Somatopsychic Chewing Gum

No flu here!

Psychosomatic illness is one that is “caused or aggravated by a mental factor such as internal conflict or stress”. We know that the brain can create disturbances in the body. But what about the other way round? Can we have somatopsychic illnesses? Or could the body produce somatopsychic wellness – not a disease but the opposite of it?

I’ve written about embodied cognition in the past (here, here, and here). Our body clearly influences the way we think. But could our body influence the way we think and our thinking, in turn, influence our body? Here are some interesting phenomena I’ve discovered recently in the literature.

Exercise and mental health – I’ve seen a spate of articles on the positive effects of physical exercise on mental health. This truly is a somatopsychic effect. Among other things, raising your heartbeat increases blood flow to your brain and that’s a very good thing. Exercise also reduces stress, elevates your mood, improves your sleep, and – maybe, just maybe – improves your sex life.

Chewing gum and annoying songs – ever get an annoying song in your head that just won’t go away? For me, it’s the theme from Gilligan’s Island. New research suggests that chewing gum could alleviate – though not completely eliminate – the song. One researcher noted that, “producing movements of the mouth and jaw [can] affect memory and the ability to imagine music.” Why jaw movements would affect memory is anyone’s guess.

Hugs and colds – could hugging other people help you reduce your chances of catching a cold? You might think that hugging other people – especially random strangers – would increase your exposure to cold germs and, therefore, to colds. But it seems that the opposite is, in fact, the case. The more you hug, the less likely you are to get a cold. Hugging is a good proxy for your social support network. People with strong social support are less likely to get sick (or to die, for that matter). Even if you don’t have strong social support, however, increasing your daily quota of hugs seems to have a similar effect.

Sitting or standing? – do you think better when you’re sitting down or standing up? At least for young children – ages seven to 10 – standing up seems to produce much better results. Side benefit: standing at a desk can burn 15% to 25% more calories than sitting. Maybe this is why it’s a good thing to be called a stand-up guy.

Clean desk or messy desk (and here) – it depends on what behavior you’re looking for. People with clean desks are more likely “to do what’s expected of them.” They tend to conform to rules more closely and behave in more altruistic ways. People at messy desks, on the other hand, were more creative. The researchers conclude: “Orderly environments promote convention and healthy choices, which could improve life by helping people follow social norms and boosting well-being. Disorderly environments stimulated creativity, which has widespread importance for culture, business, and the arts.”

So, what does it all mean? As we’ve learned before, the body and the brain are one system. What one does affects the other. Behavior and thinking are inextricably intertwined. When your brain wanders, don’t let your feet loaf.

McKinsey and The Decision Villains

Just roll the dice.

In their book, Decisive, the Heath brothers write that there are four major villains of decision making.

Narrow framing – we miss alternatives and options because we frame the possibilities narrowly. We don’t see the big picture.

Confirmation bias – we collect and attend to self-serving information that reinforces what we already believe. Conversely, we tend to ignore (or never see) information that contradicts our preconceived notions.

Short-term emotion – we get wrapped up in the dynamics of the moment and make premature commitments.

Overconfidence – we think we have more control over the future than we really do.

A recent article in the McKinsey Quarterly notes that many “bad choices” in business result not just from bad luck but also from “cognitive and behavioral biases”. The authors argue that executives fall prey to their own biases and may not recognize when “debiasing” techniques need to be applied. In other words, executives (just like the rest of us) make faulty assumptions without realizing it.

Though the McKinsey researchers don’t reference the Heath brothers’ book, they focus on two of the four villains: the confirmation bias and overconfidence. They estimate that these two villains are involved in roughly 75 percent of corporate decisions.

The authors quickly summarize a few of the debiasing techniques – premortems, devil’s advocates, scenario planning, war games etc. – and suggest that these are quite appropriate for the big decisions of the corporate world. But what about everyday, bread-and-butter decisions? For these, the authors suggest a quick checklist approach is more appropriate.

The authors provide two checklists, one for each bias. The checklist for confirmation bias asks questions like (slightly modified here):

Have the decision-makers assembled a diverse team?

Have they discussed their proposal with someone who would certainly disagree with it?

Have they considered at least one plausible alternative?

The checklist for overconfidence includes questions like these:

What are the decision’s two most important side effects that might negatively affect its outcome? (This question is asked at three levels of abstraction: 1) inside the company; 2) inside the company’s industry; 3) in the macro-environment).

Answering these questions leads to a matrix that suggests the appropriate course of action. There are four possible outcomes:

Decide – “the process that led to [the] decision appears to have included safeguards against both confirmation bias and overconfidence.”

Reach out – the process has been tested for downside risk but may still be based on overly narrow assumptions. To use the Heath brothers’ terminology, the decision makers should widen their options with techniques like the vanishing option test.

Stress test – the decision process probably overcomes the confirmation bias but may depend on overconfident assumptions. Decision makers need to challenge these assumptions using techniques like premortems and devil’s advocates.

Reconsider – the decision process is open to both the conformation bias and overconfidence. Time to re-boot the process.

The McKinsey article covers much of the same territory covered by the Heath brothers. Still, it provides a handy checklist for recognizing biases and assumptions that often go unnoticed. It helps us bring subconscious biases to conscious attention. In Daniel Kahneman’s terminology, it moves the decision from System 1 to System 2. Now let’s ask the McKinsey researchers to do the same for the two remaining villains: narrow framing and short-term emotion.

Three Decision Philosophies

I’ll use the rational, logical approach for this one.

In my critical thinking classes, students get a good dose of heuristics and biases and how they affect the quality of our decisions. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky popularized the notion that we should look at how people actually make decisions as opposed to how they should make decisions if they were perfectly rational.

Most of our decision-making heuristics (or rules of thumb) work most of the time but when they go wrong, they do so in predictable and consistent ways. For instance, we’re not naturally good at judging risk. We tend to overestimate the risk of vividly scary events and underestimate the risk of humdrum, everyday problems. If we’re aware of these biases, we can account for them in our thinking and, perhaps, correct them.

Finding that our economic decisions are often irrational rather than rational has created a whole new field, generally known as behavioral economics. The field ties together concepts as diverse as the availability bias, the endowment effect, the confirmation bias, overconfidence, and hedonic adaptation to explain how people actually make decisions. Though it’s called economics, the basis is psychology.

So does this mean that traditional, rational, statistical, academic decision-making is dead? Well, not so fast. According Justin Fox’s article in a recent issue of Harvard Business Review, there are at least three philosophies of decision-making and each has its place.

Fox acknowledges that, “The Kahneman-Tversky heuristics-and-biases approach has the upper hand right now, both in academia and in the public mind.” But that doesn’t mean that it’s the only game in town.

The traditional, rational, tree-structured logic of formal decision analysis hasn’t gone away. Created by Ronald Howard, Howard Raiffa, and Ward Edwards, Fox argues that the classic approach is best suited to making “Big decisions with long investment horizons and reliable data [as in] oil, gas, and pharma.” Fox notes that Chevron is a major practitioner of the art and that Nate Silver, famous for accurately predicting the elections of 2012, was using a Bayesian variant of the basic approach.

And what about non-rational heuristics that actually do work well? Let’s say, for instance, that you want to rationally allocate your retirement savings across N different investment options. Investing evenly in each of the N funds is typically just as good as any other approach. Know as the 1/N approach, it’s a simple heuristic that leads to good results. Similarly, in choosing between two options, selecting the one you’re more familiar with usually creates results that are no worse than any other approach – and does so more quickly and at much lower cost.

Fox calls this the “effective heuristics” approach or, more simply, the gut-feel approach. Fox suggests that this is most effective, “In predictable situations with opportunities for learning, [such as] firefighting, flying, and sports.” When you have plenty of practice in a predictable situation, your intuition can serve you well. In fact, I’d suggest that the famous (or infamous) interception at the goal line in this year’s Super Bowl resulted from exactly this kind of thinking.

And where does the heuristics-and-biases model fit best? According to Fox, it helps us to “Design better institutions, warn ourselves away from dumb mistakes, and better understand the priorities of others.”

So, we have three philosophies of decision-making and each has its place in the sun. I like the heuristics-and-biases approach because I like to understand how people actually behave. Having read Fox, though, I’ll be sure to add more on the other two philosophies in upcoming classes.

Maps, Isms, and Assumptions

Looks good to me.

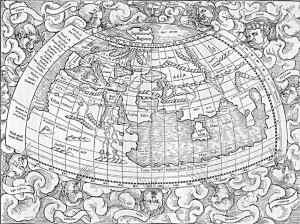

I have a map printed in Germany around 1530 that shows the world as it was seen by second century Greeks. Why would Europeans print a map that was based on sources roughly 15 centuries old? Because Europeans assumed the Greeks knew what they were doing.

Claudius Ptolemy, a Greek mathematician living in Alexandria, wrote a textbook called Geography in 150 AD. The book was so popular and reprinted so frequently – often in Arabic – that Ptolemy became known as the Father of Geography.

My map bears the heading, Le Monde Selons Ptol. or The World According to Ptolemy. It doesn’t include America even though it was printed roughly 40 years after Columbus sailed and roughly 25 years after the Waldeseemüller map became the first map ever to use the word “America”.

When my map was printed, Europe was going through an intellectual revolution. The basic question was: should we believe our traditional sources or should we believe our eyes? Should we copy Greek and Arabic sources or should we observe the world around us? Should we simply accept the Greek version of the world (as we have for so many centuries) or is “progress” something we can realistically aim for?

For centuries, Europeans assumed that the Greeks knew it all. There was no point observing the world and learning new tricks. One could live the best life by bowing to tradition, authority, and faith. This assumption held, in many quarters, until the early 16th century. Then it rapidly changed. You can see it in the maps. By 1570, most maps were in the style of tavola nuova — new maps — based on actual observations. The world had changed and, indeed, the tavolas nuovas look quite a bit like the maps we’re familiar with.

Let’s fast forward to 1900. What did we assume then? Three isms dominated our thinking: Darwinism, Marxism, and Freudianism. Further, we assumed that physics was almost finished – we had only a few final problems to work out and then physics would be complete. We assumed that we were putting the finishing touches on our knowledge of ourselves and the world around us.

But, of course, we weren’t. Today, Darwinism survives (with some enhancements) but Marxism and Freudianism have been largely cast aside. And physics is nowhere near complete. In fact, it seems that the more we learn, the more confused we become.

Even in my lifetime, our assumptions have changed dramatically. We used to believe that economics was rational. Now we understand how irrational our economic decisions are. We once assumed that the bacteria in our guts were just along for the ride. Now we believe they may fundamentally affect our behavior. We used to believe that stress caused ulcers. Now we know it’s a bacteria. Indeed, we seem to have gotten many things backwards.

And what are we assuming to be true today that will be proved wrong tomorrow? In the 16th century, we believed in eternal truths handed down for centuries. I suspect the 21st century won’t be a propitious time for eternal truths. The more we learn, the weirder it will get. Hang on to your hat. That may be all you’ll be able to hang onto.

Improving Self-Control

Use your left hand.

Yesterday I wrote about self-esteem and self-control. In the last thirty years of the 20th century, we thought that self-esteem might be the key to success. Now we think of self-esteem as the result of success rather than the cause of it. What counts is self-control or, as some writers phrase it, the building of character.

So how do we improve self-control? The short answer is that we need to practice it just as we practice any other skill. Here are eight suggestions from the research literature.

Use your non-dominant hand more frequently – researchers asked people to use their non-dominant hand for routine activities, like drinking coffee, for two weeks. Because these tasks restrained “natural inclinations” they required constant self-control. At the end of two weeks, the participants had better self-control and also “controlled their aggression better than others” who had not participated. You may well get similar results by improving your posture or policing your language.

Think about God – Kevin Rounding and his colleagues conducted experiments in which participants completed a variety of self-control exercises. Prior to the exercises, half the group played word puzzles that contained religious or divine themes. The other half played similar word puzzles with non-religious themes. Those who were exposed to religious themes had better self-control.

Laughter – laughter apparently interrupts your thought processes in useful ways. Rather than focusing on self-regulation, you can gain a brief reprieve. You let your “willpower muscle” relax and replenish.

Don’t use social media – consumer researchers, Keith Wilcox and Andrew Stephen, studied the effects of browsing social media on post-browsing behavior. They found that browsing social media increases self-esteem, which has negative behavioral effects. “This momentary increase in self-esteem reduces self-control, leading those [who browse] to display less self-control after browsing a social network compared to not browsing a social network.”

Focus on long-term goals – researchers Nidhi Agrawal and Echo Wen Wan found that health-related communications have more impact on ego-depleted people when the message focuses on long-term goals. “[W]hen [the participants] looked to the future and linked the health task to important long-term goals, they exerted self- control and were not affected by being tired or depleted. “

Clench your muscles – perhaps your physical muscles and your willpower muscles are related. Consumer researchers Iris Hung and Laparna Labroo found that embodied cognition plays a role in self-control. Participants who clenched a muscle – a fist, the calves, whatever – showed better self-control than those who didn’t.

Don’t banish the treat – researchers at Catholic University in Leuven, Belgium found that the presence of an actual treat – like M&Ms – improved participants’ self-control. The treats are actionable – you can grab a handful and eat them or decide not to. Deciding not to is an action that improves self-control in ways that avoidance doesn’t. Actionability proved to be a “pivotal variable” in self-control strategies.

Say “I don’t” rather than “I can’t” – perhaps the importance of actionability comes from emphasis on choice. A study by Vanessa Patrick, a marketing professor at the University of Houston, examined the wording of self-talk on self-control. “When participants framed a refusal as ‘I don’t’ (for instance, ‘I don’t eat sugar’) instead of ‘I can’t,’ they were more successful at resisting the desire to eat unhealthy foods or skip the gym.” Patrick comments, ““Saying ‘I can’t’ connotes deprivation, while saying ‘I don’t’ makes us feel empowered and better able to resist temptation.”

There’s plenty more research on self-control that I expect to write about in the near future. Interestingly, some of the best articles come from consumer researchers and marketers. They apparently want to understand how our self-control works so they can manipulate it. Stay tuned.