Stemming the STEM Tide

Can we make science fun?

I sometimes get a bit depressed when reading about scholastic achievement in America. For instance, in the 2012 edition of the PISA tests (Program for International Student Achievement) American teenagers ranked as average or below average in math, science, and reading. (The test measures achievement for 15-year-olds).

The Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a group of 34 mostly first-world countries, administers PISA every three years. In addition to the member states, other countries can also request to take the tests. In 2012, 65 countries participated. Compared to the 65 countries, the USA ranked

- 30th in math;

- 23rd in science, and;

- 20th in reading.

Since OECD first administered the tests in 2000, American performance has not changed much. Our relative position, however, has fallen as other countries have passed us by. Arne Duncan, our Secretary of Education, says that the results “must serve as a wake-up call” for the nation. (Here’s a good infographic on the results. Here’s an in-depth report from OECD.)

But is it really a crisis? Sure, it would be great to be number one in everything, but if we had to choose, would it be better to be first in teen achievement or in national achievement? According to the Bloomberg Innovation Quotient, for instance, America is the most innovative country in the world. The Global Innovation Index is a little less sanguine, but still ranks the USA as the fifth most innovative nation in the world.

It appears, then, that poor adolescent performance doesn’t lead directly to poorer national performance. Though our 15-year-olds are average (at best) perhaps our 21-year-olds are not. Perhaps our colleges and universities are picking up the slack. Perhaps innovation stems from creativity more than mastery of science, math, and reading. Perhaps our national diversity creates opportunities that are not found in more homogeneous countries. Perhaps … well, there are so many variables that it’s hard to sort them out.

In a related field, we’ve seen a lot of handwringing about STEM in America. STEM includes all disciplines in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math. Over the past several decades, critics have suggested that we’re recruiting too few students into STEM fields and that too many are dropping out. As with the PISA scores, analysts suggest that a crisis is brewing and must be fixed or we’ll inexorably decline as a nation.

Really? A recent article in Science magazine points out that “…new data poke major holes in the conventional wisdom.” For instance, conventional wisdom holds that the attrition rate for STEM students is very high. Indeed, as many as 50% of STEM students drop out or switch to non-STEM majors. That does sound high but nobody had researched the attrition rate in other disciplines. When researchers actually looked at other fields, they found the attrition rate in the humanities was 56% and in business was 50%. In other words, students really aren’t very good at deciding what to major in when they first arrive at university.

Conventional wisdom also holds that very few students transfer to STEM majors. STEM is characterized by “low inflow and high outflow”. But a study from Indiana University suggests otherwise. Of students who entered college expecting to major in a STEM field, 24% changed to a non-STEM field by the end of their first year. That sounds like a lot but the study also found that 27% of students who entered college in a non-STEM field had transferred to a STEM curriculum in their first year. As the Science article concludes, it’s a two-way street.

What does all this mean? I think it’s time to put on our critical thinking caps, step back, take a deep breath, and define the problem more clearly. I’m not arguing that there’s no problem. But I do believe that we’ve defined the problem incorrectly.

Chris Christie: The I Guy

Me, myself, and I

In my video, Five Tips for the Job Interview, my first tip is to be careful how often you say “I” as opposed to “we”. If the company you’re interviewing with is looking for team players — and many companies say they are — then saying “I” too often can hurt your chances. You can come across as self-centered and egocentric. Someone, in other words, who doesn’t play well with others.

I thought about this tip the other day when I watched Chris Chrstie’s press conference addressing the bridge closure scandal. (If you haven’t heard about it, you can get a good summary here). As the Republican governor of a very Democratic New Jersey, Chritsie is widely regarded as an appealing candidate for the Republican nomination for president in 2016. In a way, he’s interviewing for the biggest job of all. Perhaps he should have watched my video.

In the press conference, Christie needed to address a scandal that appears to be about naked political payback. The Democratic mayor of Fort Lee, New Jersey didn’t endorse Christie for governor in the recent campaign. As a result (it appears), Christie’s minions shut down traffic in Fort Lee for four days. Christie needed to apologize and distance himself from such nasty political deeds.

Dana Milbank, a columnist for the Washington Post, paid close attention to the press conference. In fact, he went through the transcript and analyzed Christie’s language. The press conference lasted 108 minutes; Christie said some form of “I” or “me” (I, I’m, I’ve, me, myself) 692 times. That’s 6.4 times per minute or a little more than once every ten seconds.

The net result is that Christie comes across as an egomaniac. That may be the case but, generally, you don’t want to come across that way in an important interview. There’s a lot that I like about Governor Christie — he seems to be one of the few politicians in America who can actually pronounce the word “bipartisan”. I hope he can learn to pronounce “we” and “you” as well.

Good News on Dementia?

Harriet speaks to the future.

My mother-in-law, Harriet, is a delightful nonagenarian who is still as sharp as a tack. What’s the secret to her mental acuity? I’m willing to bet that the fact that she’s an avid bridge player has something to do with it.

Indeed, Harriet may be a leading indicator of the changing shape of the dementia demographic. Conventional wisdom holds that our health care system is about to be overwhelmed as the baby boom ages and sinks into dementia.

The logic is straightforward. Major premise: Old age is the leading risk factor for dementia. Minor premise: People are living longer. Conclusion: Everybody will become demented sooner or later and our health care system will collapse.

In the current issue of New Scientist, however, Liam Drew reports on new research that suggests that Harriet may be an emblem of change, not an exception to it. As Drew points out, the conventional wisdom “… is based on the assumption that people will continue to develop dementia at the same rate as they always have.” Drew then reports on two studies that suggest this assumption is no longer true (if it ever was).

The first is a research report from the Lancet that compares two dementia censuses conducted 20 years apart in three regions the U.K. The first census, conducted in 1994, counted 650,000 people with dementia. In 2013, the researchers repeated the study and, assuming that the dementia rate held steady, projected that they would find 900,000 people with dementia. Instead, they found about 700,000. The report concludes that, “Later-born populations have a lower risk of prevalent dementia than those born earlier in the past century.”

The second study, conducted in Denmark, reached essentially the same conclusion. The research compared people born in 1905 with those born in 1915. Drew reports that, “While the two groups had similar physical health, those born in 1915 markedly outperformed the earlier-born in cognitive tests.”

So, what’s going on? Well, for one thing, we’re taking better care of our hearts. In general, healthier hearts provide better circulation. More oxygen-rich blood reaches our brains, which probably improves brain health. A heart healthy lifestyle may also be a brain healthy lifestyle.

Another theory is cognitive reserve, which suggests that we may be able to make our brains more resilient and resistant to damage. In other words, the brain is not just a “given”; it can be developed in much the same way that a muscle can. As Wikipedia puts it, “Exposure to an enriched environment, defined as a combination of more opportunities for physical activity, learning and social interaction, may produce structural and functional changes in the brain and influence the rate of neurogenesis … many of these changes can be affected merely by introducing a physical exercise regimen rather than requiring cognitive activity per se.”

What creates cognitive reserve? Educational attainment seems to play an important role. Physical and social activity also seem to contribute. I can’t help but wonder whether playing bridge – which combines social and cognitive elements – might not be the perfect way to build our cognitive reserves.

Over the years, we’ve all learned a lot from Harriet. She’s smart and she’s wise. And she may just have taught us how to live intellectually rich lives for many years to come. Thank you, Harriet.

Groups Get It Wrong (All Too Often)

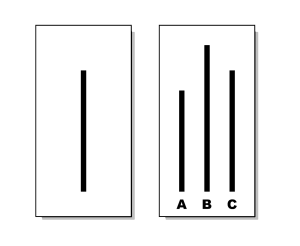

The right answer is obviously B.

Why do decisions go wrong? Many times, it’s because the decision is made by a group, not by an individual. Individuals tend to look at the evidence and make a decision. It may not be the right decision but it’s often based on an assessment of the facts.

Groups may assess the facts as well but they also assess the politics of the situation. The issue may be decided on group dynamics rather than a dispassionate review of the evidence.

Bain & Company recently published a white paper (Decision Insights: How Group Dynamics Affect Decisions) that provides a useful summary of the issues. Here are four ways, for instance, that group dynamics can lead to debacles.

Conformity – if you’re a team player, you may go with the team’s decision even if you realize it’s wrong. The graphic above shows Solomon Asch’s classic experiment. Which line – A, B, or C – is the same length as the line to the left? Working alone, you’ll probably figure out that C is the right answer. However, if you’re in a group that says B is the right answer, you’re quite likely to go with the group. Many companies say they want team players, but they need to be aware of the implications. (See also Group Behavior – The Risky Shift.)

Group Polarization – let’s assume for a moment that you belong to a politically conservative group. You talk to conservatives regularly. Indeed, you talk only to conservatives. You reinforce each other and the group gets more and more conservative. In many cases, the group becomes more conservative than any of its individual members. (See also, Will The Internet Cause Dementia? and Where You Stand Depends on Where You Sit.)

Obedience to Authority – the quickest way to stifle innovation is to let the boss speak first. We all want to please our bosses, so if the boss expresses a preference for X over Y, we often begin to find reasons why X is indeed better than Y. It’s hard to argue with your boss … unless you’re specifically asked to play the role of devil’s advocate, which is often a good idea. Note to bosses: keep quiet. (See also, Want A Good Decision? Go To Trial.)

Bystander Effect – when we’re not sure what to do, we often look to others to see what they’re doing. If they’re panicking, we get panicky. If they’re cool, calm, and collected, we calm down (even if we think we should panic). Individuals often understand a situation better than groups do which is why you should never have a heart attack in a crowd.

So, what to do? Diversity in a group often helps overcome groupthink and polarization, so pull people together from different backgrounds and risk profiles. Playing roles can help. You might stage a mock trial or ask someone to play the devil’s advocate. You can also ask each individual to write down his or her recommendation anonymously, put them all in a hat, and then discuss all of them. You can also prime the team by discussing what it means to be a team player. Emphasize the need to make the best decision, not just the most comfortable one.

And, if all else fails, just ask the boss to leave the room.

Seeing And Observing Sherlock

Pardon me while I unitask.

I’m reading a delightful book by Maria Konnikova, titled Mastermind: How To Think Like Sherlock Holmes. It covers much of the same territory as other books I’ve read on thinking, deducing, and questioning but it reads more like … well, like a detective novel. In other words, it’s fun.

In the past, I’ve covered Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast and Slow. Kahneman argues that we have two thinking systems. System 1 is fast and automatic and always on. We make millions of decisions each day but don’t think about the vast majority of them; System 1 handles them. System 1 is right most of the time but not always. It uses rules of thumb and makes common errors (which I’ve cataloged here, here, here, and here).

System 1 can also invoke System 2 – the system we think of when we think of thinking. System 2 is where we logically process data, make deductions, and reach conclusions. It’s very energy intensive. Thinking is tiring, which is why we often try to avoid it. Better to let System 1 handle it without much conscious thought.

Kahneman illustrates the differences between System 1 and System 2. Konnikova covers some of the same territory but with slightly different terminology. Konnikova renames System 1 as System Watson and System 2 as System Holmes. Konnikova proceeds to analyze System Holmes and reveal what makes it so effective.

Though I’m only a quarter of the way through the book, I’ve already gleaned a few interesting tidbits, such as these:

Motivation counts – motivated thinkers are more likely to invoke System Holmes. Less motivated thinkers are willing to let System Watson carry the day. Konnikova points out that thinking is hard work. (Kahneman makes the same point repeatedly). Motivation helps you tackle the work.

Unitasking trumps multitasking – Thinking is hard work. Thinking about multiple things simultaneously is extremely hard work. Indeed, it’s virtually impossible. Konnikova notes that Holmes is very good at one essential skill: sitting still. (Pascal once remarked that, “All of man’s problems stem from his inability to sit still in a room.” Holmes seems to have solved that problem).

Your brain attic needs a spring cleaning – we all have lots of stuff in our brain attics and – like the attics in our houses – a lot of it is not worth keeping. Holmes keeps only what he needs to do the job that motivates him.

Observing is different than seeing – Watson sees. Holmes observes. Exactly how he observes is a complex process that I’ll report on in future posts.

Don’t worry. I’m on the case.