Better Decisions for Your Company – 2

Yesterday we looked at the first three steps in Decide & Deliver: 5 Steps to Improving Your Organization’s Decision-Making. (The book is here; the white paper is here). Let’s look at the last two steps today.

Yesterday we looked at the first three steps in Decide & Deliver: 5 Steps to Improving Your Organization’s Decision-Making. (The book is here; the white paper is here). Let’s look at the last two steps today.

Step 4 – Build an Organization. The first three steps outline the decision making process. If you do all three of them well, the decision quality will improve. But, in addition to making decisions, you need to create an organization that is tuned for decision making. This especially affects those small but frequent operational decisions.

The authors suggest that the starting point is fairly simple: judge investments based on their ability to improve decisions and execution. You may want to include other criteria as well – competitive positioning, return on capital, and so on. But always be sure to include a decision quality objective as well.

The authors illustrate their point with the war for talent. Here’s the difference:

- Traditional approach: Are we winning the war for talent?

- Decision-centered approach: Do we put our best people in the jobs where they can have the biggest impact on decisions?

Looking at your organization from this perspective will change your understanding of how your best people should be deployed. You may find that executive and managerial positions are less “decision-critical” than you thought and many operational positions are more important. You’ll probably want to deploy your best people in different ways.

Step 5 – Embed Decision Capabilities. This one is “about making change stick” and runs in parallel with the other steps. In other words, it’s not the last step in a chronological sequence. Rather, it’s a concurrent step. You build a foundation, engage your best leaders, identify the decision-critical positions, redeploy people, and set audacious goals.

There are obstacles, of course. You may find that important decisions makers (and decision centers) may lose authority as decisions are pushed down and out. Other people may not want to change. They’re comfortable with their current routines. They may not change at all or they may apply the new method of decision making only to the easy decisions. These are all predictable issues. Be prepared for them.

What happens if you successfully complete all five steps? Performance will probably improve on key metrics like customer satisfaction, revenues, and profits. More importantly, you may just set the organization into a virtuous circle (as opposed to a vicious circle). Good decisions produce better decisions which attracts better talent which produce better decisions which … well, you get the idea.

Better Decisions for Your Company – 1

Several years ago Marcia Blenko, Michael Mankins, and Paul Rogers (all Bain consultants) wrote a book called Decide & Deliver – 5 Steps to Breakthrough Performance in Your Organization. Recently, they converted it into a white paper. Since their research provides important clues for improving decision making, I’d like to summarize it today and tomorrow. I hope it will encourage you to read more – it’s useful stuff.

Several years ago Marcia Blenko, Michael Mankins, and Paul Rogers (all Bain consultants) wrote a book called Decide & Deliver – 5 Steps to Breakthrough Performance in Your Organization. Recently, they converted it into a white paper. Since their research provides important clues for improving decision making, I’d like to summarize it today and tomorrow. I hope it will encourage you to read more – it’s useful stuff.

Step 1 – Score Your Organization. Most of us don’t give our organizations a grade for the quality of our decisions. But we rate ourselves on most everything else, so why not decision making? The authors suggest a broad survey of managers and employees, followed by face-to-face interviews. Ask four basic questions:

- Quality — How often do you choose the right course of action?

- Speed — How quickly do you make decisions versus competitors?

- Yield – How often do you execute decisions as intended?

- Effort – Do you put the right amount of effort into making and executing decisions?

These are simple, straightforward questions but I suspect that most of our organizations don’t give much thought to them. Once you’ve gathered the information, Bain has a database of companies to benchmark against.

Step 2 – Focus on Key Decisions. You can’t evaluate every decision, so identify the critical ones in two different categories: 1) Big, high-value strategic choices – most of these are obvious. 2) Operating decisions that “are made and remade frequently and generate a lot of value over time.” These are less obvious but might include things like merchandising decisions. Companies often make millions of merchandising decisions; shifting even a small percentage from “bad” to “good” can make a huge difference.

To identify the most important decisions, consider two key attributes:

- Value at stake – don’t forget to multiply value by frequency. Doing so will help you identify high-value operating decisions.

- Degree of management attention required – can the decision be pushed down the hierarchy and out toward the customer or does it percolate upward? Decisions that require a lot of attention often provide “greater scope for improvement.”

The authors also suggest using the Decision X-Ray. When a decision goes bad, don’t just fix it. Study how the decision was made and identify the factors that caused it to fail. Then apply the lessons to future decisions.

Step 3 – Make Decisions Work. Four elements here: What, Who, How, and When.

- Clarify the What – don’t just focus on “whether-or-not” decisions – as in, “We need to decide whether or not to buy Company X”. Expand the decision, as in “What’s the best way to invest our capital?”

- Determine the Who – consider the acronym RAPID and identify people who need to Recommend, others who provide Input, others who need to buy into or Agree to the decision, someone(s) to make the final Decision, and others who Perform or execute the decision.

- Understand the How – how will you make the decision … by popular vote? By consensus? By a key executive?

- Make the When explicit – “A schedule ensures that decisions are quickly followed by action so that things can happen rapidly and the hurdle to reopen the decisions is high.”

Tomorrow: Steps 4 and 5: Build an Organization and Embed Decision Capabilities.

Braess’s Paradox and The Super Bowl

Of course they’ll win.

Braess’s paradox posits that adding capacity to a network can reduce the network’s performance. Conversely, removing links in the network can improve its performance.

Dietrich Braess, a German mathematician, originally identified the phenomenon in traffic flows. As new roads open up, overall traffic flows sometimes slow down. That’s certainly unexpected behavior.

The paradox illuminates the result of selfish choices in self-organizing networks. Let’s say you have a crowded network of roads. A new road opens up that appears to offer a faster route. Driver makes selfish choices and head to the new road, making it more crowded while not appreciably alleviating the rest of the network. The result: on average, it takes longer to get to the destination. (Conceptually, this seems similar to the paradox known as the tragedy of the commons).

Does it work? Well, in 1990 New York City temporarily closed 42nd Street, a major thoroughfare. People predicted disaster but traffic actually flowed more smoothly. In 2011, Los Angeles closed a ten-mile stretch of freeway for construction and predicted a traffic “jam of biblical proportions” (known sardonically as Carmaggedon). It turned out to be not so bad.

The paradox may also happen in other self-organizing networks, like your brain. New Scientist reports that certain brain injuries can result in loss of vision. Surprisingly, creating another lesion in another part of the brain can help restore partial vision. Nobody understands exactly why but, apparently, the new lesion removes links in the network and helps the overall network improve its performance.

The same phenomenon can affect your ability to make optimal choices. Let’s say you’re going to by a new car. To find the best one for your needs, you decide to closely review 1,000 makes and models. The result? You’re quickly overwhelmed. To improve performance, it’s better to winnow the field and evaluate fewer options rather than more.

Sports analysts believe that the paradox may also pertain to team sports. Some teams play better when their star player(s) is removed from the game. Why would that be? Think of a team as a network. The ball often moves to (and sometimes from) the star player in the network. The path to and from the star is the most heavily travelled link in the network. Removing that link means the network has to reorganize and redistribute. That can result in improved performance.

I think we saw Braess’s paradox in the Denver Broncos’ defense this past season. Many observers consider Von Miller the best player on the Broncos’ defense. Miller was suspended for the first six games of the season. When Miller did not play, the Broncos actually recorded more sacks per game (a key defensive statistic) than they did when Miller played. In other words, the network reorganized itself and performed better.

Braess’s paradox may be very good news for the Broncos in the upcoming Super Bowl. The team has lost a number of key defensive players (including Miller) to injury. As the defensive network reorganizes itself, its performance may well improve. We already know that the Broncos have an unstoppable offense. As Braess’s paradox works its magic on the defense, the team is almost guaranteed a victory.

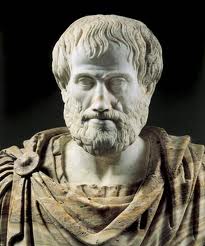

Aristotle and Economics

He’s back!

The Nobel economist, Robert Shiller, has an interesting assessment of economics in yesterday’s New York Times. Shiller is one of three economists to win the prize this year and they all have different opinions on rationality and economics.

Prizewinner number one, Eugene Fama, is a rationalist. Rational people making rational economic decisions can explain all of economics. You have to look closely, but it’s all rational. Prizewinner number two, Lars Peter Hansen, occupies a middle position, emphasizing mathematical models but also noting the importance of “animal spirits, … rare events, and overconfidence….”

Shiller (aka prizewinner number three) notes that he is “the most willing … to incorporate ideas about nonrational or irrational behavior from other social sciences….” I’ve written a bit about nonrational economic behaviors – like loss avoidance bias. Additionally, I know that I don’t always make decisions solely for the purpose of maximizing my income. In other words, they’re nonrational in the strictest sense of economic rationality. So, I’m probably in Shiller’s camp.

Ultimately, however, I think the debate goes all the way back to Aristotle who made a clear distinction between:

- Things that can never be other than they are, and:

- Things that can be other than they are.

Physics is in Category One. The speed of light won’t change, no matter how much we discuss it. Thus, Aristotle proposes that analytics are the appropriate tools to study physics – and any other topic that falls in Category One. We analyze to understand, not to change things. By understanding, we may improve our ability to adapt to the world, but we’re not changing the world. (On related topic, I worry that physics envy is leading economists astray. The economists are being nonrational).

On the other hand, Aristotle would put political science in Category Two. The way we govern ourselves can be changed and improved. We need to analyze but we also need to come to a consensus. Aristotle codified rhetoric for this purpose. Rhetoric is the art and science of persuasion with the goal of reaching consensus on how we can improve the world around us. Rhetoric is not simply the art of winning an argument (that’s sophistry). Rhetoric helps us think clearly, reason together, and change what can be changed to build a better world.

I’ve been wondering recently whether economics fits into Category One or Two. If it’s Category One, all we can do is analyze it. We can describe economics but we can’t change it to build a better world – except in the sense that we can understand the world better. If economics is in Category Two, however, we could conceivably identify better ways to organize our economies and improve the world around us.

If economics is totally rational, then it seems to fit into Category One. We can only describe it. There’s no changing it (unless we can change human rationality, which seems improbable).

On the other hand, if economics has nonrational elements, then we could conceivably improve it. We could identify mechanisms that would help us balance rational and nonrational behaviors. As Shiller notes, he still advocates “a free market system, with innovations to make it work better.” I’m an optimist, so I’m hoping that economics fit naturally into Category Two. That’s why I’m lined up with Shiller (and Kahneman and others).

Aristotle has given us an interesting system to organize our thoughts. So what do you think? Does economics fit in Category One or Category Two?

Stemming the STEM Tide

Can we make science fun?

I sometimes get a bit depressed when reading about scholastic achievement in America. For instance, in the 2012 edition of the PISA tests (Program for International Student Achievement) American teenagers ranked as average or below average in math, science, and reading. (The test measures achievement for 15-year-olds).

The Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a group of 34 mostly first-world countries, administers PISA every three years. In addition to the member states, other countries can also request to take the tests. In 2012, 65 countries participated. Compared to the 65 countries, the USA ranked

- 30th in math;

- 23rd in science, and;

- 20th in reading.

Since OECD first administered the tests in 2000, American performance has not changed much. Our relative position, however, has fallen as other countries have passed us by. Arne Duncan, our Secretary of Education, says that the results “must serve as a wake-up call” for the nation. (Here’s a good infographic on the results. Here’s an in-depth report from OECD.)

But is it really a crisis? Sure, it would be great to be number one in everything, but if we had to choose, would it be better to be first in teen achievement or in national achievement? According to the Bloomberg Innovation Quotient, for instance, America is the most innovative country in the world. The Global Innovation Index is a little less sanguine, but still ranks the USA as the fifth most innovative nation in the world.

It appears, then, that poor adolescent performance doesn’t lead directly to poorer national performance. Though our 15-year-olds are average (at best) perhaps our 21-year-olds are not. Perhaps our colleges and universities are picking up the slack. Perhaps innovation stems from creativity more than mastery of science, math, and reading. Perhaps our national diversity creates opportunities that are not found in more homogeneous countries. Perhaps … well, there are so many variables that it’s hard to sort them out.

In a related field, we’ve seen a lot of handwringing about STEM in America. STEM includes all disciplines in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math. Over the past several decades, critics have suggested that we’re recruiting too few students into STEM fields and that too many are dropping out. As with the PISA scores, analysts suggest that a crisis is brewing and must be fixed or we’ll inexorably decline as a nation.

Really? A recent article in Science magazine points out that “…new data poke major holes in the conventional wisdom.” For instance, conventional wisdom holds that the attrition rate for STEM students is very high. Indeed, as many as 50% of STEM students drop out or switch to non-STEM majors. That does sound high but nobody had researched the attrition rate in other disciplines. When researchers actually looked at other fields, they found the attrition rate in the humanities was 56% and in business was 50%. In other words, students really aren’t very good at deciding what to major in when they first arrive at university.

Conventional wisdom also holds that very few students transfer to STEM majors. STEM is characterized by “low inflow and high outflow”. But a study from Indiana University suggests otherwise. Of students who entered college expecting to major in a STEM field, 24% changed to a non-STEM field by the end of their first year. That sounds like a lot but the study also found that 27% of students who entered college in a non-STEM field had transferred to a STEM curriculum in their first year. As the Science article concludes, it’s a two-way street.

What does all this mean? I think it’s time to put on our critical thinking caps, step back, take a deep breath, and define the problem more clearly. I’m not arguing that there’s no problem. But I do believe that we’ve defined the problem incorrectly.