Librarian, Farmer, Debacle

In his book, Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman has an interesting example of a heuristic bias. Read the description, then answer the question.

Steve is very shy and withdrawn, invariably helpful but with little interest in people or in the world of reality. A meek and tidy soul, he has a need for order and structure, and a passion for detail.

Is Steve more likely to be a librarian or a farmer?

I used this example in my critical thinking class the other night. About two-thirds of the students guessed that Steve is a librarian; one-third said he’s a farmer. As we debated Steve’s profession, the class focused exclusively on the information in the simple description.

Kahneman’s example illustrates two problems with the rules of thumb (heuristics) that are often associated with our System 1 thinking. The first is simply stereotyping. The description fits our widely held stereotype of male librarians. It’s easy to conclude that Steve fits the stereotype. Therefore, he must be a librarian.

The second problem is more subtle — what evidence do we use to draw a conclusion? In the class, no one asked for additional information. (This is partially because I encouraged them to reach a decision quickly. They did what their teacher asked them to do. Not always a good idea.) Rather they used the information that was available. This is often known as the availability bias — we make a decision based on the information that’s readily available to us. As it happens, male farmers in the United States outnumber male librarians by a ratio of about 20 to 1. If my students had asked about this, they might have concluded that Steve is probably a farmer — statistically at least.

The availability bias can get you into big trouble in business. To illustrate, I’ll draw on an example (somewhat paraphrased) from Paul Nutt’s book, Why Decisions Fail.

Peca Products is locked in a fierce competitive battle with its archrival, Frangro Enterprises. Peca has lost 4% market share over the past three quarters. Frangro has added 4% in the same period. A board member at Peca — a seasoned and respected business veteran — grows alarmed and concludes that Peca has a quality problem. She sends memos to the executive team saying, “We have to solve our quality problem and we have to do it now!” The executive team starts chasing down the quality issues.

The Peca Products executive team is falling into the availability trap. Because someone who is known to be smart and savvy and experienced says the company has a quality problem, the executives believe that the company has a quality problem. But what if it’s a customer service problem? Or a logistics problem? Peca’s executives may well be solving exactly the wrong problem. No one stopped to ask for additional information. Rather, they relied on the available information. After all, it came from a trusted source.

So, what to do? The first thing to remember in making any significant decision is to ask questions. It’s not enough to ask questions about the information you have. You also need to seek out additional information. Questioning also allows you to challenge a superior in a politically acceptable manner. Rather than saying “you’re wrong!” (and maybe getting fired), you can ask, “Why do you think that? What leads you to believe that we have a quality problem?” Proverbs says that “a gentle answer turneth away wrath”. So does an insightful question.

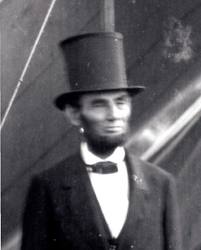

Little Life Lessons from Lincoln

On July 4, 1863, Robert E. Lee was leading a Confederate army in retreat from Gettysburg when they were trapped against the rain-swollen Potomac River. The Union army, commanded by General George Meade, pursued the rebels. Abraham Lincoln ordered Meade to attack immediately. Instead, Meade dithered, the weather cleared, the river shrank, and Lee and his army escaped. Lincoln was furious and penned this letter to Meade:

I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee’s escape. He was within our easy grasp, and to have closed upon him would, in connection with our other late successes, have ended the war. As it is, the war will be prolonged indefinitely. If you could not safely attack Lee last Monday, how can you possibly do so south of the river, when you can take with you very few— no more than two-thirds of the force you then had in hand? It would be unreasonable to expect and I do not expect that you can now effect much. Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasurably because of it.

Interestingly, Lincoln never sent the letter — it was found among his papers after his death. Lincoln generally praised his colleagues for their positive accomplishments and said little or nothing about their failures. Apparently, he wrote letters like the one to Meade to relieve his own frustrations — and perhaps to leave a record for history — rather than to humiliate his colleagues and create public acrimony.

As Douglas Wilson, a Lincoln scholar, pointed out in a recent article (click here), Lincoln was great communicator but not necessarily in the way we think. Some tidbits on how he worked:

- He rarely spoke in public and when he did he was very well prepared. We think of the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural speech as great feats of oratory — and they were. But there weren’t many such feats; he gave relatively few speeches. And he almost never spoke off the cuff. He knew that people followed his words closely and he prepared meticulously. His speeches were extraordinary. Equally extraordinary is the fact that he almost never said anything stupid that he had to retract. Our politicians and executives today could learn a lot from him.

- He pre-wrote his speeches. Lincoln always had scraps of paper with him — which he often stored in his hat. When an idea — or an elegant way to phrase an idea — came to him, he jotted it down. He didn’t start thinking about his speeches when a deadline drew near. He was thinking about them virtually all the time.

- He was mercifully brief. The Gettysburg Address consisted of 267 words. By contrast, this post has about 600. Which one do you think will live longer?

- He cultivated the press before he needed them. In general, Lincoln got to know his audience before he spoke to them. He gave favors to journalists before he asked for favors in return. Getting to know your audience and letting them know that you genuinely care about them are always good strategies.

- He understood event jujitsu. The Civil War began with the crisis at Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor. Lincoln could have sent in a fleet to shoot up the Confederate fortifications. Instead, he sent in a small re-supply mission. When the Confederates sought to block the mission, they fired the first shots of the war. It’s a small leap to conclude that the Confederates “started” the war. Thus, a small incident became a major victory in the battle to shape perceptions.

Lincoln has always been one of my favorite presidents and I certainly enjoyed the recent movie from Steven Spielberg. Lincoln communicated effectively and was an expert at shaping public opinion. As the movie showed, he was also adept at cutting deals and rolling logs to achieve his greater goals. Not bad for a kid from the prairies.

Thinking With Your Body

When I’m happy, I smile. A few years ago, I discovered that the reverse is also true: when I smile, I get happy. I’ve also found that standing up straight — as opposed to slouching — can improve my mood and perhaps even my productivity.

It turns out that I was on to something much bigger than I realized at the time. There’s increasing evidence that we think with our bodies as well as our minds. Some of the evidence is simply the way we express our thoughts through physical metaphors. For instance, “I’m in over my head”, “I’m up to my neck in trouble”, “He’s my right hand man”, and so on. Because we use bodily metaphors to express our mental condition, the field of “body thinking” is often referred to a metaphor theory. Perhaps more generally, it’s called embodied cognition.

In experiments reported in New Scientist and in Scientific American, we can see some interesting effects. For instance, with people from western cultures, “up” and “right” mean bigger or better while “down” or “left” mean smaller or worse. So, for instance, when volunteers were asked to call out random numbers to the beat of a metronome, their eyes moved upward when the next number was larger and moved downward when the next number was smaller. Similarly, volunteers were asked to gauge the number of objects in a container. When they were asked to lean to the left while formulating their estimate, they guessed smaller numbers on average. When leaning to the right, they guessed larger numbers.

In another experiment, volunteers were asked to move boxes either: 1) from a lower shelf to a higher shelf; or 2) from a higher shelf to a lower shelf. While moving the boxes, they were asked a simple, open-ended question, like: What were you doing yesterday? Those who were moving the boxes upward were more likely to report positive experiences. Those who were moving the boxes downward were more likely to report negative experiences.

When I speak of the future, I often gesture forward — the future is ahead of us. When I speak of the past, I often do the opposite, gesturing back over my shoulder. Interestingly, the Aymara Indians of highlands Bolivia are reported to do the opposite — pointing backward to the future and forward to the past. That seems counter-intuitive to me but the Aymara explain that the future is invisible. You can’t see it. It’s as if it’s behind you where it can quite literally sneak up on you. The past, on the other hand, is entirely visible — it’s spread out in front of you. That makes a lot of sense but my cultural training is so deeply embedded that I find it very hard to point backward to the future. It’s an interesting example of cultural differences influencing embodied cognition.

Where does this leave us? Well, it’s certainly a step away from Descartes’ formulation of the mind-body duality. The body is not simply a sensing instrument that feeds data to the mind. It also feed thoughts and influences our moods in subtle ways. Yet another reason to take good care of your body.

The Last of Thumb Thinking

Sure it’s dangerous. But we’re in control. No problem!

Heuristics are simply rules of thumb. They help us make decisions quickly and, in most cases, accurately. They help guide us through the day. Most often, we’re not even aware that we’re making decisions. Unfortunately, some of those decisions can go haywire — precisely because we’re operating on automatic pilot. In fact, psychologists suggest that we commonly make 17 errors via heuristics. I’ve surveyed 11 of them in previous posts (click here, here, and here). Let’s look at the last six today.

Optimistic bias — can get us into a lot of trouble. It leads us to conclude that we have much more control over dangerous situations than we actually do. We underestimate our risks. This can help us when we’re starting a new company; if we knew the real odds, we might never try. It can hurt us, however, when we’re trying to estimate the danger of cliff diving.

Hindsight bias — can also get us into trouble. Everything we did that was successful is by dint of our own hard work, talent, and skill. Everything we did that was unsuccessful was because of bad luck or someone else’s failures. Overconfidence, anyone?

Elimination by aspect — you’re considering multiple options and drop one of them because of a single issue. Often called, the “one-strike-and-you’re-out” heuristic. I think of it as the opposite of satsificing. With satsificing, you jump on the first solution that comes along. With elimination by aspect, you drop an option at the first sign of a problem. Either way, you’re making decisions too quickly.

Anchoring with adjustment — I call this the “first-impressions-never-die” heuristic and I worry about it when I’m grading papers. Let’s say I give Harry a C on his first paper. That becomes an anchor point. When his second paper arrives, I run the risk of simply adjusting upward or downward from the anchor point. If the second paper is outstanding, I might just conclude that it’s a fluke. But it’s equally logical to assume that the first paper was a fluke while the second paper is more typical of Harry’s work. Time to weigh anchor.

Stereotyping — we all know this one: to judge an entire group based on a single instance. I got in an accident and a student from the University of Denver went out of her way to help me out. Therefore, all University of Denver students must be altruistic and helpful. Or the flip side: I had a bad experience with Delta Airlines, therefore, I’ll never fly Delta again. It seems to me that we make more negative stereotyping mistakes than positive ones.

All or Nothing — the risk of something happening is fairly low. In fact, it’s so low that we don’t have to account for it in our planning. It’s probably not going to happen. We don’t need to prepare for that eventuality. When I cross the street, there’s a very low probability that I’ll get hit by a car. So why bother to look both ways?

As with my other posts on heuristics and systematics biases, I relied heavily on Peter Facione’s book, Think Critically, to prepare this post. You can find it here.

The Anatomy of Debacles

I was satisficing. If only I had known.

What’s a debacle? According to Paul Nutt, it’s “…merely a botched decision that attracts attention and gets a public airing.” Nutt goes on to write that his “…research shows that half of the decisions made in business and related organizations fail.” Actually, it may be higher because, “failed decisions that avoid a public airing are apt to be covered up.”

Remember that I wrote not long ago (click here) that perhaps 70% of change management efforts fail? Now we learn that half — or more — of all business decisions fail. We’re not doing so well. Nutt has studied over 400 debacles — botched decisions that became public disasters — and has created an anatomy of why and how they happen. Nutt’s book, Why Decisions Fail, is a sobering look at how we manage our organizations and, more specifically, our decisions.

Critical thinking should help us avoid botched decisions and public debacles. I’ll be writing about critical thinking over the next several months and, from time to time, will pull ideas from Nutt’s book. Today, let’s set the stage by looking at the basics. Nutt writes that blunders happen because of three broad reasons:

- Failure-prone practices — Nutt claims that two-thirds of business decisions are arrived at via common practices that are known to fail. One of our problems is that we typically don’t analyze the decision-making process itself. We tend to ask, “how can we correct the problem?” rather than “how did our decision-making process lead us astray?” As an example, Nutt notes that “Nearly everyone knows that participation prompts acceptance, but participation is rarely used.”

- Premature commitments — Nutt writes that “Decision makers often jump at the first idea that comes along and then spend years trying to make it work.” In the vocabulary of critical thinking, this is known as satisficing or temporizing — two heuristics that can lead us astray. Nutt concludes that, “A rush to judgment is seductive and deadly and can be headed off.” I’ll write more on how to head it off in future articles.

- Wrong-headed investments — the basic problem here is that we spends lots of time, energy, and money to demonstrate that our decision is correct and the ideas behind it are sound. We call it an evaluation but really, it’s a justification. It’s better to invest our energy in clarifying objectives, discovering issues (and opportunities), and identifying measures of risk and benefit.

Nutt also criticizes contingency theory — the idea that your situation dictates your tactics. For instance, if you’re faced with a community boycott, you should do X; if you’re faced with cost overruns, you should do Y. Nutt concludes that, “Best practices can be followed regardless of the decision to be made or the circumstances surrounding it.” The bulk of his book outlines what those best practices are.

Of course, there’s a lot more to it. I’ll outline the highlights in future posts and put Nutt’s findings in the general context of critical thinking. I hope you’ll follow along. In the meantime, don’t make any premature commitments.