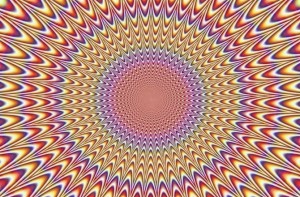

Naive Realism and Open Mindedness

It’s an apple!

We all think that what we see is real. If I see an apple in front of me, it’s because there really is an apple in front of me. Under different lighting conditions, however, the apple may change colors or even its shape. I may see part of it and assume that the rest of it is there.

Further, I may perceive it quite differently when I’m hungry than when I’m full. Other people may see the apple differently than I do. They may perceive different shapes or colors. They may recognize that it’s a rare heirloom apple and have a much different experience of it than I do.

Or, I may be distracted (inattentional blindness) and not see the apple at all. Does the apple disappear from reality or just my perception of reality?

In my critical thinking classes, I ask students to wander around our building and observe the architecture. When they return to class, I ask if they could confidently describe what they saw. The typical answer is “Sure, why not?” Then I ask each student to draw a map. As you can probably guess, the maps don’t even remotely resemble each other. So, which student saw reality?

In truth, we build little models of reality in our heads. Suellen’s model includes a lot of plants. Mine includes fewer plants and more cars. Our models are different. We literally see different things. But she’s very confident that what she’s seeing is reality. So am I.

The idea that I can perceive reality directly – as opposed to building a mental model of it – is usually known as naïve realism. Most of us are naïve realists for most of our lives.

Like my students, naïve realists are very confident in their perception. They don’t doubt what they see. Why would they? They see reality. It’s external and objective.

Naïve realists are also quite confident about any inferences they draw about reality. They base their inferences on concrete, verifiable reality. They start with an assured vision of the world and build outward from there. Conclusions based on concrete reality certainly seem to be realistic.

Naïve realists are often the opposite of what we would call open-minded. They know what they know with little or no doubt. (All of which may contribute to the Dunning-Kruger effect).

But what if you showed naïve realists optical illusions? What if you could show them that their perceptions differ from what other people perceive? What if you could show them illusions that demonstrate that they are creating reality as opposed to perceiving it? If you could, would they become more open minded?

It’s an interesting thought that William Hart and his colleagues recently pursued. The researchers randomly divided students into four different groups. One group completed an intelligence test, another read about chimpanzees, another read about naïve realism, and another read about naïve realism and then viewed a variety of optical illusions. (The original article is here; a less technical summary is here).

The researchers then asked all the students to read stories with ambiguous characters. Their personalities could be interpreted in multiple ways. Those who read about naïve realism and saw the illusions expressed more doubt about their interpretations and were more open to alternative explanations as compared to the other groups. They were more open-minded.

The study suggests that open mindedness may be fundamentally related to our perception of reality. Perhaps the more we learn about the ways we perceive reality, the more open-minded we’ll become. The Internet phenomenon, What color is this dress?, can only help.

So Good, I’m Bad

One leads to the other.

I had a lot of papers to grade last week. It took me longer than I expected but I thought I did a good job of giving insightful advice and feedback. When I finished, I felt a sense of satisfaction and accomplishment. I gave myself a good pat on the back. And then, instead of seizing the moment and doing more wonderful things, … well, I ate a big bowl of ice cream.

I didn’t realize it at the time but I was engaging in moral licensing (also known as moral self-licensing or simply self-licensing). I had done something that I felt good about and, therefore, I could indulge myself in a not-so-good activity. After all, I earned it.

It’s not so bad when I eat a bowl of ice cream. I’m not hurting anyone else. Rather, I’m creating an incentive to stay focused and get the job done. I withhold the reward until the task is complete. That’s not so bad, is it?

But what if it goes farther? As Anna Merritt and her colleagues write, “Past good deeds can liberate individuals to engage in behaviors that are immoral, unethical, or otherwise problematic, behaviors that they would otherwise avoid for fear of feeling or appearing immoral.”

According to Norman Goldfarb, moral licensing works in two ways:

Moral credentials – by doing good deeds, I establish my moral bona fides. I have the credentials that prove (to me, if no one else) that I’m a moral person. A person with such credentials wouldn’t do anything immoral. So, if I do something bad, well… it must be a mistake, not a moral failure.

Moral credits – as Goldfarb puts it, “a person’s good deeds put moral dollars in a moral bank that can be withdrawn later to pay for immoral acts.”

Using credits or credentials, I can do immoral things and still conceive of myself as a moral and upstanding person. So, why not do them?

Much of the literature on moral licensing focuses on “past good deeds” that grant absolution for future not-so-good deeds. But there’s also a future dimension to licensing. I’m going to church tomorrow, so I can take advantage of someone tonight. I’m going on a diet next week, so I can pig out this week. In Goldfarb’s terminology, we can bank moral credits even before they occur. We just have to think about them.

There’s also a judgmental aspect to self-licensing. A fascinating study by Kendall Eskine at Loyola (New Orleans) suggests that eating organic foods makes you more judgmental. Research participants sampled a variety of organic and nonorganic foods. Those who sampled, “… organic foods volunteered significantly less time to help a needy stranger, and they judged moral transgressions significantly harsher than those who viewed nonorganic foods.” Doing good deeds – for ourselves or others – builds our moral credentials and can make us feel superior to those who don’t meet our same high standards. We criticize them more harshly than we otherwise would.

Doing good deeds, then, can lead to a life of immorality and hypocrisy. That’s not what I learned in Boy Scouts. Apparently, however, this is another factory-installed bias. It’s who we are. It’s baked into our DNA.

Like our other biases, the only answer is awareness. We can’t flush this behavior out of our systems. It’s in too deep. But we can be aware of it. We can apply self-awareness to self-licensing. We can take our time and think about our thinking. If we do, then perhaps moral behavior will lead to moral behavior instead of the opposite.

Hedgehogs, Foxes, and The Future

Not Louise.

My friend, Louise, is a world-class forecaster. I’m trying to figure out how she does it.

Louise and I both volunteered for the Good Judgment Project, a crowd-sourced forecasting tournament for world events. Here’s a sample of the questions we’re forecasting:

When will China next conduct naval exercises in the Pacific Ocean beyond the first islands chain?

When will SWIFT next restrict any Russian banks from accessing its services?

When will Ethiopia experience an episode of sustained domestic armed conflict?

For each question, we get 100 points and a calendar. We distribute the 100 points based on when we expect an event to happen. If we don’t expect the event to happen, we simply place all 100 points beyond the calendar.

Philip Tetlock, who wrote the landmark study, Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know?, started the Good Judgment Project to improve forecasting of political events worldwide. Why would we need to improve our forecasting? Because experts are really lousy at it.

In his book, Tetlock studied 28,000 projections made by 284 experts. The results were little better than chance. Computers could do better. Tetlock surmised that crowds might do even better and started the Good Judgment tournament.

The tournament starts anew every year with several hundred volunteers. Louise and I participate in a tournament that started last December. We’ve been forecasting for close to three months. I looked up the standings last week. Louise was number one worldwide. I was number 48.

How does Louise do it? It could be that she’s a fox as opposed to a hedgehog. According to the Greek poet Archilochus, “The fox knows many things but the hedgehog knows one big thing.” Isaiah Berlin popularized the idea in the 1950s with his study of Tolstoy, titled The Hedgehog and The Fox.

So, which is better: a hedgehog or a fox? As with so many things, it depends on what you’re aiming to do. In Good To Great, Jim Collins argues that you need a hedgehog mentality to build a great company. You need to know one big thing and stick to it.

But what if you’re trying to forecast the future? Tetlock argues persuasively that foxes are better than hedgehogs. Why? Here’s how Stewart Brand explains it: “…hedgehogs have one grand theory (Marxist, Libertarian, whatever) which they are happy to extend into many domains, relishing its parsimony, and expressing their views with great confidence. Foxes, on the other hand are skeptical about grand theories, diffident in their forecasts, and ready to adjust their ideas based on actual events.”

It’s probably fair to guess that Louise is a fox. She doesn’t have one grand theory that explains everything from SWIFT financial transactions to Chinese naval maneuvers. She’s also flexible in her thinking. She’s willing to pick ideas from different sources and change her position if the evidence warrants. She gathers feedback and uses it to adapt and adjust.

In Tetlock’s studies, foxes outperform hedgehogs by a wide margin – in forecasting, though perhaps not in building great companies. Hedgehogs on the other hand, “…even fare worse than normal attention-paying dilettantes.”

Louise and I – and other volunteers in the Good Judgment Project – are probably normal attention-paying dilettantes. We follow current events but we don’t have grand theories that explain everything. In some cases, I suspect that Louise doesn’t know what to think. But she does know how to think. Like a fox.

Just Add Women

You doubt my effectiveness?

Germany is poised to join the 30 Percent Club. Beginning in 2016, women must hold at least 30 percent of board seats at large, public companies. Germany will join other countries like Norway, France, Spain and the Netherlands in mandating female representation on boards of directors.

Will it work? It depends on what the goal is. Norway began the trend in 2006, mandating 40% representation. As The Economist puts it, “…[the] law has not been the disaster some predicted.” Not exactly a ringing endorsement but the magazine suggests that the real benefit may be a change in attitude.

The Financial Times appears a bit more optimistic: “Early analysis appears to show that quotas work and have been highly successful across Europe.” Fortune appears less sanguine, “a close look at the results of these quotas – and of Norway’s in particular, which have been in effect the longest – shows that the results might not be all that their backers intend.” Fast Company is more positive.

The articles I’ve cited here seem to have different views of what success means. If success is defined as:

- More female representation on boards, then the quotas work.

- Better financial and stock performance, then the results are decidedly mixed.

- Fewer layoffs, then the quotas seem to work.

Unfortunately, none of the articles discuss why boards with women might perform better. I’ve found two different reasons in the literature that suggest that women can bring important qualitative differences to board discussions and decisions.

First, women appear to make better decisions about risk, especially under stress. The research comes from Mara Mather and Nicole Lighthall who study the effects of stress on decision-making. They found that stress changes the way we select alternatives and accentuates differences between men and women. Bottom line: “…stress amplifies gender differences in strategies during risky decisions, with males taking more risk and females less risk under stress.”

Why would that be? Writing in the New York Times, Therese Huston argues that it may be empathy. We generally view women as more empathetic than men. Under stress, Huston writes, women “… actually found it easier than usual to empathize and take the other person’s perspective. Just the opposite happened for the stressed men — they became more egocentric.”

The second major reason stems from the impact of women on group behavior and effectiveness. MIT reports that the “tendency to cooperate effectively is linked to the number of women in a group.” In The Atlantic, Derek Thompson writes that group intelligence is similar to general intelligence in an individual. General intelligence suggests that an individual who is good at one thing is likely to be good at other things as well. Similarly, a group that’s good at one thing is likely to be good at other things, too. This is dubbed collective intelligence, which varies from group to group.

What factors contribute to collective intelligence? It’s not the average intelligence of the people in the group. Nor is it the intelligence of the smartest person. Thompson notes that we can rule out many other things as well, including motivation, cohesion, and employee satisfaction.

So what makes a group collectively intelligent? Average social sensitivity. It’s the ability to read between the lines and understand what someone is really saying. Thompson writes, “social sensitivity is a kind of literacy, and it turns out that women are naturally more fluent in the language of tone and faces than the other half of their species.”

So women make better decisions in stressful situations. Boards have to deal with high levels of stress. Women also make groups more effective. Boards, of course, are groups of people trying to reach effective decisions. The debate on women on boards was generally framed by the question: Why would we put women on boards? With our new understanding, the proper question is: why wouldn’t we?

(The New York Times also has an interesting on group effectiveness and female participation. Click here.)

What Is Consciousness Good For?

My subconscious is driving the car.

Can you solve a moderately difficult arithmetic problem (say, 3 + 6 – 2 + 5) in your head? Sure, you can. You just need to think about it for a moment.

Could you do the same problem in your head if a researcher were flashing an incredibly annoying bright light in your eye? The light is so bright and flashes so quickly that it’s impossible to focus your attention. Yet, you can still solve the problem. How can that be?

The short answer is that your subconscious (aka System 1 in this website) does the work. It can process arithmetic problems or word puzzles that you’re not consciously aware of.

Professors from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem figured this out with an ingenious experiment. They presented the bright flashing light to one eye and arithmetic or word problems to the other eye. The light was so distracting that subjects didn’t realize that a problem was entering their brain. Yet, they were able to solve it just fine, without realizing that they were doing so. (Here’s the original research article; here’s a less technical summary from the BBC).

The subjects weren’t able to “think about it for a moment”. They couldn’t engage their conscious (System 2) thinking. So, how did they do it? It had to be their subconscious, or System 1.

This finding starts to challenge our long-held beliefs about the differences between our conscious and subconscious processes. We believed that certain skills – like arithmetic and word puzzles – require higher order processing. We need to engage System 2 and focus our attention. But this experiment, and many others like it, demonstrates that System 1 can do a lot more than we expected on its own. (For another example of how your brain can absorb information subconsciously, click here).

Ran Hassin, one of the authors of the flashing light study, went on to create a “Yes It Can” (YIC) model of the subconscious. Hassin asks the simple question, “Which high level cognitive functions can the unconscious perform, and which are uniquely conscious?” After reviewing numerous experiments, he argues, “…that unconscious processes can perform the same fundamental, high-level functions that conscious processes can perform.” (Click here for the article).

Let’s assume for a moment that Hassin is right – our subconscious mind can perform essentially the same functions as our conscious mind. Why, then, do we need consciousness?

Hassin points out that, “Good sprint runners can run 100 meters in less than ten seconds, but more often than not they choose not to.” Similarly, we might be able to use our subconscious for many tasks but – for one reason or another – we choose not to.

When I learned to drive, for instance, I was very conscious of the car itself, the dials on the dashboard, speed, road conditions, and so on. Today, driving is second nature to me. I can drive for miles without being consciously aware of it. It’s often called highway hypnosis.

My subconscious drives the car just fine until something out of the ordinary happens. When something novel (and perhaps dangerous) occurs, I instantly revert to conscious mode. According to Hassin’s argument, my subconscious might be able to handle the novel situation on its own. But, for one reason or another, my conscious mind can handle it better.

Perhaps the main role of consciousness, then, is to practice and master novel skills or to react to novel situations. As our skills improve, our subconscious takes over much of the task. Our conscious mind can move on to new things.

Perhaps our conscious mind continually hungers for novelty. We get bored when there is nothing new for our consciousness to work on. This could even explain the hedonic treadmill. New things engage us and make us happy. Old things fade into the (subconscious) wallpaper.

Consciousness, then, may be a fundamental force driving us toward creativity and innovation. Seen in this light, creativity is not simply a “good thing.” Rather it’s a “necessary thing.” We should pay more attention.