Branding and Archetypes

As you develop your company’s brand, how do you determine what “personality” you should project? How do you know where your brand fits relative to other brands in the market? I always recommend that you do as much market research as you can. I also recommend that you study the archetypal systems developed by Carol Pearson (whose website is here).

As you develop your company’s brand, how do you determine what “personality” you should project? How do you know where your brand fits relative to other brands in the market? I always recommend that you do as much market research as you can. I also recommend that you study the archetypal systems developed by Carol Pearson (whose website is here).

Pearson is a Jungian psychologist more than a marketing maven. She has developed a set of archetypes that help people understand how to use their inner resources to enrich their lives. Fortunately for us marketing types, these archetypes can also be applied to companies and organizations. They can help you understand how you fit into a broader ecosystem and how to convey your message most effectively.

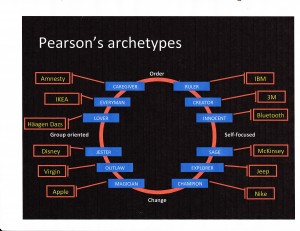

When I worked at Lawson Software, we used the simplified diagram that you see here. The diagram includes 12 basic archetypes with a company to illustrate each one.

The circle helps you understand how the archetypes fit together. For instance, note the word “Order” at the top of the circle and the word “Change” at the bottom. Simply put, the companies on the top half of the circle want to maintain the existing order, the current market structure. By comparison, the companies on the bottom half might be described as “upstarts”. They want to change — or overthrow — the current market structure.

The left and right halves of the circle also have much to tell us. The archetypes on the left side are group-oriented. Those on the right side are more self-focused. The simplest explanation is that those companies on the left of the circle focus primarily on their external constituencies. Those on the right focus more attention on internal processes and procedures.

At Lawson, we quickly decided that we were on the bottom half of the circle. We weren’t the market leaders, we didn’t dominate the segment — we needed to shake things up to find our place in the sun. Similarly, we decided that we were on the left side of the circle. We were market oriented and our mission was to make our customers stronger. In other words, we were externally focused.

So, we were on the lower left segment of the circle. We had three archetypes to choose from: 1) Jester, like Disney; 2) Outlaw, like Virgin; 3) Magician, like Apple. We then proceeded by elimination. We were a B2B company and just didn’t have the magical chops of Apple. Similarly, we weren’t a jester like Disney. Indeed, we were probably too serious.

That left us at “Outlaw”. We never really liked that label but ultimately we decided that’s who we were. (We described ourselves as “disrupters” rather than as “outlaws” but, really, what’s the difference?) To succeed, we needed to break some rules. We needed to be different and shake things up. It helped that we had a plain-spoken and charismatic CEO who was not unlike Richard Branson.

Choosing the outlaw/disrupter path almost immediately led us to use a cartoon character — very different than what you would expect from, say Oracle or SAP. With help from Fiftyeight, a very creative agency in Germany, we developed the Lars Lawson character as well as Sepp (for SAP) and ElCaro (Oracle spelled backwards). We then launched a series of video adventures on YouTube that typically garnered over a million views. (You can see the most popular videos here and here).

Did it work? You betcha. We grew faster than our segment and gained visibility globally. Bottom line: whether you’re a person or a company, it helps to know who you are and where you fit.

You can find Carol Pearson’s books here.

Brand Names: Offense

My clients often ask me to help them name things. They’re hoping that we can develop a name that plays equally well to logic and emotion and that states a compelling benefit in 15 letters or less. A lot of brains have been damaged this way.

My clients often ask me to help them name things. They’re hoping that we can develop a name that plays equally well to logic and emotion and that states a compelling benefit in 15 letters or less. A lot of brains have been damaged this way.

Great brand names often trigger emotional responses. But we often get the cause and effect backward. The name doesn’t put the emotion in us. We put the emotion in the name.

I worked in college and scraped together enough money to buy a beat-up Pontiac Tempest. The original Pontiac was a great Indian leader in the midwestern United States. The town of Pontiac, Michigan was named after him. General Motors opened a factory there and named the car after the town. Originally, the name Pontiac didn’t mean anything more to me than, say, the name Cotopaxi. It’s just a name. Then I bought the car and enjoyed driving it. Now Pontiac has a special meaning to me, some sentimental value. The name didn’t do anything to me. I did something to the name. That’s why naming is so difficult. The name doesn’t trigger anything until customers add emotion to it.

As Kevin Lane Keller and many other branding experts have pointed out, you can play offense or defense with a name — but it’s hard to do both. Consider three variables for offense:

- Memorability — anything you can do to make your name memorable will help build your brand. This may mean playing off a well-known word — as in Lincoln cars or Winston cigarettes. Be sure to link to something that has positive connotations. Repetition also builds memorability which is why marketers repeat themselves so often.

- Meaningfulness — a good name may identify a product category, or some key product features, or a major product benefit. Be aware that changes in perception may require you to change your name. When fried food came to be viewed as unhealthful, Kentucky Fried Chicken decided to change its name to KFC.

- Likability — it’s hard to know what makes a name likable. You may pick a popular person’s name. Animals often provide better names than people do. It’s hard to hate an animal whereas it’s not so hard to dislike some people. The more abstract a product or service is, the more important it is to focus on a likable name.

Building Brands by Building Trust

What’s a brand? In essence, it’s a promise that’s been consistently fulfilled. The promise has been kept in the past and we’ve come to trust that it will be fulfilled in the future. Coca Cola, for instance, has always tasted the same — no matter where or when the product is purchased. We’re confident that the same taste will be delivered in the future. In other words, we trust Coca Cola will keep its promise and we feel safe in buying the product. The brand has reduced risk and uncertainty in our lives.

What’s the essence of brand building? Consistently fulfilling the same promise. If the company behind the brand has many employees who deliver customer services, then they all must understand the brand promise and fulfill it in their daily activities. If they do, trust will be enhanced and the brand will grow. If they don’t, the lack of consistency undermines trust and customers lose confidence in the business. Customers will start to wonder whether they can trust that the brand will fulfill its promises in the future.

Learn more in the video.

Why is Warren Buffet’s Hair Messed Up?

Every time I see Warren Buffet on TV, his hair looks like it hasn’t seen a comb in years. Surely he can afford a comb. So, why is his hair so messy? I’m guessing that it’s a subtle — but persuasive — effort to brand himself as a smart guy. Who do we think of when we think of smart guys? Albert Einstein. What did his hair look like? It was a mess. I think we’re supposed to conclude that Albert and Warren are so busy thinking deep thoughts that they don’t have time to think about their appearance. It’s a good branding strategy. So what’s your personal branding strategy? Find out more in the video.

Every time I see Warren Buffet on TV, his hair looks like it hasn’t seen a comb in years. Surely he can afford a comb. So, why is his hair so messy? I’m guessing that it’s a subtle — but persuasive — effort to brand himself as a smart guy. Who do we think of when we think of smart guys? Albert Einstein. What did his hair look like? It was a mess. I think we’re supposed to conclude that Albert and Warren are so busy thinking deep thoughts that they don’t have time to think about their appearance. It’s a good branding strategy. So what’s your personal branding strategy? Find out more in the video.