Curmudgeons and Critical Thinking

My brain thinks it so it must be true.

I don’t consider myself a curmudgeon. But every now and then my System 1 takes off on a rant that is entirely irrational. It’s also subconscious so I don’t even know it’s happening.

My System 1 wants to create a continuous story of how I interact with the world. Sometimes the story unfolds rationally. I use solid evidence to create a story that flows logically from premise to conclusion.

Sometimes, however, there’s no solid evidence available. Does that stop my System 1 from concocting a story? Of course not. I simply make up a story out of whole cloth. The story may well be consistent in its internal details but may also be entirely fictional. I use it to satisfy my need for a comforting explanation of the world around me. In this regard, it’s no different from a child’s bedtime story.

Though I refer to it as System 1, it’s actually my left brain interpreter that does the work. According to Wikipedia, “…the left brain interpreter refers to the construction of explanations by the left brain in order to make sense of the world by reconciling new information with what was known before. … In reconciling the past and the present, the left brain interpreter may confer a sense of comfort to a person, by providing a feeling of consistency and continuity in the world. This may in turn produce feelings of security that the person knows how “things will turn out” in the future.”

Apparently, our desire for “feelings of security” is deep and strong. So strong, in fact, that our left brain interpreter may create a “contrived” story even in the absence of facts, data, and evidence. While the interpreter often interprets things logically, it “…may also enhance the opinion of a person about themselves and produce strong biases which prevent the person from seeing themselves in the light of reality.”

How often does the interpreter create completely contrived stories? More often than you might think. In fact, my left brain interpreter took off on a flight of fancy just the other day.

Suellen and I were driving to an event at the University of Denver. We were running a few minutes late. We were on a four-lane boulevard where the speed limit is 30 miles per hour. But most people drive at 40 mph because the road is broad and straight. We got stuck behind a Prius that was driving at precisely the speed limit. Here’s how my left brain interpreted the event:

Damn tree-hugger in a Prius! Thinks he’s superior to the rest of us because he’s saving the planet. He wants to keep the rest of us in line too, so he’s driving the speed limit to make sure that we behave ourselves. What a jerk! Who does he think he is? Doesn’t he know it’s rush hour? What gives him the right to drive slowly?

That’s a pretty good rant. But it has nothing to do with reality. I didn’t know anything about the driver but I still created a story to connect the dots. The story followed a simple arc: he’s a jerk and I’m an innocent victim. It’s simple. It’s internally consistent. It enhances my opinion about myself. And it’s completely fictional.

How did I know that I was ranting? Because I interrupted my own train of thought. When I thought about my thinking – and brought the story into my conscious mind – I realized it was ridiculous. It wasn’t his fault that I was running late. And who, after all, was trying to break the law? Not him but me.

I was certainly thinking like a curmudgeon. I suspect that we all do from time to time. I stopped being a curmudgeon only when I realized that I needed to think about my thinking. Curmudgeons may well think primarily with their left brain interpreter. Whatever story the interpreter concocts becomes their version of reality. They don’t think about their thinking.

When we’re with someone who is lost in thought, we might say, “A penny for your thoughts.” It’s a useful phrase that often starts a meaningful conversation. We might make it more useful by altering the wording. To avoid being a curmudgeon, we need to think about our thinking. Perhaps we should simply say, “A penny for my thoughts.”

Rabies and Burglaries

Architect or burglar?

Long-time readers of this column know that I’m an advocate of mashup thinking. You take an idea from Column A and an idea from Column B and mash them together. So, for instance, X-rays (Column A) when mashed up with computerized image processing (Column B), yield an important new product called CT scanners.

A good way to brainstorm is simply to mash up ideas from different categories. You’re not thinking out of the box. Rather you’re thinking out of multiple boxes. What would you get if you mashed up, say paper with pasta? Would it be edible paper? Or maybe pasta that you could print messages on? Would it be useful? Maybe. Maybe not. What’s useful is the process of getting there.

So, I was delighted to see that the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Denver has started a program called Mixed Taste. MCA describes the program as Tag Team Lectures On Unrelated Topics. The idea is simple – they choose two topics (seemingly out of thin air) that are completely unrelated. Then they get speakers to speak on each topic. They rent an auditorium, get a band, invite the public, and have at it.

Last night, the topics were rabies and burglary. I thought of these as two completely unrelated topics but, when you mash them up, you get some surprises. And that’s the point.

At the event, Monica Murphy and Bill Wasik spoke first. They’re good Brooklynites and also the authors of Rabid: A Cultural History of the World’s Most Diabolical Virus. Here are some things you might not know about rabies.

- It doesn’t travel through the blood but through the nervous system. So it outflanks the blood-brain barrier and heads for the brain.

- It “wants” to get to your brain so it can change your behavior. Most importantly, it wants to stop you from drinking water, an activity that would weaken the virus. Thus, rabies victims develop hydrophobia, an extreme reluctance to drink water. (Here’s another virus that changes your behavior).

- It’s been with us for a long time and it’s almost always fatal.

Geoff Manaugh, an architect who created the popular BLDG|BLOG, spoke next. Manaugh also has a book that will launch next spring called, A Burglar’s Guide To The City. Manaugh pointed out that architects are enablers of burglars. Burglars couldn’t operate without built environments. Architects may think they’re building useful or inspiring structures but they’re also creating a playground for burglars. A good burglar can identify patterns in buildings and use them to locate vulnerabilities. Burglars are often avid students of architectural codes.

So what’s the similarity here? The one I took away is this: Burglars are to buildings as rabies is to humans. Here are some similarities:

- Both take structures (buildings, the human body) developed for one purpose and twist them to their own ends.

- Both have evolved the ability to avoid or overcome sophisticated security measures.

- Both spread in similar ways. A rabid animal creates additional rabid animals. A burglar creates additional burglars.

- Both evolve and adapt to changing situations.

I never would have thought of these similarities if MCA hadn’t mashed them up for me. I found it fascinating. But is any of it practical or useful? I’m not sure … but perhaps we can adapt the techniques we use to control viruses to also control burglars (or vice-versa). But even if that’s not the outcome, we’re practicing the art of mashups — an intriguing thinking process that can produce surprising insights and innovations. For that, I thank the MCA.

(By the way, Monica Murphy, Bill Wasik, and Geoff Manaugh are all very good speakers and I recommend them highly to you).

Critical Thinking, Framing, and Red Wine

What else should I have?

I like wine, especially red wine. My tastes range from elegant to earthy. In fact, I’m not terribly discriminating – I like to sample them all.

I also feel the need to justify my red wine indulgences. So I’m always looking for news about the positive health effects of drinking red wine. (This is a classic case of System 2 rationalizing a decision that was initially made – for entirely different reasons — in System 1. My System 1 made the decision; my System 2 justifies it.)

As you may know, there’s plenty of good news about red wine and good health. Generally, drinking red wine is associated with better health and longer life. It’s a J-shaped curve, “…light to moderate drinkers have less risk than abstainers, and heavy drinkers are at the highest risk.” Drink a little bit and you get healthier; drink too much and you get unhealthier.

Is there a cause-and-effect relationship here? It certainly hasn’t been proven. All we’ve been able to show so far is that there is a correlation. A change in one variable is correlated to a change in another variable. Just because variable A happens before variable B, doesn’t mean that A causes B. (That would be the post hoc, ergo propter hoc fallacy as the President points out in West Wing).

Yet many scientists have assumed that there is a cause-and-effect relationship and framed their studies accordingly. The typical approach is to break down the various elements of red wine to isolate the ingredient(s) that cause the beneficial health results. Is it ethanol? Is it resveratrol? Notice the assumption: there is something in the wine that causes the beneficial health result. The studies are narrowly framed.

Is this good critical thinking? Maybe not. Maybe we’re framing too tightly and assuming too much. Maybe there’s a third variable that causes us to drink red wine and be healthier.

I started thinking about this when I stumbled across a study conducted in Denmark more than a decade ago. The Danish researchers didn’t study wine. Rather, they looked at human behavior. More specifically, they looked at 3.5 million grocery store receipts.

The Danish researchers asked three interrelated questions: 1) What do wine drinkers eat? 2) Is this different from what non-wine-drinkers eat? 3) If so, could the differences in overall diet be the cause of the health effect?

The researchers looked at several specific combinations:

- What else did people who bought wine – but not beer – buy at the grocery store? (This group comprised 5.8% of the 3.5 million receipts)

- What else did people who bought beer – but not wine – buy at the grocery store? (6.6% of the total receipts).

- What else did people who bought both beer and wine buy at the grocery store? (1.2% of the total receipts).

I won’t try to summarize everything but here’s the key finding:

“This study indicates that people who buy (and presumably drink) wine purchase a greater number of healthy food items than those who buy beer. Wine buyers bought more olives, fruit or vegetables, poultry, cooking oil, and low fat products than people who bought beer. Beer buyers bought more ready cooked dishes, sugar, cold cuts, chips, pork, butter, sausages, lamb, and soft drinks than people who bought wine. Wine buyers were more likely to buy Mediterranean food items, whereas beer buyers tended to buy traditional food items.”

So, does wine cause good health? Maybe not. Maybe we framed the question improperly. Maybe we’ve been studying the wrong thing. Maybe it’s the other things that wine drinkers do that improve our health. As usual, more studies are needed. While I wait for the results, I think I’ll have a nice glass of Priorat.

Equal Opportunity Idea Generation

Pick a card.

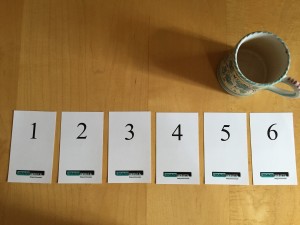

At the beginning of each term, I give my critical thinking students a set of six cards. Each card has a number on it – one through six. (I also add my logo to do a little low-cost branding).

Students bring the cards to each class. I use them to guide discussions about topics where there is no obvious right answer. I ask a question with up to six alternative answers. I then ask the students to select the “best” answers and — when I give a signal – to hold up the number that represents their choice.

The trick is to do it simultaneously. Then I say something like, “Jamal, you’re holding up number six and Carmen is holding up number three. Let’s discuss why you’ve chosen different answers.” This often leads to some very robust discussions. Nobody hides and everyone knows that they may be asked to explain their opinion. If you mix in a little humor, it can also be a lot of fun.

I call these equal opportunity discussions. In most discussions, I find that whoever speaks first exerts undue influence on every subsequent speaker. It’s a phenomenon called social convergence and it’s impossible to eliminate unless you have everyone “speak” simultaneously. With simultaneous responses, everyone has an equal opportunity to get their idea across.

I first used this system during the merger of Lawson, an American software company, and Intentia, a Swedish software company. Both companies had about 2,000 employees. They also had different national traditions and corporate cultures. Every employee had an opinion about what the new company culture should be. The question for managers (including me) was: how do we gather, weigh, and merge these opinions?

We decided to use equal opportunity discussions focused on how the new culture would respond to different behaviors. For instance, in a meeting with up to a dozen employees, we might ask a simple question: “Klaus is always late to staff meetings. In our new company culture, what do you think Klaus’ manager should do?” We included a list of up to six answers. We asked the employees to consider the answers and then hold up her or his chosen answer simultaneously. This produced some very spirited discussions.

We kept track of how different groups answered each question. Did marketers answer the questions differently than, say, engineers? How about executives versus individual contributors? It took time but it was very valuable information that ultimately led to a coherent new culture.

A similar technique works well in promoting innovation. The first step is to gather a wide range of diverse ideas. Letting one person speak first (especially the boss) will reduce diversity. When I ran staff meetings focused on creating new ideas, I would frame up the issues several days in advance. I asked each participant to consider the issue and develop his or her best ideas. I then asked them to write down their ideas – no more than a paragraph or two. When we got to the meeting, I asked everyone to push their written descriptions to the middle of the table. I then gathered them up, shuffled them a bit, and started the discussion.

I thought about these processes when I spotted a recent article in Harvard Business Review titled, “People Offer Better Ideas When They Can’t See What Others Suggest.” The context is slightly different – the authors are looking at programs like Dell’s Idea Storm site or the My Starbucks Idea site.

Though the context is different, the process is essentially the same. The authors write that, “The trick is to avoid clustering, where the same people have the same experiences.” They also created anti-clustering software that ensures “…that no participants share the same body of ideas and the same neighbors as anyone else.”

I’m sure the anti-clustering software is more sophisticated than my cards. But if you want to get off to a quick start, the cards work pretty well. Just make sure that every idea has an equal opportunity to “win”.

Innovation and Bananas

Start from the top.

We’ve all heard the admonition, “If it ain’t broke don’t fix it.” We often take it at face value – if something is working, don’t make changes. On the other hand, we usually roll our eyes when a colleague justifies a process by saying, “Well, we’ve always done it that way.”

So which is it? Should you accept a process simply because it’s traditional? Should you assume that it doesn’t need attention? If your business processes are working reasonably well, should you never review them? Should you never seek to improve a process that’s fulfilling its basic objective? Is it OK to accept that we’ve always done it that way?

When I think about these questions, I think about bananas. I’ve always peeled bananas from the stem. It works reasonably well most of the time. But occasionally the stem breaks off awkwardly and mashes the end of the banana. I’ve also noticed recently that snapping the stem can aggravate the arthritis in my thumbs. But, hey – it’s not a big deal. I’ve always done it that way. Why would I change something that’s not broken?

Then I learned that monkeys peel a banana from the opposite end. This is actually the top since bananas grow “upside down”. You simply pinch the top and the peel separates; then you pull it back. It’s simple, easy to do, essentially foolproof, and it doesn’t hurt arthritic thumbs. (Here’s an illustrated guide).

Now I peel bananas from the top rather than from the bottom. Each time I do, I think about innovation. It’s a simple thought – I should ask more questions about how I do things. Why do we things the way we do? It’s a simple process – we just observe and question. It’s so simple, in fact, that we can learn it from monkeys.