Good News on Dementia?

Harriet speaks to the future.

My mother-in-law, Harriet, is a delightful nonagenarian who is still as sharp as a tack. What’s the secret to her mental acuity? I’m willing to bet that the fact that she’s an avid bridge player has something to do with it.

Indeed, Harriet may be a leading indicator of the changing shape of the dementia demographic. Conventional wisdom holds that our health care system is about to be overwhelmed as the baby boom ages and sinks into dementia.

The logic is straightforward. Major premise: Old age is the leading risk factor for dementia. Minor premise: People are living longer. Conclusion: Everybody will become demented sooner or later and our health care system will collapse.

In the current issue of New Scientist, however, Liam Drew reports on new research that suggests that Harriet may be an emblem of change, not an exception to it. As Drew points out, the conventional wisdom “… is based on the assumption that people will continue to develop dementia at the same rate as they always have.” Drew then reports on two studies that suggest this assumption is no longer true (if it ever was).

The first is a research report from the Lancet that compares two dementia censuses conducted 20 years apart in three regions the U.K. The first census, conducted in 1994, counted 650,000 people with dementia. In 2013, the researchers repeated the study and, assuming that the dementia rate held steady, projected that they would find 900,000 people with dementia. Instead, they found about 700,000. The report concludes that, “Later-born populations have a lower risk of prevalent dementia than those born earlier in the past century.”

The second study, conducted in Denmark, reached essentially the same conclusion. The research compared people born in 1905 with those born in 1915. Drew reports that, “While the two groups had similar physical health, those born in 1915 markedly outperformed the earlier-born in cognitive tests.”

So, what’s going on? Well, for one thing, we’re taking better care of our hearts. In general, healthier hearts provide better circulation. More oxygen-rich blood reaches our brains, which probably improves brain health. A heart healthy lifestyle may also be a brain healthy lifestyle.

Another theory is cognitive reserve, which suggests that we may be able to make our brains more resilient and resistant to damage. In other words, the brain is not just a “given”; it can be developed in much the same way that a muscle can. As Wikipedia puts it, “Exposure to an enriched environment, defined as a combination of more opportunities for physical activity, learning and social interaction, may produce structural and functional changes in the brain and influence the rate of neurogenesis … many of these changes can be affected merely by introducing a physical exercise regimen rather than requiring cognitive activity per se.”

What creates cognitive reserve? Educational attainment seems to play an important role. Physical and social activity also seem to contribute. I can’t help but wonder whether playing bridge – which combines social and cognitive elements – might not be the perfect way to build our cognitive reserves.

Over the years, we’ve all learned a lot from Harriet. She’s smart and she’s wise. And she may just have taught us how to live intellectually rich lives for many years to come. Thank you, Harriet.

Design As A Competitive Weapon

Design thinking

When we think of design, we often think of things. We can design a phone, a car, a coffee maker, or a house. We can make them simple or complex or modern or traditional but, ultimately, it’s a thing, a physical object.

Many business and organizational leaders are now arguing that we’re thinking too narrowly when we define design as for-things-only. Roger Martin, the former Dean of the Rotman School of Management, sums it up nicely, “…everything that surrounds us is subject to innovation – not just physical objects, but political systems, economic policy, the ways in which medical research is conducted, and complete user experiences.”

Two things, in particular, attract me to design thinking:

It starts with a solution – in design thinking, we first imagine what could be. Then we work backwards. What might a solution look like? What would it need to include? Who would need to be involved? Many business leaders start with the problem and focus on what went wrong. Design thinkers focus on the solution and what could go right. It’s a refreshing change.

It includes both the rational and irrational – I studied a lot of economics and I was always a bit uncomfortable with the starting assumption: we’re dealing with economically rational individuals. But are we really economically rational? The whole school of behavioral economics (which evolved after I graduated) says no. As Paola Antonelli points out, design thinking involves “the complete human condition, with all of its rational and irrational aspects….”

In past articles (here, here, and here), I’ve followed Paul Nutt’s lead and written about decision-making that leads to debacles. I’ve recently re-analyzed Nutt’s case studies of several dozen debacles and – as far as I can tell – none of them used design thinking. The debacles resulted from classic decision-making processes driven by successful business executives. Would those executives have done better with design thinking? It’s hard to say but they could hardly have done worse.

Is design thinking superior to classic business decision-making? The absence of design-driven debacles in Nutt’s sample is suggestive but not definitive. Are there positive examples of design-driven business success? Well, yes. In fact, close readers of this website may remember Roger Martin’s name. He was the “principal external strategy advisor” to A.G. Lafley, the highly lauded CEO of Procter & Gamble. According to a report from A.T. Kearney, “During Lafley’s tenure, sales doubled, profits quadrupled, and the company’s market value increased by more than $100 billion”.

Does one success – and the absence of debacles – prove that design thinking is superior to classic business thinking? No … but it sure is intriguing. So, I’m trying to unlearn years of system thinking and teach myself the basics of design thinking. As I do, I’ll write about design thinking frequently. I hope you’ll join me.

(By the way, the quotes from Roger Martin and Paola Antonelli are drawn from Rotman on Design: The Best Design Thinking From Rotman Magazine, which I highly recommend).

Groups Get It Wrong (All Too Often)

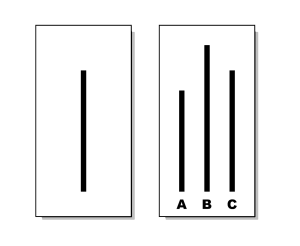

The right answer is obviously B.

Why do decisions go wrong? Many times, it’s because the decision is made by a group, not by an individual. Individuals tend to look at the evidence and make a decision. It may not be the right decision but it’s often based on an assessment of the facts.

Groups may assess the facts as well but they also assess the politics of the situation. The issue may be decided on group dynamics rather than a dispassionate review of the evidence.

Bain & Company recently published a white paper (Decision Insights: How Group Dynamics Affect Decisions) that provides a useful summary of the issues. Here are four ways, for instance, that group dynamics can lead to debacles.

Conformity – if you’re a team player, you may go with the team’s decision even if you realize it’s wrong. The graphic above shows Solomon Asch’s classic experiment. Which line – A, B, or C – is the same length as the line to the left? Working alone, you’ll probably figure out that C is the right answer. However, if you’re in a group that says B is the right answer, you’re quite likely to go with the group. Many companies say they want team players, but they need to be aware of the implications. (See also Group Behavior – The Risky Shift.)

Group Polarization – let’s assume for a moment that you belong to a politically conservative group. You talk to conservatives regularly. Indeed, you talk only to conservatives. You reinforce each other and the group gets more and more conservative. In many cases, the group becomes more conservative than any of its individual members. (See also, Will The Internet Cause Dementia? and Where You Stand Depends on Where You Sit.)

Obedience to Authority – the quickest way to stifle innovation is to let the boss speak first. We all want to please our bosses, so if the boss expresses a preference for X over Y, we often begin to find reasons why X is indeed better than Y. It’s hard to argue with your boss … unless you’re specifically asked to play the role of devil’s advocate, which is often a good idea. Note to bosses: keep quiet. (See also, Want A Good Decision? Go To Trial.)

Bystander Effect – when we’re not sure what to do, we often look to others to see what they’re doing. If they’re panicking, we get panicky. If they’re cool, calm, and collected, we calm down (even if we think we should panic). Individuals often understand a situation better than groups do which is why you should never have a heart attack in a crowd.

So, what to do? Diversity in a group often helps overcome groupthink and polarization, so pull people together from different backgrounds and risk profiles. Playing roles can help. You might stage a mock trial or ask someone to play the devil’s advocate. You can also ask each individual to write down his or her recommendation anonymously, put them all in a hat, and then discuss all of them. You can also prime the team by discussing what it means to be a team player. Emphasize the need to make the best decision, not just the most comfortable one.

And, if all else fails, just ask the boss to leave the room.

Seeing And Observing Sherlock

Pardon me while I unitask.

I’m reading a delightful book by Maria Konnikova, titled Mastermind: How To Think Like Sherlock Holmes. It covers much of the same territory as other books I’ve read on thinking, deducing, and questioning but it reads more like … well, like a detective novel. In other words, it’s fun.

In the past, I’ve covered Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast and Slow. Kahneman argues that we have two thinking systems. System 1 is fast and automatic and always on. We make millions of decisions each day but don’t think about the vast majority of them; System 1 handles them. System 1 is right most of the time but not always. It uses rules of thumb and makes common errors (which I’ve cataloged here, here, here, and here).

System 1 can also invoke System 2 – the system we think of when we think of thinking. System 2 is where we logically process data, make deductions, and reach conclusions. It’s very energy intensive. Thinking is tiring, which is why we often try to avoid it. Better to let System 1 handle it without much conscious thought.

Kahneman illustrates the differences between System 1 and System 2. Konnikova covers some of the same territory but with slightly different terminology. Konnikova renames System 1 as System Watson and System 2 as System Holmes. Konnikova proceeds to analyze System Holmes and reveal what makes it so effective.

Though I’m only a quarter of the way through the book, I’ve already gleaned a few interesting tidbits, such as these:

Motivation counts – motivated thinkers are more likely to invoke System Holmes. Less motivated thinkers are willing to let System Watson carry the day. Konnikova points out that thinking is hard work. (Kahneman makes the same point repeatedly). Motivation helps you tackle the work.

Unitasking trumps multitasking – Thinking is hard work. Thinking about multiple things simultaneously is extremely hard work. Indeed, it’s virtually impossible. Konnikova notes that Holmes is very good at one essential skill: sitting still. (Pascal once remarked that, “All of man’s problems stem from his inability to sit still in a room.” Holmes seems to have solved that problem).

Your brain attic needs a spring cleaning – we all have lots of stuff in our brain attics and – like the attics in our houses – a lot of it is not worth keeping. Holmes keeps only what he needs to do the job that motivates him.

Observing is different than seeing – Watson sees. Holmes observes. Exactly how he observes is a complex process that I’ll report on in future posts.

Don’t worry. I’m on the case.

Red Wine and Best-of-Breed Education

Nice chateau. Pity about the wine.

Some years ago I went with colleagues to a very traditional French restaurant in New Orleans. I asked for the wine list and received a very large book filled with French wines. I turned to the section on Bordeaux wines and found that it was organized by the Official Classification of 1855 as requested by Napoleon III. I thought, “Really? They want me to select a wine based on what people thought in 1855?”

The traditional way to evaluate French wines was to review the history of the chateau, identify the best winemakers, discuss the soil, humidity, and sunlight of the vineyard (the terroir), study the label, the bottle, and the cork, and then – and only then – taste the wine. Only by studying the wine’s history and pedigree could you truly appreciate what was in the glass. If you knew your history, the label would tell you what to expect.

Beginning in the 1970s, the wine world began to flip the model, largely because of the influence of California vintners. Rather than focusing on history (California had none) and traditional markers of prestige, the emphasis shifted to what’s in the glass. How does it taste? What can you discern by sniffing and sampling the wine? What flavors are in the glass? What flavors should be in the glass?

Blind taste tests began to replace traditional French methods of evaluating wines. In the Paris Wine Tasting of 1976 (often known as The Judgment of Paris), French judges were shocked when they learned that they themselves had rated many California wines better than elite French wines. Indeed, a California wine was judged the best white wine in the competition. (You can read about the competition – and a lot more – in Lawrence Osborne’s book, The Accidental Connoisseur).

So what does wine tasting have to do with higher education? Well, it strikes me that we’re still evaluating students using the traditional French method of evaluating wine. If the chateau that produced the wine has a good reputation, then the wine in the glass must be good. If the school the student attended has good reputation, then the student must be well educated.

It’s all rather silly, isn’t it? What we really want to know is how good is the wine and how well educated is the student. A prestigious chateau can produce a terrible wine. An elite university can produce poorly educated students.

Flipping the higher education model would create a student-centric model. Just as we ask, what’s in the glass?, so we should ask what’s in the student? It’s not about the reputation of the institution; it’s about how well the student has absorbed the education and what he or she can do with it.

Today, we’re accustomed to rating wines on a 100-point scale based on blind tastings. (I think the French are still annoyed by this). Why can’t we do the same with students? Is the educational bureaucracy the only obstacle? Then I think there’s hope. After all, we flipped the wine model in France … and they’re the ones who invented the word bureaucrat.