The Carat Contest. Who Wins?

I win!

Let’s say that I buy my wife a two carat diamond ring. At the same time, you buy your wife a one carat diamond ring. Let’s also assume that the diamond I buy is not very good quality — it has a few flaws, the cut is not great, and the color is a little off. Your diamond, on the other hand, is superb — it’s flawless and clear and the cut is spectacular. In fact, though the diamond you bought is half the size of the one I bought, your diamond cost more — maybe quite a bit more.

So, in the Best Husband Sweepstakes, who won? Well, I did. Even though it takes four C’s (cut, color, clarity, and carat weight) to measure a diamond’s quality, people really only talk about carats. When your wife flashes her diamond, no one asks, “Gosh, what clarity is it?” The only question is, “Wow, how many carats is that thing?” You bought a better diamond but I win the opinion poll.

It hardly seems fair, does it? You’ll know in your heart of hearts that your wife has a better ring. So will she. But in the “marketplace” of public opinion, two carats is better than one.

What does this have to do with strategy, innovation, and brand? All too often, companies and individuals really don’t understand how they’re being judged. It’s useful to take a step back and determine how the league table is really being compiled. Here are some examples:

- I thought my last company, Lawson Software, was doing a very good job at improving customer satisfaction. But what about our stock price? It was doing reasonably well, considering all the changes, but it wasn’t outpacing the market. So another company bought us. Our customers were getting happier but they were no longer our customers.

- Landline telephone companies thought they were being evaluated on the quality of their calls. Did it sound like the person you were calling was right next door? That was important up to a point but, beyond that point, mobility and convenience were much more important. The landline companies were toast.

- Your local bookstore thought it was being judged on the quality of its collection and customer service. That worked well for a long time. Then people decided that what they really wanted was the information inside the book rather than the physical book itself. Ooops!

Do you really know how you (or your company) are being judged? Maybe it’s time to step back, look around, and re-evaluate. Ask around. Do some research. Evaluate what other people are evaluating. It’s good to know about cut, color, and clarity. It’s crucial to know about carats.

Improve Your Vision (Statement)

Several clients have recently asked me to help them craft their vision statements. So, what makes for a good vision statement? Let’s

start with a few of my favorites:

Google: To organize the world’s knowledge and make it useful.

Lawson: We make our customers stronger.

University of Denver: A private school dedicated to the public good.

US Air Force: Fly, Fight, and Win.

Denver Public Schools: Every Child Succeeds.

National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS): A World Free of MS

- Keep it short — no more than a dozen words. You want it to be memorable.

- Put customer requirements first — too many vision statements start with what the company does. In my opinion, that’s a mission statement. The vision statement summarizes your impact on your customers or the world at large.

- Know the difference between mission and vision. A mission statement is more about how we do things. A vision statement is about what happens to the world when we do those things.

- Use the “so what/ so that” process to get to ultimate benefits — start with a statement of what your company does. Then ask yourself, “so what?” Answer with a “so that” statement. Repeat the process until you get to a logical conclusion — that’s probably the benefit you want to focus on. So, let’s say you provide services to hospitals. You start with:

We provide world-class services to hospitals…

So what?

…so that hospitals will be more effective …

So what?

…. so that hospitals can save more lives.

- Imagine end states, even if they put you out of business — the vision statement of NMSS is, “A World Free of MS”. When we achieve that, NMSS will no longer be needed.

- Verbs are good — I like the US Air Force statement: four words, three of which are verbs. Active verbs (and actions in general) are memorable.

- The verb “to be” is not your friend — it’s lazy and verbose. None of my favorite statements include it.

- Ditto for the verb “to strive” — in your vision statement, don’t strive to do something. Just do it. (Where have I heard that before?)

- It’s not just words, it’s culture — you can develop elegant phrases but, if they don’t fit your culture, you’ll just create cynicism.

- Live it — it’s good to write a statement, it’s better to have it absorbed into your employees’ hearts, and minds, and actions. The only way to do that is to set the example and live the words, even when it’s painful to do so.

Branding and Archetypes

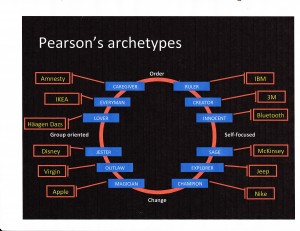

As you develop your company’s brand, how do you determine what “personality” you should project? How do you know where your brand fits relative to other brands in the market? I always recommend that you do as much market research as you can. I also recommend that you study the archetypal systems developed by Carol Pearson (whose website is here).

As you develop your company’s brand, how do you determine what “personality” you should project? How do you know where your brand fits relative to other brands in the market? I always recommend that you do as much market research as you can. I also recommend that you study the archetypal systems developed by Carol Pearson (whose website is here).

Pearson is a Jungian psychologist more than a marketing maven. She has developed a set of archetypes that help people understand how to use their inner resources to enrich their lives. Fortunately for us marketing types, these archetypes can also be applied to companies and organizations. They can help you understand how you fit into a broader ecosystem and how to convey your message most effectively.

When I worked at Lawson Software, we used the simplified diagram that you see here. The diagram includes 12 basic archetypes with a company to illustrate each one.

The circle helps you understand how the archetypes fit together. For instance, note the word “Order” at the top of the circle and the word “Change” at the bottom. Simply put, the companies on the top half of the circle want to maintain the existing order, the current market structure. By comparison, the companies on the bottom half might be described as “upstarts”. They want to change — or overthrow — the current market structure.

The left and right halves of the circle also have much to tell us. The archetypes on the left side are group-oriented. Those on the right side are more self-focused. The simplest explanation is that those companies on the left of the circle focus primarily on their external constituencies. Those on the right focus more attention on internal processes and procedures.

At Lawson, we quickly decided that we were on the bottom half of the circle. We weren’t the market leaders, we didn’t dominate the segment — we needed to shake things up to find our place in the sun. Similarly, we decided that we were on the left side of the circle. We were market oriented and our mission was to make our customers stronger. In other words, we were externally focused.

So, we were on the lower left segment of the circle. We had three archetypes to choose from: 1) Jester, like Disney; 2) Outlaw, like Virgin; 3) Magician, like Apple. We then proceeded by elimination. We were a B2B company and just didn’t have the magical chops of Apple. Similarly, we weren’t a jester like Disney. Indeed, we were probably too serious.

That left us at “Outlaw”. We never really liked that label but ultimately we decided that’s who we were. (We described ourselves as “disrupters” rather than as “outlaws” but, really, what’s the difference?) To succeed, we needed to break some rules. We needed to be different and shake things up. It helped that we had a plain-spoken and charismatic CEO who was not unlike Richard Branson.

Choosing the outlaw/disrupter path almost immediately led us to use a cartoon character — very different than what you would expect from, say Oracle or SAP. With help from Fiftyeight, a very creative agency in Germany, we developed the Lars Lawson character as well as Sepp (for SAP) and ElCaro (Oracle spelled backwards). We then launched a series of video adventures on YouTube that typically garnered over a million views. (You can see the most popular videos here and here).

Did it work? You betcha. We grew faster than our segment and gained visibility globally. Bottom line: whether you’re a person or a company, it helps to know who you are and where you fit.

You can find Carol Pearson’s books here.

Make a Brand Promise or Keep a Brand Promise?

I promise.

You have $10,000 left in your marketing budget. Should you use it to make a brand promise or to keep a brand promise?

It’s a tricky question and one that Bain & Company tries to answer in a newly released white paper. (Click here). As Bain points out, we often think of branding as a way to create an emotional attachment with a consumer. Bain suggests a different approach: we create brands to shift demand. With a strong brand, we may shift demand to higher prices or greater volume or, maybe, some of both.

As we build brands, we need to make brand promises. This often involves emotional advertising and direct marketing. On the other hand, for a mature brand in an established market, more advertising may deliver diminishing returns. Rather than shifting demand, we’re just spending money in a senseless arms race.

Bain gives four examples of fashion retailers that take very different approaches to brand promises. At one end of the spectrum, American Apparel and Benetton advertise heavily and often provocatively. In other words, they’re making promises. However, recent results — stagnant at best — suggest that they’re not keeping promises.

At the other end of the spectrum, Patagonia spends far less on advertising but has invested heavily in environmental causes. Patagonia’s strong word-of-mouth momentum focuses on promises kept. Similarly, the fashion retailer, Zara, does no advertising at all. Through smart locations, however, and short, fast production runs, they’ve built a strong company. The chatter about Zara also focuses on promises kept. For both Patagonia and Zara, the results have included faster growth and higher margins than almost all their competitors.

Bain argues that brand equity is really a brand’s power to shift demand. To illustrate, the authors review brand equity for 21 different product categories. (The research is based on discrete choice analysis, which I’ll describe in more detail in the near future). The research isolates different elements of the consumer decision — allowing us to compare the power of pricing, brand, and specific features. For MP3 players, for instance, the leading brand captures 38.5% of consumer choice based on brand alone. This compares to 13.9% for the second strongest brand. In other words, the leading brand was 2.9 times more powerful than the second brand in shifting demand.

Brands were powerful in both B2C and B2B categories. Many authors have suggested that brands are not as important in B2B categories — that B2B purchase decisions are not “emotional”. The Bain study suggests otherwise. As the authors write, “Companies have built strong brands even in … B2B … categories such as construction tools and medical devices. On construction sites, the loyalty to tool brands runs as deep as the passion that fashionistas demonstrate for their favorite jeans.”

Think about your brand — whether corporate or personal. Do you need to attract attention by making more brand promises? Or do you need to build loyalty by fulfilling brand promises? Either way, consider the power you have to shift demand simply by the way you behave.

Branding: The Value of Face Time

We need some face time.

Long ago, when I was a product manager at Solbourne Computer, we were trying to answer some nagging questions about our market. We built very fast symmetric multiprocessing Unix servers — back when symmetric multi-processing (SMP) was a brave new thing. In the early going, our machines were essentially hand built and we had difficulty meeting demand. As we worked our way down the manufacturing curve, however, we learned how to build machines more quickly. It soon became clear that we could not only satisfy demand but exceed it.

So we needed more demand. To identify potential sources of demand, we studied all of our sales to date. What patterns could we identify? Unfortunately, the raw data revealed almost nothing. There were no real patterns in terms of SIC code, geography, or industry. We had sold servers to national laboratories, astronomical observatories, large companies, medium-sized companies, universities, B2B companies, B2C companies, and so on.

Since we couldn’t identify any clear patterns in the data, we decided to go out and meet our early customers. We reached out to all of our customers and requested face-to-face meetings. Ultimately, we scheduled meetings with about 50 different customers.

As we returned from our customer calls, we held lengthy meetings to discuss the results. Again, no patterns emerged. Finally, someone suggested that we simply describe our customers. Were they fat or thin? Short or tall? Old or young? Frankly, I thought that was a dumb idea but it turned out to be brilliant. As we began describing the customers, a very clear pattern emerged. First, they were all men. Second, they were in their early to mid 30s. Third, they were all heads of their department. Titles varied but they were what we would today call the CIO. Fourth, and most important, they had recently replaced a much older manager. They were new in their positions and wanted to make their mark.

Why did they buy Solbourne? We were a small company with hot new technology — symmetric multiprocessing. But we also ran on the Unix operating system — a very safe choice. Further, the benefits of SMP were well understood — the concepts were proven though the technology was new. So newly installed, youngish CIOs could use us to demonstrate that the old regime was out; a new regime was in. They could look bold without worrying too much about failure. When we figured this out, one of our pithier sales reps said, “Geez… it’s like dogs peeing on a wall. They’re using our machines to mark their territory.” All we had to do then was to figure out where the new CIOs were. But that’s a different story.

So, what’s the moral of the story? We thought we were selling very sophisticated, state-of-the-art servers. But actually, we were fulfilling a psycho/social need. We gave our buyers signaling equipment. With Solbourne servers, they could signal that they had arrived. It was a sobering lesson in selling technology. It’s often not the technology that matters but rather the (often unspoken) need the technology addresses. It’s also a lesson in the power of face-to-face meetings. If we hadn’t met our customers personally, we never would have figured it out.