Knowledge Neglect — Scots In Saris

If I ask you about the crime rate in your neighborhood, you probably won’t have a clear and precise answer. Instead, you’ll make a guess. What’s the guess based on? Mainly on your memory:

- If you can easily remember a violent crime, you’ll guess that the crime rate is high.

- If you can’t easily remember such a crime, you’ll guess a much lower rate.

Our estimates, then, are not based on reality but on memory, which of course is often faulty. This is the availability bias. Our probability estimates are biased toward what is readily available to memory.

The broader concept is processing fluency– the ease with which information is processed. In general, people are more likely to judge a statement to be true if it’s easy to process. This is the illusory truth effect– we judge truth based on ease-of-processing rather than objective reality.

It follows that we can manipulate judgment by manipulating processing fluency. Highly fluent information (low cognitive cost) is more likely to be judged true.

We can manipulate processing fluency simply by changing fonts. Information presented in easy-to-read fonts is more likely to be judged true than is information presented in more challenging fonts. (We might surmise that the new Sans Forgetica font has an important effect on processing fluency).

We can also manipulate processing fluency by repeating information. If we’ve seen or heard the information before, it’s easier to process and more likely to be judged true. This is especially the case when we have no prior knowledge about the information.

But what if we do have prior knowledge? Will we search our memory banks to find it? Or will we evaluate truthfulness based on processing fluency? Does knowledge trump fluency or does fluency trump knowledge?

Knowledge-trumps-fluency is known as the Knowledge-Conditional Model. The opposite is the Fluency-Conditional Model. Until recently, many researchers assumed that people would default to the Knowledge-Conditional Model. If we knew something about the information presented, we would retrieve that knowledge and use it to judge the information’s truthfulness. We wouldn’t judge truthfulness based on fluency unless we had no prior knowledge about the information.

A 2015 study by Lisa Fazio et. al. starts to flip this assumption on its head. The article’s title summarizes the finding: “Knowledge Does Not Protect Against Illusory Truth”. The authors write that, “An abundance of empirical work demonstrates that fluency affects judgments of new information, but how does fluency influence the evaluation of information already stored in memory?”

The findings – based on two experiments with 40 students from Duke University – suggest that fluency trumps knowledge. Quoting from the study:

“Reading a statement like ‘A sari is the name of the short pleated skirt worn by Scots’ increased participants later belief that it was true, even if they could correctly answer the question, ‘What is the name of the short pleated skirt worn by Scots?’” (Emphasis added).

The researchers found similar examples of knowledge neglect– “the failure to appropriately apply stored knowledge” — throughout the study. In other words, just because we know something doesn’t mean that we use our knowledge effectively.

Note that knowledge neglect is similar to the many other cognitive biases that influence our judgment. It’s easy (“cognitively inexpensive”) and often leads us to the correct answer. Just like other biases, however, it can also lead us astray. When it does, we are predictably irrational.

Ideas and Free Throws

Assume, for a moment, that I’m your manager. I call you into my office one day and say, “You’re doing pretty good work … but you’re going to have to get better at shooting free throws on the basketball court. If you want a promotion this year, you’ll need to make at least 75% of your free throws.”

What would you do? Assuming that you don’t resign on the spot, you would probably get a basketball, go to the free throw line, and start practicing free throws (also known as foul shots). Like most skills, you would probably find that your accuracy improves with practice. You might also hire a coach or watch some training videos, but the bottom line is practice, practice, practice.

Now, let’s change the scenario. I call you into my office and say, “You’re doing pretty good work … but you’re going to have to get better at creating ideas. If you want a promotion this year, you’ll need to increased the number of good ideas you generate by at least 75%.”

Now what? Well … I’d suggest that you start practicing the art of creating good ideas. In fact, I’d suggest that it’s not very different from practicing the art of shooting free throws.

But shooting free throws and creating ideas seem to be very different processes. Here’s how they feel:

- Shooting free throws – you get a basketball, you walk to the line – 15 feet from the basket – and you launch the ball into the air. You’re conscious of every action. You recognize that you’re the cause and a flying basketball is the result.

- Creating ideas – nothing happens … then, while you’re walking down the street, minding your own business – poof! – a good idea pops into mind. You have no sense of agency. Instead of feeling like the cause, you feel like the effect.

The two activities seem very different but, actually, they’re not. In both cases, you’re doing the work. With free throws, you readily recognize what you’re doing. With ideas, you don’t. Free throws happen in your conscious mind, also known as System 2. New ideas, on the other hand, happen below the level of consciousness, in System 1. When System 1 works up an idea, it pops it into System 2 and you become aware of it.

We understand how to practice something in System 2 – we’re aware of our activity. But how do we practice in System 1? How can we practice something that we’re not aware of?

We think of our mind as controlling our body. But, as Amy Cuddy has pointed out, our bodily activities also influence our mental states. If we make ourselves big, we grow more confident. If we smile, our mood brightens.

So how do we use our bodies to teach our brains to have good ideas? First, we need to observe ourselves. What were you doing the last time you had a good idea? I’ve noticed that most of my good ideas pop into my head when I’m out for a walk. When I’m stuck on a difficult problem, I recognize that I need a good idea. I quit what I’m doing and go for a walk. Oftentimes, it works – my System 1 generates an idea and pops it into System 2.

In my critical thinking classes, I ask my students to raise their hands if they have ever in their lives had a good idea. All hands go up. Everybody has the ability to create good ideas. The question is practice.

Then I ask my students what they were doing the last time they had a good idea. The list includes: out for a walk, driving, riding in a car, bus, or train (but not an airplane), taking a shower, drifting off to sleep, and bicycling.

I also ask them what activities don’t generate good ideas. The list includes: when they’re stressed, highly focused, multitasking, overly tired, overly busy, or sitting in meetings.

So how do we practice the art of having good ideas? By doing more of those activities that generate good ideas (and fewer of those that don’t). The most productive activities – like walking – seem to occupy part of our attention while leaving much of our brainpower free to wander somewhat aimlessly. Our bodily activity influences and stimulates our System 1. The result is often a good idea.

Is that perfectly clear? Good. I’m going for a walk.

One-Day Seminars – Fall 2018

This fall, in addition to my regular academic courses, I’ll teach three one-day seminars designed for managers and executives.

These seminars draw on my academic courses and are repackaged for professionals who want to think more clearly and persuade more effectively. They also provide continuing education credits under the auspices of the University of Denver’s Center for Professional Development.

If you’re guiding your organization into an uncertain future, you’ll find them helpful. Here are the dates and titles along with links to the registration pages.

- Saturday, September 29: Critical Thinking: How To Make Better Decisions (and Avoid Stupid Mistakes)

- Saturday, October 20: Innovation: How To Create Ideas That Generate Positive Results

- Saturday, November 10: Persuasion: How To Gain Agreement and Create Successful Teams

I hope to see you in one or more of these seminars. If you’re not in the Denver area, I can also take these on the road. Just let me know of your interest.

FOMO/JOMO. Be Here Now.

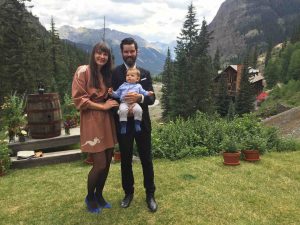

Julia and Elliot recently went to a wedding in Eureka, Colorado, a ghost town situated high in the San Juan Mountains. To say that Eureka is isolated is a vast understatement. Here are some things that the town doesn’t have: landlines, television, internet, wi-fi, mobile phone access, cable, newspapers, radio, and paved roads. When you’re there, you’re there.

Just before the wedding ceremony, ushers collected everyone’s cameras and mobile phones. The couple seemed to be saying to their guests: “We’re glad you’re here. We hope you’re with us fully and completely. Don’t fuss with your cameras and phones. Engage with us in a profound experience. Be here now.”

The place and the process reminded me of Daniel Kahneman’s definitions of the experiencing self and the remembering self. We can focus, engage our senses, and fully experience an activity. What we remember, however, is far different from what we experience. We typically remember two things: 1) the peak experience – the high point of the activity; 2) the end state – how things ended up. (For more on memory traps, click here).

The difference between the two selves has many implications. We remember things differently than they actually happened. This calls into question such things as eyewitness testimony and historical accounts. It may also be why we argue with our spouses – we simply remember things differently. It’s another good reason not to argue in the past tense. (For other reasons, click here).

The difference also affects how we plan our activities. We can plan to: 1) enhance the experience; or 2) enhance our memory of the experience. Let’s say you go to your favorite restaurant. If you want to enhance the experience, you should order your favorite dish. You can enjoy the anticipation and the experience itself. However, you won’t create a new memory. It will simply blend in with all the other times you’ve ordered the same dish. If you want a new memory, order something you’ve never had before. It may be great or not – you can’t anticipate – but it will be more memorable.*

FOMO, of course, is the Fear of Missing Out, which seems to be an increasing concern in today’s society. Everything is accessible and we don’t want to miss any of it. Technologies such a mobile phones, video chat, and instant messages democratize our experience. We can share anything with anyone at any time. We won’t miss a thing.

But, of course, we do miss things. In fact, the very act of inserting technologies into our experiences makes us miss some of the experience. We’re fussing with our cameras rather than experiencing the action. We’re checking baseball scores rather than engaging with others. The desire to miss nothing causes us to miss something: the intensity of the present moment.

FOMO shifts our attention from the experiencing self to the remembering self. We take pictures, which helps us remember and share an experience. But the act of taking pictures insulates us from the experience itself. We’ve inserted technology between our experiences and ourselves.

As you can probably guess, I’m not the first person to suggest that FOMO mania actually causes us to miss much more than we realize. The tech and culture blogger, Anil Dash, coined the term JOMO — the Joy Of Missing Out – more than two years ago. Christina Crook wrote a book called The Joy of Missing Out and popularized the idea of Internet fasts. Sarah Wilson points out that FOMO has eradicated traditional boundaries that separated public time from private time. It used to be easy to spend a quiet evening at home. Now we need to declare an Internet fast to get some alone time.

Though it’s not a new idea, I suspect that the JOMO message needs some more evangelists. As a famous American once said: Be Here Now.

*I adopted the restaurant example from an episode of the Hidden Brain podcast called Hungry, Hungry Hippocampus.

Information Avoidance and Persuasion

The 1989 Tour de France was decided in the last stage, a 15.2 mile time trial into Paris. The leader, Laurent Fignon, held a fifty second advantage over Greg LeMond. Both riders were strong time trialers. To make up fifty seconds in such a short race seemed impossible. Most observers assumed that Fignon would hold his lead and win the overall title.

In most time trials, coaches radio the riders to inform them of their speed, splits, and competitive position. In this final time trial, however, LeMond turned off his radio. He didn’t want to know. He feared that, if he knew too much, he might ease up. Instead, he raced flat out for the entire distance, averaging 33.9 miles per hour, a record at the time. In a stunning finish, LeMond gained 58 seconds on Fignon and won the race by a scant eight seconds. (Here’s a terrific video recap of the final stage).

LeMond’s strategy is today known as information avoidance. He chose not to accept information that he knew was freely available to him. LeMond knew that he might be distracted by the information. He chose instead to focus solely on his own performance – the only variable that he could control.

While information avoidance worked for LeMond, the strategy often yields suboptimal outcomes. We choose not to know something and the not knowing creates health hazards, financial obstacles, and a series of unfortunate events. Here are some examples.

- In a study of 7,000 employees at a large non-profit organization, Giulio Zanella and Ritesh Banerjee found that women are less likely to get a mammogram when one of their co-workers is diagnosed with breast cancer. The mammogram rate dropped by approximately eight percent and the effect lasted for at least two years. (Click here).

- Amanda Ganguly and Josh Tasoff offered students tests to determine if they carried the herpes simplex virus. Though the tests were free and readily available, about five percent of the students refused the test for the HSV1 form of the virus. Fifteen percent refused the test for the HSV2 form of the virus, which is widely regarded as the “nastier” version. In other words, the scarier the disease, the more likely people are to avoid information about it. (Click here).

- Marianne Andries and Valentin Haddad investigated similar effects in financial decisions. They found that “…information averse investors observe the value of their portfolios infrequently; inattention is more pronounced …in periods of low or volatile stock prices.” Again, the scarier the situation, the less likely people are to search for information about it. (Click here).

- Russell Golman, David Hagmann, and George Loewenstein also investigated economic decision making and identified five information avoidance techniques: 1) physical avoidance; 2) inattention; 3) biased interpretation; 4) forgetting; 5) self-handicapping. (Click here).

In some ways, information avoidance is the flip side of the confirmation bias. We accept information that confirms our beliefs and avoid information that doesn’t. But there seems to be more to avoidance than simply the desire to avoid disconfirming information. Other contributors include:

- Focus and fatalism – why learn something that we can do nothing about? I suspect that this was LeMond’s motivation. He couldn’t do anything about the information, so why receive it? Instead he focused on what he could do.

- Anxiety – why learn something that will simply make us anxious? The scarier it is, the more anxious we’ll be. We’ve all put off visits to the doctor because we just don’t want to know.

- Ego threat – why learn something that will shake our confidence in our own abilities? It seems, for instance, that poor teachers are less likely to pay attention to student evaluations than are good teachers.

Information avoidance can also teach us about persuasion. If we want to persuade people to change their opinion about something, making it scarier is probably self-defeating. People will be more likely to avoid the information rather than seeking it out. Similarly, bombarding people with more and more information is likely to be counter-productive. People under bombardment become defensive rather than open-minded.

As Aristotle noted, persuasion consists of three facets: 1) ethos (credibility); 2) pathos (emotional connection); 3) logos (logic and information). Today, we often seek to persuade with logos – information and logic. But Aristotle taught that logos is the least persuasive facet. We typically use logos to justify a decision rather than to make a decision. Ethos and pathos are much more influential in making the decision. The recent research on information avoidance suggests that we’ll persuade more people with ethos and pathos than we ever will with logos. Aristotle was right.

Greg LeMond’s example shows that information avoidance can provide important benefits. But, as we develop our communication strategies, let’s keep the downsides in mind. We need to package our arguments in ways that will reduce information avoidance and lead to a healthier exchange of ideas.