simplest, clearest answer I got was, “I know it’s done when I run out of time.”

I thought of my artist friends the other night when I heard Jennifer Egan give a lecture at the Pen and Podium series at the University of Denver. Egan, who won a Pulitzer Prize for her novel, A Visit From The Goon Squad, spoke mainly about her craft – how she develops her ideas, characters, and plots. While she’s probably best known for her novels, Egan also writes long-form nonfiction, mainly for the New York Times Magazine.

Interestingly, Egan uses different writing processes for fiction and nonfiction. For nonfiction, she uses a keyboard. For fiction, she writes it out longhand. She said, “I write my fiction quickly and in longhand because I want to write in an unthinking way.” It sounds to me that she writes her fiction from System 1 and her nonfiction from System 2. I wonder how common that is. Do most authors who compose fiction, write from System 1? Do authors of nonfiction typically write from System 2? (For the record, I write nonfiction and I write in System 2; I’m not sure how to write from System 1).

Egan went on to say that she follows a simple three-step process in her writing: “Write quickly. Write badly. Fix it.” She captures the essence of her idea quickly and then revisits it to clean and clarify her thoughts. I wonder how she knows when she’s finished.

I thought of Egan the other day when I was reading about Google’s management culture. One of Google’s mottos is, “Ship then iterate.” The general idea is to get the software into reasonably good shape and then ship it to customers. (You may want to call it a beta version). Once the software is in customer hands, you’ll find out all kinds of interesting things. Then you iterate with a new release that adds new features or fixes old ones. The point is to do it quickly and do it frequently. It sounds remarkably similar to Jennifer Egan’s writing process.

There’s a corollary to this, of course: your first draft or first release is not going to be very good. Egan told the story of the first draft of her first novel. It was so bad, even her mother wouldn’t return her calls. In the software world, we say something quite similar, “If you’re proud of your first release, you shipped it too late.”

Software, of course, is never finished. You can always do something more (or less). I wonder if the same isn’t true of every work of art. There’s always something more.

While you could always do something more, the trick is to get the first draft done quickly. Create it quickly. Think about it. Fix it. Repeat. It’s a good way to create great things.

Now You See It, But You Don’t

What don’t you see?

The problem with seeing is that you only see what you see. We may see something and try to make reasonable deductions from it. We assume that what we see is all there is. All too often, the assumption is completely erroneous. We wind up making decisions based on partial evidence. Our conclusions are wrong and, very often, consistently biased. We make the same mistake in the same way consistently over time.

As Daniel Kahneman has taught us: what you see isn’t all there is. We’ve seen one of his examples in the story of Steve. Kahneman present this description:

Steve is very shy and withdrawn, invariably helpful but with little interest in people or in the world of reality. A meek and tidy soul, he has a need for order and structure, and a passion for detail.

Kahneman then asks if it’s more likely that Steve is a farmer or a librarian?

If you read only what’s presented to you, you’ll most likely guess wrong. Kahneman wrote the description to fit our stereotype of a male librarian. But male farmers outnumber male librarians by a ratio of about 20:1. Statistically, it’s much more likely that Steve is a farmer. If you knew the base rate, you would guess Steve is a farmer.

We saw a similar example with World War II bombers. Allied bombers returned to base bearing any number of bullet holes. To determine where to place protective armor, analysts mapped out the bullet holes. The key question: which sections of the bomber were most likely to be struck? Those are probably good places to put the armor.

But the analysts only saw planes that survived. They didn’t see the planes that didn’t make it home. If they made their decision based only on the planes they saw, they would place the armor in spots where non-lethal hits occurred. Fortunately, they realized that certain spots were under-represented in their bullet hole inventory – spots around the engines. Bombers that were hit in the engines often didn’t make it home and, thus, weren’t available to see. By understanding what they didn’t see, analysts made the right choices.

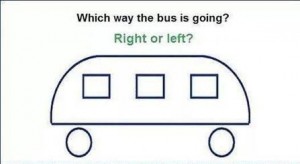

I like both of these examples but they’re somewhat abstract and removed from our day-to-day experience. So, how about a quick test of our abilities? In the illustration above, which way is the bus going?

Study the image for a while. I’ll post the answer soon.

Observation and Innovation

Don’t be cowed.

In the mid-1790s, an English country doctor named Edward Jenner made a rather routine observation: milkmaids don’t get smallpox. Milkmaids were often exposed to cowpox, a disease that’s related to smallpox but much less deadly. Cowpox gave the milkmaids flu-like symptoms that were distressing but certainly not lethal. Jenner guessed that the cowpox also conferred immunity to smallpox.

Jenner wasn’t the first to observe the cowpox effect but he was the first in the western world to act on his hunch. He created a vaccine from the scraping of cowpox pustules and administered it to some two-dozen people. They all acquired the immunity to smallpox. Jenner conducted experiments to demonstrate the treatment’s efficacy as well as the biological mechanisms in play. As a result, he is often described as the father of modern immunology.

Jenner’s breakthrough came from simple observation. He paid close attention to the world around him, observed an anomaly, and acted on it. Observation provides a foundation for both critical thinking and innovation. If necessity is the mother of invention, then observation is the grandmother. One has to observe the necessity in order to address it. (If a necessity happens in the forest and no one observes it, is it really necessary?)

How does one learn to be a good observer? Interestingly, most critical thinking textbooks don’t address this. Rather, they teach readers how to ask insightful, clarifying questions. That’s useful, of course, but also somewhat limited. Observation is merely a continuation of questioning by other means. Much more than questioning, observation can reveal fundamental insights that produce important innovations – like Jenner’s.

How does one become a good observer? Here are some thoughts I’ve gleaned from reading and from my own experience.

Pay attention – this may seem obvious but it’s hard to do. We’ve all had the experience of driving somewhere and not remembering how we got there. The mind wanders. What to do? Remind yourself to stay in the moment. Make mental notes. Ask yourself why questions. Mindfulness training may help.

Keep a journal – you can’t observe everything a given moment. Observations grow and change over time. You may have half a good idea today. The other half may not occur to you for years. Steve Johnson calls it a slow hunch. The trick to a slow hunch is remembering the first half. If it’s written down, it’s much easier to recall. (Indeed, one of the reasons I write this blog is to remember what I’ve learned).

Slow down – it’s much easier to think clearly and observe effectively if you take your time. The pace of change may well be accelerating but accelerating your thinking is not going to help you.

Pay attention to System 1 – your fast, automatic system knows what the world is supposed to be like. It can alert you to anomalies that System 2 doesn’t recognize.

Enhance your chance by broadening your horizons – Pasteur said, “Chance favors only the prepared mind.” You can prepare your mind by reading widely and by interacting with people who have completely different experiences than yours. Diversity counts.

Look for problems/listen to complaints – if a person is having a problem with something, it creates an opportunity to fix it.

Test your hypothesis – in other words, do something. Your hypothesis may be wrong but you’ll almost certainly learn something by testing it.

Observing is not always easy but it is a skill that can be learned. Many of the people we call geniuses are often superb observers more than anything else. Like Edward Jenner.

Postscript – Jenner inoculated his first patient in May 1796. Once Jenner showed its efficacy, the treatment spread quickly. So did opposition to it. In 1802, James Gillray, a popular English caricaturist, created the illustration above. Opponents claimed that cows would grow out of the bodies of people who received cowpox vaccines. Anti-vaccine agitation has been entwined with public health initiatives since the very beginning.

Two Brains. So What?

Alas, poor System 1…

We have two different thinking systems in our brain, often called System 1 and System 2. System 1 is fast and automatic and makes up to 95% of our decisions. System 2 is a slow energy hog that allows us to think through issues consciously. When we think of thinking, we’re thinking of System 2.

You might ask: Why would this matter to anyone other than neuroscientists? It’s interesting to know but does it have any practical impact? Well, here are some things that we might want to change based on the dual-brain idea.

Economic theory – our classic economic theories depend on the notion of rational people making rational decisions. As Daniel Kahneman points out, that’s not the way the world works. For instance, our loss aversion bias pushes us towards non-rational investment decisions. (See also here). It happens all the time and has created a whole new school of thought called behavioral economics (and a Nobel prize for Kahneman).

Intelligence testing – System 1 makes up to 95% of our decisions but our classic IQ tests focus exclusively on System 2. That doesn’t make sense. We need new tests that incorporate rationality as well as intelligence.

Advertising – we often measure the effectiveness of advertising through awareness tests. Yet System 1 operates below the threshold of awareness. We can know things without knowing that we know them. As Peter Steidl points out, if we make 95% of our decisions in System 1, doesn’t it also follow that we make (roughly) 95% of our purchase decisions in System 1? Branding should focus on our habits and memory rather than our awareness.

Habits (both good and bad) – we know that we shouldn’t procrastinate (or smoke or eat too much, etc.). We know that in System 2, our conscious self. But System 2 doesn’t control our habits; System 1 does. In fact, John Arden calls System 1 the habitual brain. If we want to change our bad habits (or reinforce our goods ones), we need to change the habits and rules stored in System 1. How do we do that? Largely by changing our memories.

Judgment, probability, and public policy – As Daniel Kahneman points out, humans are naturally good at grammar but awful at statistics. We create our mental models in System 1, not System 2. How frequently does something happen? We estimate probability based on how easy it is to retrieve memories. What kinds of memories are easy to retrieve? Any memory that’s especially vivid or scary. Thus, we overestimate the probability of violent crime and underestimate the probability of good deeds. We make policy decisions and public investments based on erroneous – but deeply held – predictions.

Less logic, louder voice – people who aren’t very good at something tend to overestimate their skills. It’s the Dunning-Kruger effect – people don’t recognize their own ineptitude. It’s an artifact of System 1. Experts will often craft their conclusions very carefully with many caveats and warnings. Non-experts don’t know that their expertise is limited; they simply assume that they’re right. Thus, they often speak more loudly. It’s the old saying: “He’s seldom right but never in doubt”.

Teaching critical thinking – I’ve read nearly two-dozen textbooks on critical thinking. None of them give more than a passing remark or two on the essential differences between System 1 and System 2. They focus exclusively on our conscious selves: System 2. In other words, they focus on how we make five per cent of our decisions. It’s time to re-think the way we teach thinking.