Just Add Women

You doubt my effectiveness?

Germany is poised to join the 30 Percent Club. Beginning in 2016, women must hold at least 30 percent of board seats at large, public companies. Germany will join other countries like Norway, France, Spain and the Netherlands in mandating female representation on boards of directors.

Will it work? It depends on what the goal is. Norway began the trend in 2006, mandating 40% representation. As The Economist puts it, “…[the] law has not been the disaster some predicted.” Not exactly a ringing endorsement but the magazine suggests that the real benefit may be a change in attitude.

The Financial Times appears a bit more optimistic: “Early analysis appears to show that quotas work and have been highly successful across Europe.” Fortune appears less sanguine, “a close look at the results of these quotas – and of Norway’s in particular, which have been in effect the longest – shows that the results might not be all that their backers intend.” Fast Company is more positive.

The articles I’ve cited here seem to have different views of what success means. If success is defined as:

- More female representation on boards, then the quotas work.

- Better financial and stock performance, then the results are decidedly mixed.

- Fewer layoffs, then the quotas seem to work.

Unfortunately, none of the articles discuss why boards with women might perform better. I’ve found two different reasons in the literature that suggest that women can bring important qualitative differences to board discussions and decisions.

First, women appear to make better decisions about risk, especially under stress. The research comes from Mara Mather and Nicole Lighthall who study the effects of stress on decision-making. They found that stress changes the way we select alternatives and accentuates differences between men and women. Bottom line: “…stress amplifies gender differences in strategies during risky decisions, with males taking more risk and females less risk under stress.”

Why would that be? Writing in the New York Times, Therese Huston argues that it may be empathy. We generally view women as more empathetic than men. Under stress, Huston writes, women “… actually found it easier than usual to empathize and take the other person’s perspective. Just the opposite happened for the stressed men — they became more egocentric.”

The second major reason stems from the impact of women on group behavior and effectiveness. MIT reports that the “tendency to cooperate effectively is linked to the number of women in a group.” In The Atlantic, Derek Thompson writes that group intelligence is similar to general intelligence in an individual. General intelligence suggests that an individual who is good at one thing is likely to be good at other things as well. Similarly, a group that’s good at one thing is likely to be good at other things, too. This is dubbed collective intelligence, which varies from group to group.

What factors contribute to collective intelligence? It’s not the average intelligence of the people in the group. Nor is it the intelligence of the smartest person. Thompson notes that we can rule out many other things as well, including motivation, cohesion, and employee satisfaction.

So what makes a group collectively intelligent? Average social sensitivity. It’s the ability to read between the lines and understand what someone is really saying. Thompson writes, “social sensitivity is a kind of literacy, and it turns out that women are naturally more fluent in the language of tone and faces than the other half of their species.”

So women make better decisions in stressful situations. Boards have to deal with high levels of stress. Women also make groups more effective. Boards, of course, are groups of people trying to reach effective decisions. The debate on women on boards was generally framed by the question: Why would we put women on boards? With our new understanding, the proper question is: why wouldn’t we?

(The New York Times also has an interesting on group effectiveness and female participation. Click here.)

Groups Get It Wrong (All Too Often)

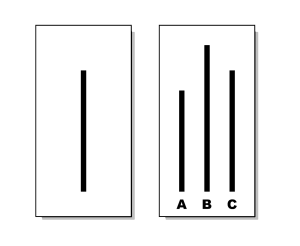

The right answer is obviously B.

Why do decisions go wrong? Many times, it’s because the decision is made by a group, not by an individual. Individuals tend to look at the evidence and make a decision. It may not be the right decision but it’s often based on an assessment of the facts.

Groups may assess the facts as well but they also assess the politics of the situation. The issue may be decided on group dynamics rather than a dispassionate review of the evidence.

Bain & Company recently published a white paper (Decision Insights: How Group Dynamics Affect Decisions) that provides a useful summary of the issues. Here are four ways, for instance, that group dynamics can lead to debacles.

Conformity – if you’re a team player, you may go with the team’s decision even if you realize it’s wrong. The graphic above shows Solomon Asch’s classic experiment. Which line – A, B, or C – is the same length as the line to the left? Working alone, you’ll probably figure out that C is the right answer. However, if you’re in a group that says B is the right answer, you’re quite likely to go with the group. Many companies say they want team players, but they need to be aware of the implications. (See also Group Behavior – The Risky Shift.)

Group Polarization – let’s assume for a moment that you belong to a politically conservative group. You talk to conservatives regularly. Indeed, you talk only to conservatives. You reinforce each other and the group gets more and more conservative. In many cases, the group becomes more conservative than any of its individual members. (See also, Will The Internet Cause Dementia? and Where You Stand Depends on Where You Sit.)

Obedience to Authority – the quickest way to stifle innovation is to let the boss speak first. We all want to please our bosses, so if the boss expresses a preference for X over Y, we often begin to find reasons why X is indeed better than Y. It’s hard to argue with your boss … unless you’re specifically asked to play the role of devil’s advocate, which is often a good idea. Note to bosses: keep quiet. (See also, Want A Good Decision? Go To Trial.)

Bystander Effect – when we’re not sure what to do, we often look to others to see what they’re doing. If they’re panicking, we get panicky. If they’re cool, calm, and collected, we calm down (even if we think we should panic). Individuals often understand a situation better than groups do which is why you should never have a heart attack in a crowd.

So, what to do? Diversity in a group often helps overcome groupthink and polarization, so pull people together from different backgrounds and risk profiles. Playing roles can help. You might stage a mock trial or ask someone to play the devil’s advocate. You can also ask each individual to write down his or her recommendation anonymously, put them all in a hat, and then discuss all of them. You can also prime the team by discussing what it means to be a team player. Emphasize the need to make the best decision, not just the most comfortable one.

And, if all else fails, just ask the boss to leave the room.