Brand Names: Offense

My clients often ask me to help them name things. They’re hoping that we can develop a name that plays equally well to logic and emotion and that states a compelling benefit in 15 letters or less. A lot of brains have been damaged this way.

My clients often ask me to help them name things. They’re hoping that we can develop a name that plays equally well to logic and emotion and that states a compelling benefit in 15 letters or less. A lot of brains have been damaged this way.

Great brand names often trigger emotional responses. But we often get the cause and effect backward. The name doesn’t put the emotion in us. We put the emotion in the name.

I worked in college and scraped together enough money to buy a beat-up Pontiac Tempest. The original Pontiac was a great Indian leader in the midwestern United States. The town of Pontiac, Michigan was named after him. General Motors opened a factory there and named the car after the town. Originally, the name Pontiac didn’t mean anything more to me than, say, the name Cotopaxi. It’s just a name. Then I bought the car and enjoyed driving it. Now Pontiac has a special meaning to me, some sentimental value. The name didn’t do anything to me. I did something to the name. That’s why naming is so difficult. The name doesn’t trigger anything until customers add emotion to it.

As Kevin Lane Keller and many other branding experts have pointed out, you can play offense or defense with a name — but it’s hard to do both. Consider three variables for offense:

- Memorability — anything you can do to make your name memorable will help build your brand. This may mean playing off a well-known word — as in Lincoln cars or Winston cigarettes. Be sure to link to something that has positive connotations. Repetition also builds memorability which is why marketers repeat themselves so often.

- Meaningfulness — a good name may identify a product category, or some key product features, or a major product benefit. Be aware that changes in perception may require you to change your name. When fried food came to be viewed as unhealthful, Kentucky Fried Chicken decided to change its name to KFC.

- Likability — it’s hard to know what makes a name likable. You may pick a popular person’s name. Animals often provide better names than people do. It’s hard to hate an animal whereas it’s not so hard to dislike some people. The more abstract a product or service is, the more important it is to focus on a likable name.

Democracies Surface Conflict

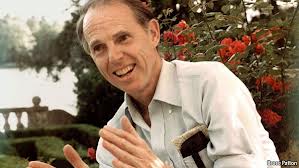

Roger Fisher died a few weeks ago. I wonder what he would have thought of today’s election.

Roger Fisher died a few weeks ago. I wonder what he would have thought of today’s election.

Fisher wrote (with varying co-authors) Getting to Yes which pioneered the concepts of principled negotiation. The idea is simple: negotiations should lead to collaboration and compromise. Both sides should have a stake in the solution. One side shouldn’t have to “give in”. It shouldn’t be winner take all.

Fisher also pointed out that democracies surface dissension and conflict. In the introduction to the 3rd edition, Fisher argues, “Democracies surface rather than suppress conflict, which is why democracies often seem so quarrelsome and turbulent when compared with more authoritarian regimes. … The goal cannot and should not be to eliminate conflict. Conflict is an inevitable — and useful — part of life. It often leads to change and generates insight. … And it lies at the heart of the democratic process, where the best decisions result not from superficial consensus but from exploring different points of view and searching for creative solutions. Strange as it may seem, the world needs more conflict not less.”

We have a lot of dissension in America today. That doesn’t bother me. We should disagree. What disheartened me about the recent campaigns were the attempts to invalidate each other: “If you don’t agree with me, you’re not a real American.” “The Founding Fathers said X. If you don’t agree with my interpretation of what they said, you’re unAmerican.”

To me, statements like these are truly unAmerican. People who call others unAmerican are not trying to reason with the opposition or even to argue a point. They’re trying to suppress or eliminate the opposition. The argument goes like this, “If you’re not a real American, you have no standing. We don’t need to consider your views. You don’t count. We’ll do what we want. You’re nobody.” It’s insulting and demeaning to invalidate a fellow American. The American Dream says we all count.

The Founding Fathers said a lot of different things but what they created is a system that requires collaboration and compromise. The system of checks and balances actually works, except in the face of intransigence. As numerous historians have pointed out, the genius of the American system is our ability to compromise.

I’m not particularly loyal to either political party but I am loyal to the process. I like to argue because I think it’s the best way to reach agreement. I’m worried that we’re losing not just the ability to compromise but also the desire. That would be a tragedy. So, no matter who wins today, I hope we can spend less time invalidating each other and more time getting to yes.

(You can find Roger Fisher’s obituary here. You can find Getting to Yes here.)

Multitasking is a Myth

I’ve never been able to pay attention to more than one thing at a time. I always assumed that this was a shortcoming on my part. I have friends who claim to be good multitaskers — attending to multiple projects and sources of information at the same time. I can focus on a task for hours on end but I’ve never been able to do two things at once. I always envied my multitasking friends.

Then last week, I attended a presentation by Bridget Arend, a professor of psychology at the University of Denver. Discussing how the brain works, she dropped an important tidbit: multitasking is a myth. People don’t really do two things at once. Instead, they are speedy serial task switchers. (Let’s call them SSTSers).

The best SSTSers can shift quickly from one target to another and focus intently on whatever target is in front of them at the moment. They focus intently and shift quickly. I think of expert trap shooters who can aim quickly at one clay pigeon, shoot it, and then — just as quickly — re-focus on another clay pigeon. They would never dream of aiming at two pigeons at once — it just doesn’t work. Perhaps we need to forget the old saying that we can kill two birds with one stone. It doesn’t happen. Believing it does only leads us astray.

This has important implications for communications. First, if you want to communicate to me, be sure you have my attention. If you walk into my office when I’m intently focused on my computer, you may not get my attention for a few minutes. It’s often a good idea to suggest that we go out for a cup of coffee — change the scenery, change the context, and allow me to re-focus. As Suellen can attest, I sometimes look straight at her and yet fail to hear anything she says.

Similarly, audiences don’t multitask well. You need a good introduction to grab their attention and get them to re-focus on you rather than whatever they were thinking about before. Some speakers love to show text-heavy slides while continuing to talk at normal presentation speed. They’re assuming that filling two channels — eyes and ears — will increase the impact. Actually, it’s just the opposite — the two channels cancel each other out. Sooner or later, each audience member attends to one channel or the other. Visual learners (a majority of us) tend to look at the slides while relegating you to oblivion.

This is also a good reason not to mention anything even remotely sexual in your speeches. Rest assured that sex is wildly more interesting than anything you’re talking about. If you mention sex, a good chunk of your audience will wander off on that track, never to return to your track. Sex is the ultimate serial task. Even the best SSTSers can’t switch quickly from that track to another. So, now that you’re thinking about sex, it’s time for me to sign off. I’m not going to get your attention back. See you tomorrow.

Innovation and Diversity

Do you have an MBA? So do most of the people I work with at my client organizations. One of the ways I add value is merely by the fact that I don’t have an MBA.

It’s not that having an MBA is a bad thing. It’s that so many companies are run by people educated in the same way — they all have MBAs. The fact that I don’t have an MBA doesn’t mean that I think better than they do. But I do think differently. Sometimes that creates problems. Oftentimes, it creates opportunity.

If all your employees think alike, then you limit your opportunity to be creative. Creativity comes from connections. By connecting concepts or ideas in different ways, you can create something entirely new. This works at an individual level as well as an organizational level. If you read only things that you agree with, you merely reinforce existing connections. If you read things that you disagree with, you’ll create new connections. That’s good for your mental health. It’s also good for your creativity.

At the organizational level, connecting new concepts can lead to important innovations. Indeed, the ability to innovate is the strongest argument I know for diversity in the workforce. If you bring together people with different backgrounds and help them form teams, interesting things start to happen.

In this sense, “diversity” includes ethnic, economic, and cultural diversity. It especially includes academic diversity. As a leader, you want your engineers, say, to mix and mingle with your humanities graduates. Perhaps your lit majors could improve your MBAs’ communication skills. Perhaps your philosophers can help you see things in an entirely new light. In today’s world, innovation requires that you bring together insights from multiple disciplines to “mash up” ideas and create new ways of seeing and doing.

Most companies keep data on ethnic diversity within their workforce. However, they don’t usually keep statistics on the different academic specialties represented among their employees. You may well have enough MBAs. But do you have enough linguists? Philosophers? Sociologists? Anthropologists? Artists? If not, it’s time to start recruiting. The result could well be a healthier, more innovative company.