Context Effects: PayPal and Brexit

Whom do you trust?

PayPal was recently skewered on social media because it sponsored a panel discussion on gender equality and inclusion in the workplace. The problem was that the panel consisted solely of men. Women quickly tore into the company on Twitter and Tumblr for being tone deaf and sexist.

In fairness to PayPal, the panel discussion was supposed to have been titled: “Gender Equality and Inclusion In the Workplace: A Conversation With Our Male Allies”. Somehow, the organizers omitted the last part of the title from the official program.

I suspect that PayPal’s panel was a well-intentioned effort to bridge the gender gap. But the organizers made a simple mistake – they focused on strategy and forgot about context.

In persuasion, we typically start by developing the message strategy. What is the key message that we need to communicate? How can we best encapsulate that message in a memorable campaign?

While message strategy is certainly critical, it’s not the only concern. We also need to consider the context the message is delivered in. It’s a fairly simple question: does the context create an opportunity to deliver our message effectively? Sometimes, contextual factors facilitate the message delivery. At other times, the context constrains our ability to communicate clearly. Creating an all-male panel on gender equality does not provide a favorable context.

From a timing perspective, Greek rhetoricians called this kairos. Translated literally, it means the “supreme moment”. In our context, kairos means finding the opportune moment to deliver a persuasive message. As Jay Heinrichs points out, it’s analogous to a teachable moment. A teacher finds the right moment to teach a memorable lesson. Similarly, a persuader finds the right moment to deliver a persuasive message.

Kairos refers to timing and timeliness. But we need to consider other contextual factors as well. Who delivers the message? In what forum? What is the audience ready to receive? Whom does the audience trust? What media and channel provide the best opportunity to deliver the message successfully?

In this context, I wonder about the Brexit campaign in the United Kingdom. One side – the Remain campaign — argues that Britain will be stronger by staying in Europe. The other side – the Leave campaign — argues that leaving will make Britain great again. Both sides have worked out their message strategies.

Polls suggest that the two sides are very evenly divided. Both sides have strong messages. Neither has a clear advantage. Given this, which side will be more persuasive? In my humble opinion, it will be the side that makes best use of contextual factors. In this regard, the Leave campaign has a clear advantage.

While the Remain campaign has a solid message, it’s misreading the context. More specifically, it’s using the wrong messengers (again, in my humble opinion).

Here’s the context. Voters who support the Leave campaign perceive that their economic situation has deteriorated since Britain joined the European Union. They also perceive that joining the Union was a project conceived and championed by the “elite”. It’s easy to conclude that the elite classes have “sold us out”.

And who is speaking for the Remain campaign? By and large, it’s the elite. We hear from top managers, bankers, executives, rich people, and assorted toffs. We even hear from the head of the IMF, who happens to be French. Now, we even hear from the president of the United Sates.

Who are these people? They’re the elites – exactly the people whom the Leavers don’t trust. The easy response from the Leave campaign: “Well, you remember what happened the last time we trusted them.”

If the Remain campaign continues to pursue an elite strategy, I suspect the Leave campaign will win – and by a wide margin. What’s the lesson in all this? Whether you’re PayPal or the British Prime Minister, consider the context.

Rhetorical Jujitsu

Lovely place Brixham

The United Kingdom is deeply embroiled in the Brexit debate. It’s the classic question: should we stay or should we go? Polls suggest that the electorate is almost evenly split. What can this teach us about persuasion?

Let’s take an example from a man with an opinion. Michael Sharp is a fisherman from the lovely little port of Brixham on the south coast of England who favors leaving the EU. The New York Times quotes him as saying,

“I definitely want out. … All those wars we’ve had with France, Germany — all the rest of them since God knows when, since Jesus was a lad — we’re never going to get on with them, are we?”

Now imagine that you support the opposite side – you think the UK should stay in the EU. How might you persuade Mr. Sharp to agree with you? Here are four different rhetorical approaches you might try:

A) “What a silly thing to say. We’re friends with France and Germany now. You’re 70 years out of date.”

B) “What a parochial and small-minded attitude you have. You should broaden your horizons.”

C) “All the experts say we should stay in. The top bankers and managers say it will wreck the economy to leave.”

D) “I know what you’re saying. But I’ll tell you what I’m worried about. The Russians. If we’re squabbling with the French and Germans, the Russians will divide and conquer. That’s what they’re good at. It’ll be worse for all of us.”

Which alternative is best? As always, it depends on what you want to accomplish. Let’s look at the choices.

Alternatives A & B – in both cases, you strongly suggest to Mr. Sharp that he’s wrong, stubborn, and not very smart. If your goal is to feel superior to Mr. Sharp, this is a good strategy. On the other hand, if wish to persuade Mr. Sharp to your way of thinking, you’ve just shot yourself in the foot.

Alternative C – an appeal to authority can work in some situations. But not here. Many Brexit supporters think the authorities – better known as the elites – can’t be trusted. “They don’t care about us. They’ve sold us out. If they say we should stay, all the more reason to leave.” In this case, quoting the elites is self-defeating. (It’s probably a poor tactic in arguing with a Donald Trump supporter as well).

Alternative D – this is a rhetorical technique known as concession-and-shift. You begin by agreeing with the other person. In this case, you concede that Mr. Sharp is right. This makes you seem open-minded and reasonable (even if you’re not). Then you shift to new ground and bring in a different perspective. Since you’re open-minded, Mr. Sharp is more likely to be open-minded in return. He’s more likely to listen to your thoughts and understand your position. That’s the first step in persuading him to your point of view.

Concession-and-shift is a form of rhetorical jujitsu. You don’t push back. You don’t deny the other person’s position. You don’t try to humiliate the other side. Rather, you accept their position and move on. In its simplest form, you say, “You have a good point. But have you considered …”

Concession-and-shift can work in many different situations. It’s a useful tool to master and remember. And it helps us achieve the ultimate goal of rhetoric – to argue without anger.

Always Be Conversing

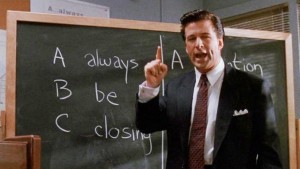

He was so young!

In the 1992 movie, Glengarry Glen Ross, Alec Baldwin played a very hard-nosed sales manager determined to teach a bunch of rookies how to sell. He used intimidation, fear, stress, and money as motivators. He didn’t believe in being nice. He believed in closing.

Baldwin also introduced a term that I’ve heard many times since: Always Be Closing or ABC. The idea is simple – you’re always looking for prospects, qualifying them, moving them through the sales process, and closing them. Then you start over. You’re like a shark – always moving, always eating.

Always Be Closing is associated with pushy, high-pressure sales tactics. You might find them in use at car dealerships or time-share condo conventions. We’re all familiar with them and we all profess to hate them.

Now what about nonprofits? Is Always Be Closing an appropriate technique for raising funds for a nonprofit organization? I don’t think so. For me, nonprofit fundraising is all about relationships. It’s about building for the long run, not closing in the short term.

So I’ve created a new ABC for non-profits: Always Be Conversing. A conversation, of course, has two parts: talking and listening. Always Be Conversing suggests that we’re always ready to talk about our nonprofit organization (NPO) and listen to our constituents’ needs. By conversing with constituents, friends, and our broader network of acquaintances, we build relationships. Over time, those relationships allow us – quite naturally – to ask for donations.

Always Be Conversing also implies that we actively seek out conversations. To create rich conversations, we need to prepare ourselves. Here are some pointers:

- Always have a story – people love stories – they’re easy to understand, relatable, and memorable. When you tell a story, you’re not being a pushy sales person. Rather, you’re building relationships, awareness, and interest. Tip: focus on outputs, not inputs. If your NPO donated a million dollars for scholarships last year, that’s an input. It’s an interesting fact but not a story. On the other hand, if you can describe how your scholarships changed people’s lives, that’s the output of your investment. It’s also a memorable story that most people will be eager to hear.

- Use conversation starters – how does anyone know that you’re passionate about your NPO? How does anyone know that you’re a source of information and assistance? The simplest way is to wear some identification. If you wear a lapel pin or a brooch or a jacket with your NPO’s logo on it, people can identify you and have a conversation. It can happen at random times, so always have a story ready.

- Don’t ask, offer– my NPO is the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. When I wear my NMSS jacket to the grocery store, people frequently ask me about my connection to the Society. Then they often say, “My (wife, cousin, mother, neighbor, etc.) has MS.” I typically respond by saying, “How can I help?” As it happens, NMSS can help in a variety of ways, from insurance advice to exercise programs. But I’m also invoking the reciprocity principle – you’re more persuasive if you offer a favor before requesting a favor.

Over the coming weeks, I’ll write more about fundraising for nonprofits through story telling and relationship building. In the meantime, start telling your stories. You’ll be surprised at the impact you can have.

(My NPO is the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. If you need information about multiple sclerosis or help in dealing with it, just drop me a line. I want to Always Be Conversing).

The Curse of Knowledge

You know too much.

Long ago, when I was a product manager at NBI, I gave a speech on local area networks (LANs) at a customer conference. LANs were just becoming popular at the time and industry analysts were debating which standards would prevail.

NBI was betting on a standard called CSMA/CD. IBM was betting on token ring. The objective of my speech was to persuade the audience that CSMA/CD was the better choice and, therefore, more likely to prevail in the long run. Token ring, on the other hand, was risky and might become a dead end product – much like IBM’s OS/2 operating system.

I knew the technology cold and I gave a great speech if I do say so myself. I highlighted the technology advantages of CSMA/CD. I set criteria around the key functions that CSMA/CD could perform and token ring couldn’t. I know that most audiences admire IBM so I didn’t take any cheap shots at Big Blue. A cheap shot would weaken my credibility, not theirs.

At the end of the speech, I was busy patting myself on the back when a very nice woman came up and asked a simple question: “What’s a LAN?” Throughout my speech, I had defined an array of advanced technical concepts but had forgotten to define the basics. My face turned red as I realized that I had just made the rookiest of rookie mistakes. I had asked the audience to come to my house rather than going to their house.

In the trade, this is known as the curse of knowledge. I knew the audience wouldn’t know the finer points of CSMA/CD but I assumed – erroneously – that they grasped the basics. I didn’t need to explain them. I never even thought about it.

In Made To Stick, the Brothers Heath tell the story of “tappers” and “listeners” which was the subject of Elizabeth Newton’s dissertation in psychology. Tappers received a list of popular songs and were asked to tap out the song on a tabletop. No whistling or humming allowed; just tap on the table. Listeners were supposed to guess the song.

Tappers were confident that they could convey the song successfully at least 50 percent of the time. But, in fact, listeners guessed the song correctly only 2.5 percent of the time.

Why were the tappers so confident? Because they could hear the song in their head. They heard the taps but they also heard so much more. As the Heaths point out, “Once we know something, we find it hard to imagine what it was like not to know it. Our knowledge has ‘cursed’ us. And it becomes difficult for us to share our knowledge with others, because we can’t readily re-create our listeners’ state of mind.”

When I gave my speech on LANs, I could hear the entire song in my head. I knew how it sounded. I knew how to orchestrate it. I knew where to pause. I knew where to put in jokes. I knew it cold.

The only thing I didn’t know was what was in my audience’s head. That’s the curse.

Chris Christie: The I Guy

Me, myself, and I

In my video, Five Tips for the Job Interview, my first tip is to be careful how often you say “I” as opposed to “we”. If the company you’re interviewing with is looking for team players — and many companies say they are — then saying “I” too often can hurt your chances. You can come across as self-centered and egocentric. Someone, in other words, who doesn’t play well with others.

I thought about this tip the other day when I watched Chris Chrstie’s press conference addressing the bridge closure scandal. (If you haven’t heard about it, you can get a good summary here). As the Republican governor of a very Democratic New Jersey, Chritsie is widely regarded as an appealing candidate for the Republican nomination for president in 2016. In a way, he’s interviewing for the biggest job of all. Perhaps he should have watched my video.

In the press conference, Christie needed to address a scandal that appears to be about naked political payback. The Democratic mayor of Fort Lee, New Jersey didn’t endorse Christie for governor in the recent campaign. As a result (it appears), Christie’s minions shut down traffic in Fort Lee for four days. Christie needed to apologize and distance himself from such nasty political deeds.

Dana Milbank, a columnist for the Washington Post, paid close attention to the press conference. In fact, he went through the transcript and analyzed Christie’s language. The press conference lasted 108 minutes; Christie said some form of “I” or “me” (I, I’m, I’ve, me, myself) 692 times. That’s 6.4 times per minute or a little more than once every ten seconds.

The net result is that Christie comes across as an egomaniac. That may be the case but, generally, you don’t want to come across that way in an important interview. There’s a lot that I like about Governor Christie — he seems to be one of the few politicians in America who can actually pronounce the word “bipartisan”. I hope he can learn to pronounce “we” and “you” as well.