Arguments and Sunk Costs

Why would I ever argue with her?

Let’s say that Suellen and I have an argument about something that happened yesterday. And, let’s say that I actually win the argument. (This is highly theoretical).

The Greek philosophers who invented rhetoric classified arguments according to the tenses of the verbs used. Arguments in the past tense are about blame; we’re seeking to identify the guilty party. Arguments in the present tense are about values – we’re debating your values against mine. (These are often known as religious arguments). Arguments in the future tense are about choices and actions; we can decide something and take action on it. (Click here for more detail).

In our hypothetical situation, Suellen and I argue about something in the past. The purpose of the argument is to assign blame. I win the argument, so Suellen must be to blame. She’s at fault.

I win the argument so, bully for me. Since I’ve won, clearly I’m not to blame. I’m not the one at fault. I’m innocent. Maybe I do a little victory dance.

Let’s look at it from Suellen’s perspective. She lost the argument and, therefore, has to accept the blame. How does she feel? Probably not great. She may be annoyed or irritated. Or she might feel humiliated and ashamed. If I try to rub it in, she might get angry or even vengeful.

Now, Suellen is the woman I love … so why would I want her to feel that way? If someone else made her feel annoyed, humiliated, or angry, I would be very upset. I would seek to right the wrong. So why would I do it myself?

Winning an argument with someone I love means that I’ve won on a small scale but lost on a larger scale. I’ve come to realize that arguing in the past tense is useless. Winning one round simply initiates the next round. We can blame each other forever. What’s the point?

In the corporate world, the analogue to arguing in the past tense is known as sunk costs. Any good management textbook will tell you to ignore sunk costs when making a decision. Sunk costs are just that – they’re sunk. You can’t recover them. You can’t redeem them. You can’t do anything with them. Therefore, they should have no influence on the future.

Despite the warnings, we often factor sunk costs into our decisions. We don’t want to lose the money or time that we’ve already invested. And, as Roch Parayre points out in this video, corporations often create perverse incentives that lead us to make bad decisions about sunk costs.

Our decisions are about the future. Sunk costs and arguments about blame are about the past. As we’ve learned over and over again, past performance does not guarantee future results. We can’t change the past; we can change the future. So let’s argue less about the past and more about the future. When it comes to blame or sunk costs, the answer is simple: Don’t cry over spilt milk. Don’t argue about it either.

Mind and Body

Happy Girl

How much does your body affect your brain? A lot more than we might have guessed even just a few years ago. The general concept — known as embodied cognition – holds that the body and the brain are one system, not two. (Sorry, Descartes). What the body is doing affects what the brain is thinking.

I’ve written about embodied cognition before (here and here). Recently, I’ve seen a spate of new stories that extend our understanding. Here’s a summary:

The power pose – want to perform better in an upcoming job interview? Just before the interview, strike a power pose for two minutes. Your testosterone will go up and your cortisol will go down. You’ll be more confident and assertive and knock ’em dead in the interview. Amy Cuddy explains it all in the second most-watched TED video ever.

Willpower, dissension, and glucose – If you run ten miles, you’ll deplete your energy reserves. You may need to relax and refuel before taking up a new physical challenge. Does the same thing happen with willpower? Apparently so. If you resist the temptation to smoke a cigarette, you’ll have less willpower left to resist eating a donut. You can use up willpower just like you use up physical power. Perhaps that’s why you’re more likely to argue with your spouse when your glucose levels are low. If you sip a glass of lemonade, you might just avoid the argument altogether.

Musicians have better memories – experiments at the University of Texas suggest that professional musicians have better short- and long-term memories than the rest of us. For short-term memory (working memory), the musicians are better at both verbal and pictorial recall. For long-term memory, they’re better at pictorial recall. Maybe we should invest more in musical education.

How you walk affects your mood – as the Scientific American points out, “A good mood may put a spring in your step. But the opposite can work too: purposefully putting a spring in your step can improve your mood.” As Science Daily points out, the opposite is also true. If you walk with slumped shoulders and head down, you’ll eventually get grumpy. Your Mom was right: standing up straight actually does affect your mood and performance.

Intuition may just be your body talking to you – when you get nervous, your palms may start to sweat. Your mood is affecting your body, right? Well, maybe it’s the other way round. Your intuition (also known as System 1) senses that something is amiss. It needs to get your (System 2) attention somehow. What’s the best way? How about sweaty palms and a racing heartbeat? They’re simple, effective signaling techniques that are hard to ignore.

The power of a pencil – want to get happy? Hold a pencil in your mouth like the woman in the picture. Your facial muscles act as if they’re smiling. You may consciously realize that you’re not smiling but it doesn’t really matter – your body is doing the thinking for you.

Reality Is A Conspiracy

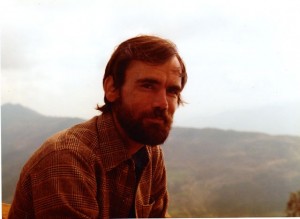

I want my sweater.

In 1973, when I lived in Ecuador, I survived two nasty accidents within the space of a few days. First, I slid off a glacier and fell roughly 90 feet while climbing in the Andes. I landed in soft snow and wasn’t hurt. A few days later, I flipped over in a Land Rover while driving a mountain road with a friend. The vehicle flipped onto its top, then flipped again and landed on its wheels. My friend and I got out, taped up some broken windows, and drove on.

How could I survive two near-fatal accidents in less than a week? My lucky sweater saved me.

A few days after the flying Land Rover incident, I conducted a mental inventory of everything I had been wearing in the two accidents. The only garment that I had on in both cases was a beat-up old climbing sweater. Clearly, the sweater had protected me from serious harm.

From that point on, I wore the sweater whenever I went climbing. I became quite superstitious about its protective powers. I knew I would be safe as long as it was close to me.

Was my interpretation of reality correct, objective, and reasonable? Most of us would say no. But the pioneering sociologists (and married couple), William and Dorothy Thomas say that it just doesn’t matter. According to the Thomas Theorem, first proposed in the 1920s: “It is not important whether or not the interpretation is correct – if men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.”

The Thomas Theorem can help us understand a range of topics, including conspiracy theories, availability cascades, and self-fulfilling prophecies. We all believe in conspiracy theories of one sort or another. Right-wingers may believe that global warming is a hoax. Left-wingers may believe that big business is a vast conspiracy of the rich against the poor. Whether or not the interpretations are correct, both left- and right-wingers act as if they are real. Their beliefs are real in their consequences.

If we don’t believe in a particular conspiracy theory, it seems completely irrational to us. How could anyone believe that? Anyone who does believe it must be a craven fool. If we know such people, we may try to talk them out of it. We deploy our best logic and most compelling arguments. Typically, we fail to convince them. In fact, we may just cause them to harden their position.

We fail because we misunderstand the nature of conspiracy theories. We think of them as flawed logic (at least, those we disagree with). But in reality, a conspiracy theory is simply a different view of reality. We all have models of reality in our heads. We all want to explain why things are. While all of our models are different, we each believe that our model is accurate. Some of us use theories of history to explain why things are the way they are. Others use religion or Marxism or astrology or conspiracy theories. We all have a belief system that explains everything to our satisfaction.

So how do you change a friend’s belief system? It’s not by arguing logically. Your logic doesn’t apply to his reality. The best approach I’ve found is to ask him to explain how the world works. Don’t ask why he believes it. Ask how it all fits together.

Chances are your friend’s theory of the world doesn’t fit together seamlessly. He probably can’t explain things as thoroughly as he thinks he can. He’s suffering from the illusion of explanatory depth. When he stumbles, he may realize that his theory isn’t coherent and exhaustive. Use questions rather than arguments; let him discover the discrepancies on his own. You won’t convince him otherwise.

Go ahead and give it a try. It may not work but it’s the only technique that has a chance. Just don’t try to take away my sweater.

Ebola and Availability Cascades

We can’t see it so it must be everywhere!

Which causes more deaths: strokes or accidents?

The way you consider this question speaks volumes about how humans think. When we don’t have data at our fingertips (i.e., most of the time), we make estimates. We do so by answering a question – but not the question we’re asked. Instead, we answer an easier question.

In fact, we make it personal and ask a question like this:

How easy is it for me to retrieve memories of people who died of strokes compared to memories of people who died by accidents?

Our logic is simple: if it’s easy to remember, there must be a lot of it. If it’s hard to remember, there must be less of it.

So, most people say that accidents cause more deaths than strokes. Actually, that’s dead wrong. As Daniel Kahneman points out, strokes cause twice as many deaths as all accidents combined.

Why would we guess wrong? Because accidents are more memorable than strokes. If you read this morning’s paper, you probably read about several accidental deaths. Can you recall reading about any deaths by stroke? Even if you read all the obituaries, it’s unlikely.

This is typically known as the availability bias – the memories are easily available to you. You can retrieve them easily and, therefore, you overestimate their frequency. Thus, we overestimate the frequency of violent crime, terrorist attacks, and government stupidity. We read about these things regularly so we assume that they’re common, everyday occurrences.

We all suffer from the availability bias. But when we suffer from it simultaneously and together, it can become an availability cascade – a form of mass hysteria. Here’s how it works. (Timur Kuran and Cass Sunstein coined the term availability cascade. I’m using Daniel Kahneman’s summary).

As Kahneman writes, an “… availability cascade is a self-sustaining chain of events, which may start from media reports of a relatively minor incident and lead up to public panic and large-scale government action.” Something goes wrong and the media reports it. It’s not an isolated incident; it could happen again. Perhaps it could affect a lot of people. Perhaps it’s an invisible killer whose effects are not evident for years. Perhaps you already have it. How would one know? Or perhaps it’s a gruesome killer that causes great suffering. Perhaps it’s not clear how one gets it. How can we protect ourselves?

Initially, the story is about the incident. But then it morphs into a meta-story. It’s about angry people who are demanding action; they’re marching in the streets and protesting in front of the White House. It’s about fear and loathing. Then experts get involved. But, of course, multiple experts never agree on anything. There are discrepancies in the stories they tell. Perhaps they don’t know what’s really going on. Perhaps they’re hiding something. Perhaps it’s a conspiracy. Perhaps we’re all going to die.

A story like this can spin out of control in a hurry. It goes viral. Since we hear about it every day, it’s easily available to our memories. Since it’s available, we assume that it’s very probable. As Kahneman points out, “…the response of the political system is guided by the intensity of public sentiment.”

Think it can’t happen in our age of instant communications? Go back and read the stories about ebola in America. It’s a classic availability cascade. Chris Christie, the governor of New Jersey, reacted quickly — not because he needed to but because of the intensity of public sentiment. Our 24-hour news cycle needs something awful to happen at least once a day. So availability cascades aren’t going to go away. They’ll just happen faster.

Are We Done Yet?

Is it done yet?

A few years ago, I asked some artist friends, “How do you know when a painting is finished?” By and large, the answers were vague. There’s certainly no objective standard. Answers included, “It’s a feeling…” or “I know it when I see it.” One friend confessed that, when she sees one of her paintings hanging in a friend’s house – even years after she “finished” it – she’s tempted to take out her brushes and continue the process. The simplest, clearest answer I got was, “I know it’s done when I run out of time.”

I thought of my artist friends the other night when I heard Jennifer Egan give a lecture at the Pen and Podium series at the University of Denver. Egan, who won a Pulitzer Prize for her novel, A Visit From The Goon Squad, spoke mainly about her craft – how she develops her ideas, characters, and plots. While she’s probably best known for her novels, Egan also writes long-form nonfiction, mainly for the New York Times Magazine.

Interestingly, Egan uses different writing processes for fiction and nonfiction. For nonfiction, she uses a keyboard. For fiction, she writes it out longhand. She said, “I write my fiction quickly and in longhand because I want to write in an unthinking way.” It sounds to me that she writes her fiction from System 1 and her nonfiction from System 2. I wonder how common that is. Do most authors who compose fiction, write from System 1? Do authors of nonfiction typically write from System 2? (For the record, I write nonfiction and I write in System 2; I’m not sure how to write from System 1).

Egan went on to say that she follows a simple three-step process in her writing: “Write quickly. Write badly. Fix it.” She captures the essence of her idea quickly and then revisits it to clean and clarify her thoughts. I wonder how she knows when she’s finished.

I thought of Egan the other day when I was reading about Google’s management culture. One of Google’s mottos is, “Ship then iterate.” The general idea is to get the software into reasonably good shape and then ship it to customers. (You may want to call it a beta version). Once the software is in customer hands, you’ll find out all kinds of interesting things. Then you iterate with a new release that adds new features or fixes old ones. The point is to do it quickly and do it frequently. It sounds remarkably similar to Jennifer Egan’s writing process.

There’s a corollary to this, of course: your first draft or first release is not going to be very good. Egan told the story of the first draft of her first novel. It was so bad, even her mother wouldn’t return her calls. In the software world, we say something quite similar, “If you’re proud of your first release, you shipped it too late.”

Software, of course, is never finished. You can always do something more (or less). I wonder if the same isn’t true of every work of art. There’s always something more.

While you could always do something more, the trick is to get the first draft done quickly. Create it quickly. Think about it. Fix it. Repeat. It’s a good way to create great things.