Donald, Bernie, and Belittlement

Singing from the same hymnal.

What do Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump have in common?

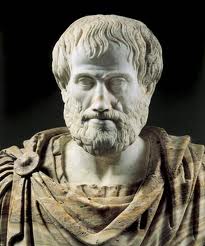

In addition to being old, white, and angry, they both use an ancient rhetorical technique known as attributed belittlement. The technique has survived at least since the days of Aristotle. It survives because it’s simple and effective.

Attributed belittlement works because nobody likes to be humiliated. If I tell you that Joe thinks you’re a low-life, no-account, I’ll probably get a rise out of you. What I say about Joe may not be true, but that’s not the point. I want you to feel humiliated. To accomplish that, I’ve attributed to Joe belittling thoughts about you. I want to make you so angry that you don’t even think about whether I’m telling the truth. I want to manipulate you into focusing your anger on Joe. I want to short-circuit your critical thinking apparatus.

The technique works even better with groups than with individuals like Joe. You can get to know an individual. Perhaps you already know Joe and you like him. That casts doubt on my veracity. But with a group – nameless, faceless bureaucrats, for instance – it’s easy to imagine the worst. They hate us. They look down on us. They take advantage of us. Belittlement works best when we can profile an entire group of people. It’s not logical but it’s effective.

So, let’s imagine the following quote:

They look down on you. They think they’re superior to you. They think you’re here to serve them. They think they can push you around. They’ve taken your jobs and your money and now they just want to rub your nose in it.

Would this quote come from Donald or Bernie? Well, … it depends on who “they” are. If we’re talking about immigrants and religious minorities, it seems like something the Donald would say. If, on the other hand, we’re talking about billionaires and fat cats, it’s more likely something that Bernie would say.

Note the rhetorical device. While talking to you, the speaker attributes horrible thoughts to other people. These are people who are easy to caricature. They’re also easy to profile: after all, they all think alike, don’t they? They’re also not here to defend themselves. Whether you’re Donald or Bernie, it’s an easy way to score cheap points.

By the way, I’m not an innocent bystander here. I sold software for mid-sized companies and often competed against some very big fish. I told prospective customers that, “The big software companies don’t want your business. You don’t generate enough revenue. They won’t give their best service. You’re just a little fish in a big pond.” It didn’t work every time. But when it did, it worked very well.

The good thing about attributed belittlement is that it’s easy to spot. Someone is talking to you about another group or company or person who is not physically present. The speaker attributes belittling thoughts to the third party. It’s a good time to say, “Hey, wait a minute! You’re using attributed belittlement to make me angry. You must think I’m stupid.”

The Mother Of All Fallacies

An old script, it is.

How are Fox News and Michael Moore alike?

They both use the same script.

Michael Moore comes at issues from the left. Fox News comes from the right. Though they come from different points on the political spectrum, they tell the same story.

In rhetoric, it’s called the Good versus Evil narrative. It’s very simple. On one side we have good people. On the other side, we have evil people. There’s nothing in between. The evil people are cheating or robbing or killing or screwing the good people. The world would be a better place if we could only eliminate or neuter or negate or kill the evil people.

We’ve been using the Good versus Evil narrative since we began telling stories. Egyptian and Mayan hieroglyphics follow the script. So do many of the stories in the Bible. So do Republicans. So do Democrats. So do I, for that matter. It’s the mother of all fallacies.

The narrative inflames the passions and dulls the senses. It makes us angry. It makes us feel that outrage is righteous and proper. The narrative clouds our thinking. Indeed, it aims to stop us from thinking altogether. How can we think when evil is abroad? We need to act. We can think later.

I became sensitized to the Good versus Evil narrative when I lived in Latin America. I met more than a few people who are convinced that America is the embodiment of evil. They see it as a country filled with greedy, immoral thieves and murderers who are sucking the blood of the innocent and good people of Latin America. I had a difficult time squaring this with my own experiences. Perhaps the narrative is wrong.

Rhetoric teaches us to be suspicious when we hear Good versus Evil stories. The word is a messy, chaotic, and random place. Actions are nuanced and ambiguous. People do good things for bad reasons and bad things for good reasons. A simple narrative can’t possibly capture all the nuances and uncertainties of the real world. Indeed, the Good versus Evil doesn’t even try. It aims to tell us what to think and ensure that we never, ever think for ourselves.

When Jimmy Carter was elected president, John Wayne attended his inaugural even though he had supported Carter’s opponent. Wayne gave a gracious speech. “Mr. President”, he said, “you know that I’m a member of the loyal opposition. But let’s remember that the accent is on ‘loyal’”. How I would love to hear anyone say that today. It’s the antithesis of Good versus Evil.

Voltaire wrote that, “Anyone who has the power to make you believe absurdities has the power to make you commit injustices.” The Good versus Evil narrative is absurd. It doesn’t explain the world; it inflames the world. Ultimately, it can make injustices seem acceptable.

The next time you hear a Good versus Evil story, grab your thinking cap. You’re going to need it.

(By the way, Tyler Cowen has a terrific TED talk on this topic that helped crystallize my thinking. You can find it here.)

Let’s Make Better Mistakes Tomorrow

History teaches us nothing.

What does it mean when the entire country is talking in the past tense? For me, it means I’m worried and dispirited.

As the Greeks taught us, arguments in the past tense are about blame. We’re trying to find out who did what, when, and how. That’s important in a judicial process when we’re trying to assess guilt or innocence. Otherwise, I’m convinced that arguing in the past tense is useless. We learn nothing. We solve nothing. We change nothing.

Politicians, of course, are eager to lay blame. Blame leads to anger and anger leads to votes. It works and has always worked, so politicians will never change the basic formula – blame the other guy, fire up the base, and garner some votes. It’s not about logic or even hope for the future. It’s about pandering and identity.

Some people argue that we can learn important lessons from the past. I’m wondering when that will happen. We make the same mistakes over and over. The mere fact that we think we’ve learned lessons from the past may actually make us more dangerous. We think we’re all the wiser; we couldn’t possibly make those mistakes again. We grow self-satisfied and egocentric. Egocentrism is the reason why every person has to make her own mistakes. We don’t realize we’re egocentric until it’s too late.

Other people argue that things happen for a reason. If we can only divine those reasons, we can understand the arc and thrust of history. But there are so many possible reasons for any given action, we can marshal evidence for virtually any argument. What caused the Civil War (or was it the War Between The States)? It was slavery. No, it was industrialization. No, it was Lincoln’s perfidy. It was the North’s fault. No, it was the South’s fault. In the end, do we really know? Are we any wiser? Perhaps we just look for the “facts” that we already believe. It’s confirmation bias writ large.

Mark Twain said it well, ““In the real world, the right thing never happens in the right place and the right time. It is the job of journalists and historians to make it appear that it has.” We can write history any way we want. We have a near infinite number of ways to interpret a story. We see this in fiction regularly. Just watch The Affair on Showtime. Or read La Maison de Rendez-Vous. Or watch Rashomon. Perhaps history is just a branch of fiction in which we use real people.

So, what’s the cure? First, let’s stop thinking about the past. Every good financial analyst will tell you not to consider sunk costs as you make decisions about future investments. Sunk costs are just that – they’re sunk. So is history. No use crying over spilt milk.

Second, let’s take a cue from design thinking. Instead of analyzing the problem, let’s analyze the solution. Let’s look forward and imagine a solution. Then let’s ask, how do we get there? It won’t work perfectly. In fact, it may not work at all. But at least it has a chance. History doesn’t. As they say, let’s make better mistakes tomorrow.

Chris Christie: The I Guy

Me, myself, and I

In my video, Five Tips for the Job Interview, my first tip is to be careful how often you say “I” as opposed to “we”. If the company you’re interviewing with is looking for team players — and many companies say they are — then saying “I” too often can hurt your chances. You can come across as self-centered and egocentric. Someone, in other words, who doesn’t play well with others.

I thought about this tip the other day when I watched Chris Chrstie’s press conference addressing the bridge closure scandal. (If you haven’t heard about it, you can get a good summary here). As the Republican governor of a very Democratic New Jersey, Chritsie is widely regarded as an appealing candidate for the Republican nomination for president in 2016. In a way, he’s interviewing for the biggest job of all. Perhaps he should have watched my video.

In the press conference, Christie needed to address a scandal that appears to be about naked political payback. The Democratic mayor of Fort Lee, New Jersey didn’t endorse Christie for governor in the recent campaign. As a result (it appears), Christie’s minions shut down traffic in Fort Lee for four days. Christie needed to apologize and distance himself from such nasty political deeds.

Dana Milbank, a columnist for the Washington Post, paid close attention to the press conference. In fact, he went through the transcript and analyzed Christie’s language. The press conference lasted 108 minutes; Christie said some form of “I” or “me” (I, I’m, I’ve, me, myself) 692 times. That’s 6.4 times per minute or a little more than once every ten seconds.

The net result is that Christie comes across as an egomaniac. That may be the case but, generally, you don’t want to come across that way in an important interview. There’s a lot that I like about Governor Christie — he seems to be one of the few politicians in America who can actually pronounce the word “bipartisan”. I hope he can learn to pronounce “we” and “you” as well.

Aristotle, HBR, and Me

I love it when the Harvard Business Review agrees with me. A recent HBR blog post by Scott Edinger focuses on, “Three Elements of Great Communication, According to Aristotle“. The three are: ethos, logos, and pathos.

Ethos answers the questions: Are you credible? Why should I trust your recommendations? Logos is the logic of your argument. Is it factual? Do you have the evidence to back it up? (Interestingly, the more ethos you have,the less evidence you need to back up your logos. People will trust that you’re credible). Pathos is your ability to connect emotionally with your audience. If you have high credibility and impeccable logic, your audience might conclude that you could take advantage of them. Pathos reassures them that you won’t — your audience knows that you’re a good citizen.

When I teach people the arts of public speaking, I generally recommend that they start by establishing their credibility (ethos). The trick is to do this without overdoing it. If you come across as a braggart, you reduce your credibility rather than burnishing it. A good tip to remember is to use the word, “we” rather than “I”. “We” implies teamwork; “I” implies an egocentric psychopath.

After establishing your credibility, you proceed to the logic (logos) of your argument. What is it that you’re recommending and why do you think it’s a good solution for the audience’s needs? It’s often a good idea to start by defining the audience’s needs. Then you can fit the recommendation to the need. Keep it simple and use stories. Nobody remembers abstract logic and difficult technical concepts. They do remember stories.

Think about pathos both before the speech and in the conclusion. Ideally, you can meet the audience before your speech, ask insightful questions, and make personal connections. The more you can talk to members of the audience before the speech, the better off you’ll be. Look for anecdotes that you can use in your speech — that also builds your credibility. If nothing else, spend the last few minutes before your speech shaking hands with audience members and thanking them for coming to your speech. At the end of your speech, you can return to similar themes and express your appreciation. It’s also appropriate (usually) to point out how your recommendation will affect members of the audience personally. For instance, “We believe that our solution will help your company be more efficient. It will also help you build your career.”

Those of you who have followed my website for a while may remember my videos on ethos, logos, and pathos. I made them when I worked at Lawson Software and was teaching communication skills internally. Again, I’d like to thank Lawson for allowing me to use these videos on this website as I build my own practice.

By the way, all these suggestions apply to deliberative speeches. You present a logical argument and ask your audience to deliberate on it. On the other hand, you can also give a demonstrative speech where you throw the logic out altogether. They’re often called barn burners or stem winders. You can learn more here.