Baseball, Big Data, and Brand Loyalty

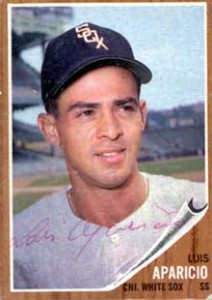

My hero.

I started smoking in high school but didn’t settle on “my” brand until I got to college. My Dad smoked Camels for most of his life but I decided that was not the brand for me. (Cough, hack!) Ultimately, I settled on Marlboros.

How I made that decision is still a mystery to me. In its very earliest days, Marlboro was positioned as a “woman’s brand” with slogans like “Ivory tips protect the lips” and “Mild as May”. That didn’t work very well, so the brand changed its positioning to highlight rugged cowboys in the American west. The brand took off and along the way I got hooked.

Though I don’t know why I chose Marlboros, I do know that it was a firm decision. I smoked for roughly 20 years and I always chose Marlboro. This is why brand owners focus so much attention on the 18-to-24 year-old segment. Brand preferences established in those formative years tend to last a lifetime.

But brand preferences often form quite a bit earlier. Brand owners may actually be late to the party. For example, I chose my baseball team preferences when I was much younger.

I played Little League baseball and was crazy about the sport. In our league, the teams were named after big league teams. Even though we lived in Baltimore, I played shortstop and second base for the Chicago White Sox. (The book on me: good glove/no bat).

At the time, Luis Aparicio and Nellie Fox played shortstop and second base for the real Chicago White Sox. They were my heroes. I knew everything about them, including the fact that they both weighed about 150 pounds in the pre-steroid era. I formed an emotional connection with the White Sox at the age of 10 or 11 and I still follow them.

My brand loyalty even rubbed off on the “other” team in Chicago, the Cubbies. Their shortstop was the incomparable Ernie Banks. I had heard of the Holy Trinity and I assumed that it was composed of Luis, Nellie, and Ernie.

I thought about all this when I opened the New York Times this morning and read about the nexus of Big Data, Big League Baseball, and Brand Development. Seth Stephens-Davidowitz has used big data to probe fan loyalty to various major league teams. (Unfortunately, he omits the White Sox).

Among other things, Stephens-Davidowitz looks at fans’ birth years and finds some interesting anomalies. For instance, an unusually large number of New York Mets fans were born in 1961 and 1978. Why would that be? Probably because boys born in those years were eight years old when the Mets won their two World Series championships. Impressionable eight-year-old boys formed emotional attachments that last a lifetime.

How much is World Series championship worth? Most brand valuations focus on how a championship affects seat, television, and auxiliary revenues. Stephens-Davidowitz argues that this approach fundamentally undervalues the brand because it omits the value of lifetime brand loyalty. When he recalculates the value with brand loyalty factored in, he concludes that “A championship season … is at least twice as valuable as we previously thought.”

What’s a brand worth? As I’ve noted elsewhere, it’s hard to measure precisely. But we form emotional attachments at very early ages and they last a very long time. As Stephens-Davidowitz concludes, “…data analysis makes it clear that fandom is highly influenced by events in our childhood. If something captures us in our formative years, it often has us hooked for life.”

Make a Brand Promise or Keep a Brand Promise?

I promise.

You have $10,000 left in your marketing budget. Should you use it to make a brand promise or to keep a brand promise?

It’s a tricky question and one that Bain & Company tries to answer in a newly released white paper. (Click here). As Bain points out, we often think of branding as a way to create an emotional attachment with a consumer. Bain suggests a different approach: we create brands to shift demand. With a strong brand, we may shift demand to higher prices or greater volume or, maybe, some of both.

As we build brands, we need to make brand promises. This often involves emotional advertising and direct marketing. On the other hand, for a mature brand in an established market, more advertising may deliver diminishing returns. Rather than shifting demand, we’re just spending money in a senseless arms race.

Bain gives four examples of fashion retailers that take very different approaches to brand promises. At one end of the spectrum, American Apparel and Benetton advertise heavily and often provocatively. In other words, they’re making promises. However, recent results — stagnant at best — suggest that they’re not keeping promises.

At the other end of the spectrum, Patagonia spends far less on advertising but has invested heavily in environmental causes. Patagonia’s strong word-of-mouth momentum focuses on promises kept. Similarly, the fashion retailer, Zara, does no advertising at all. Through smart locations, however, and short, fast production runs, they’ve built a strong company. The chatter about Zara also focuses on promises kept. For both Patagonia and Zara, the results have included faster growth and higher margins than almost all their competitors.

Bain argues that brand equity is really a brand’s power to shift demand. To illustrate, the authors review brand equity for 21 different product categories. (The research is based on discrete choice analysis, which I’ll describe in more detail in the near future). The research isolates different elements of the consumer decision — allowing us to compare the power of pricing, brand, and specific features. For MP3 players, for instance, the leading brand captures 38.5% of consumer choice based on brand alone. This compares to 13.9% for the second strongest brand. In other words, the leading brand was 2.9 times more powerful than the second brand in shifting demand.

Brands were powerful in both B2C and B2B categories. Many authors have suggested that brands are not as important in B2B categories — that B2B purchase decisions are not “emotional”. The Bain study suggests otherwise. As the authors write, “Companies have built strong brands even in … B2B … categories such as construction tools and medical devices. On construction sites, the loyalty to tool brands runs as deep as the passion that fashionistas demonstrate for their favorite jeans.”

Think about your brand — whether corporate or personal. Do you need to attract attention by making more brand promises? Or do you need to build loyalty by fulfilling brand promises? Either way, consider the power you have to shift demand simply by the way you behave.

Branding: Free The GM Five!

Once upon a time, General Motors had five major brands. Why five? Because there were five decades in the car buying experience. GM had a car for every need and every age.

Back in the day (my Dad’s day), everyone understood how to buy GM brands. Chevrolet was for young couples in their twenties, just starting out in life. In your thirties, you traded up to a Pontiac — a little nicer, not quite so bare bones. Oldsmobile was the choice for forty-somethings — a good middle of the road brand. In your fifties, you opted for a Buick — more luxury, near top-of-the-line. When you reached your sixties (and beyond), you wanted to signal that you had made it — so you bought a Cadillac.

In the late 80s, Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities had a good line comparing a European brand with GM. One of Wolfe’s characters talks about getting rich and buying a Mercedes. Another character responds, “Oh, a Mercedes is just what a Buick used to be.” I recently bought a large Volvo sedan. I like it a lot but I also think, “Oh, it’s just a Swedish Cadillac”.

So, what happened to GM? They stopped building brands and started building cars. Instead of clearly differentiating their brands, they decided to aim for manufacturing efficiency by consolidating platforms, parts, and styling. They may have saved some money on the manufacturing line but they wound up producing indistinguishable cars. Whey would I pay more for a Buick when it looks just like a Chevy? GM reached the nadir with the Cadillac Cimarron — a re-badged Chevy Citation. A GM engineer was asked, “What’s the difference between a Citation and a Cimarron?” He famously replied, “About $5,000”.

What’s the lesson here? Brands belong to buyers, not sellers. GM thought they owned the brands and could treat them to a dose of industrial efficiency. The move made sense from a manufacturing perspective but not from a brand perspective. Once the brands lost their distinction, they also lost their markets.

It’s probably time to review your brands. Don’t review them based on features or functions — that’s the way sellers think. Rather, review your brands based on which markets they appeal to. Are those markets really different from each other? If they are, then keep accentuating the brand differences. If they all appeal to essentially the same market, however, you may want to consolidate your brands. There’s no point keeping five brands around if potential buyers can’t tell them apart.