Baseball, Big Data, and Brand Loyalty

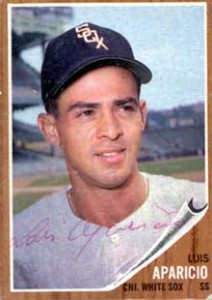

My hero.

I started smoking in high school but didn’t settle on “my” brand until I got to college. My Dad smoked Camels for most of his life but I decided that was not the brand for me. (Cough, hack!) Ultimately, I settled on Marlboros.

How I made that decision is still a mystery to me. In its very earliest days, Marlboro was positioned as a “woman’s brand” with slogans like “Ivory tips protect the lips” and “Mild as May”. That didn’t work very well, so the brand changed its positioning to highlight rugged cowboys in the American west. The brand took off and along the way I got hooked.

Though I don’t know why I chose Marlboros, I do know that it was a firm decision. I smoked for roughly 20 years and I always chose Marlboro. This is why brand owners focus so much attention on the 18-to-24 year-old segment. Brand preferences established in those formative years tend to last a lifetime.

But brand preferences often form quite a bit earlier. Brand owners may actually be late to the party. For example, I chose my baseball team preferences when I was much younger.

I played Little League baseball and was crazy about the sport. In our league, the teams were named after big league teams. Even though we lived in Baltimore, I played shortstop and second base for the Chicago White Sox. (The book on me: good glove/no bat).

At the time, Luis Aparicio and Nellie Fox played shortstop and second base for the real Chicago White Sox. They were my heroes. I knew everything about them, including the fact that they both weighed about 150 pounds in the pre-steroid era. I formed an emotional connection with the White Sox at the age of 10 or 11 and I still follow them.

My brand loyalty even rubbed off on the “other” team in Chicago, the Cubbies. Their shortstop was the incomparable Ernie Banks. I had heard of the Holy Trinity and I assumed that it was composed of Luis, Nellie, and Ernie.

I thought about all this when I opened the New York Times this morning and read about the nexus of Big Data, Big League Baseball, and Brand Development. Seth Stephens-Davidowitz has used big data to probe fan loyalty to various major league teams. (Unfortunately, he omits the White Sox).

Among other things, Stephens-Davidowitz looks at fans’ birth years and finds some interesting anomalies. For instance, an unusually large number of New York Mets fans were born in 1961 and 1978. Why would that be? Probably because boys born in those years were eight years old when the Mets won their two World Series championships. Impressionable eight-year-old boys formed emotional attachments that last a lifetime.

How much is World Series championship worth? Most brand valuations focus on how a championship affects seat, television, and auxiliary revenues. Stephens-Davidowitz argues that this approach fundamentally undervalues the brand because it omits the value of lifetime brand loyalty. When he recalculates the value with brand loyalty factored in, he concludes that “A championship season … is at least twice as valuable as we previously thought.”

What’s a brand worth? As I’ve noted elsewhere, it’s hard to measure precisely. But we form emotional attachments at very early ages and they last a very long time. As Stephens-Davidowitz concludes, “…data analysis makes it clear that fandom is highly influenced by events in our childhood. If something captures us in our formative years, it often has us hooked for life.”