Marissa Mayer — You Go, Girl!

Marissa Mayer, the new Mom who is also the CEO of Yahoo!, recently announced that all Yahoos (that’s what they call employees) have to work at the office, not from home. Since then, the blogosphere has been all aflutter. A majority of the bloggers I’ve read suggest that Mayer is retrograde, dumb, and sexist. I have to disagree. I think it’s a very smart move and about time, too.

Marissa Mayer, the new Mom who is also the CEO of Yahoo!, recently announced that all Yahoos (that’s what they call employees) have to work at the office, not from home. Since then, the blogosphere has been all aflutter. A majority of the bloggers I’ve read suggest that Mayer is retrograde, dumb, and sexist. I have to disagree. I think it’s a very smart move and about time, too.

The arguments against Mayer’s decision have to do with productivity, convenience, women’s rights, and maybe even clean air. Stephen Dubner (one of the two Steves who created Freakonomics) wrote that an experiment at a Chinese travel agency shows that woking at home can increase your productivity and reduce health problems. Apparently long commutes raise your blood pressure. A recent article from Stanford (based on the same Chinese study) suggests that the productivity of those working at home is 13% greater than those working at the office. An article on WAHM.com (Work At Home Moms) argues that telecommuting shifts the employee’s emphasis away from politics and towards performance. Months ago, Slate wrote that Mayer doesn’t care about sexism. Grindstone calls Mayer’s decision a “morale killer” and a “giant leap backward for womankind.” The Atlantic Monthly flatly declares that “Marissa Mayer Is Wrong”.

But is she wrong? It depends on what she’s trying to do. Raising productivity is generally a good idea. But if the price of productivity is reduced innovation, then the cost is too high. There’s a strong case to be made that working from home — while it provides many benefits — inhibits innovation. I’ve written about the mashup nature of innovation. Many of the best new ideas are mashups of existing ideas.

The same logic applies to people. Getting people together — and encouraging them to mix and mingle in more-or-less random ways — helps them mash up concepts and create new ideas. It’s why Building 20 — a ramshackle, “temporary” structure on the MIT campus — generated so many innovations. People bumped into each other and shared ideas and, in doing so, created everything from generative grammar to Bose acoustics. It’s why cities produce a disproportionate share of of inventions and patents (click here and here). It’s why reducing the number of bathrooms in a building will increase innovation –you’re more likely to bump into someone. It’s why I advise my clients to allow e-mail to flow freely between buildings but to banish it within a building. If you’re in the same building as the recipient, get together for a face-to-face meeting. You’ll get more out of it — maybe even an innovative new product.

So, what is Mayer trying to accomplish? In her memo to all Yahoos, she speaks of “communication and collaboration” and notes that “Some of the best decisions and insights come from hallway and cafeteria discussions, meeting new people, and impromptu team meetings.” She doesn’t use the word “innovation” but that’s exactly what she’s talking about. And, in my humble opinion, Yahoo! could use a healthy dose of innovation. So I think Mayer has got it right: PPPI — proximity and propinquity propel innovation. All I can say is: you go, girl!

Sunday Shorts – 9

Interesting things I’ve spotted this week.

Boston Consulting Group highlights the most innovative companies of 2012. What makes them more innovative than your company?

What makes beautiful things beautiful? What’s the perfect ratio of fractals to non-fractals and how did Jackson Pollock know it? Maybe the secret of beauty is buried in our genes.

The rate of growth in health care costs has slowed dramatically over the past four years. Now why would that be?

Spending on health care construction has also dropped precipitously. See the most important health care chart that nobody is talking about.

Do you flush your Valium down the toilet? You could be causing fish to join gangs and drop out of schools.

What happens to the thermostat when it’s re-designed by the people who designed the iPhone and the iPod?

Sunday Shorts – 5

Some interesting things I spotted this week, whether they were published this week or not.

The Economist asks, will we ever again invent anything that’s as useful as the flush toilet? Is the pace of innovation accelerating or decelerating? And what should we do about it, if anything?

When we think about innovation, we often focus on ideas and creativity. How can we generate more good ideas? But what about the emotional component of innovation? For innovative companies, emotional intelligence may trump technical intelligence. Norbert Alter answers your questions from Paris.

We’re familiar with the platform wars for mobile applications. Will Apple’s iOS become the dominant platform? Or maybe it will be Android from Google? Perhaps it’s some version of Windows? But what if the next great mobile app platform is a Ford or a Chevy? (Click here).

For my friends in Sweden, here’s McKinsey’s take on the future of the Swedish economy. Things are looking up — just don’t rest on your laurels.

Where does America’s R&D money go? Here’s an infographic that shows how the Federal government has invested in research over the past 50 years.

The Greeks had lots of tricks for memorizing things. They could hold huge volumes of information in their heads. But does memory matter anymore? After all, you can always Google it, no? William Klemm writes that there are five reasons why tuning up your memory is still important. And he’s a Texas Aggie so he must be right.

Innovation and Diversity

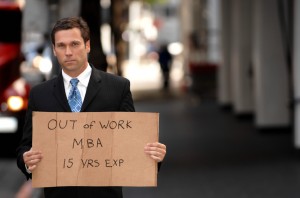

Do you have an MBA? So do most of the people I work with at my client organizations. One of the ways I add value is merely by the fact that I don’t have an MBA.

It’s not that having an MBA is a bad thing. It’s that so many companies are run by people educated in the same way — they all have MBAs. The fact that I don’t have an MBA doesn’t mean that I think better than they do. But I do think differently. Sometimes that creates problems. Oftentimes, it creates opportunity.

If all your employees think alike, then you limit your opportunity to be creative. Creativity comes from connections. By connecting concepts or ideas in different ways, you can create something entirely new. This works at an individual level as well as an organizational level. If you read only things that you agree with, you merely reinforce existing connections. If you read things that you disagree with, you’ll create new connections. That’s good for your mental health. It’s also good for your creativity.

At the organizational level, connecting new concepts can lead to important innovations. Indeed, the ability to innovate is the strongest argument I know for diversity in the workforce. If you bring together people with different backgrounds and help them form teams, interesting things start to happen.

In this sense, “diversity” includes ethnic, economic, and cultural diversity. It especially includes academic diversity. As a leader, you want your engineers, say, to mix and mingle with your humanities graduates. Perhaps your lit majors could improve your MBAs’ communication skills. Perhaps your philosophers can help you see things in an entirely new light. In today’s world, innovation requires that you bring together insights from multiple disciplines to “mash up” ideas and create new ways of seeing and doing.

Most companies keep data on ethnic diversity within their workforce. However, they don’t usually keep statistics on the different academic specialties represented among their employees. You may well have enough MBAs. But do you have enough linguists? Philosophers? Sociologists? Anthropologists? Artists? If not, it’s time to start recruiting. The result could well be a healthier, more innovative company.

Innovation: What’s Your Risk Profile?

Quick. What’s your risk profile? Do you like to take risks in business? If you do, you’ll probably seek and consume information in very different ways than your colleagues who are more risk averse. That can be a huge obstacle to innovation.

I often ask my clients to self-assess their appetite for risk on a scale of 1 to 6. People who are very averse to risk give themselves a “1”. People who love taking risks give themselves a “6”. In most cases, my clients distribute themselves along a more-or-less normal curve — a few 1s and 6s and many more 3s and 4s. To innovate successfully, you’ll need people in every category. If you have only 1s, you’ll never venture anything. If you have only 6s, you’ll take far too many risks for your own good.

The issue is that people with different risk profiles also have different information needs. That can stifle communication and that, in turn, can stifle innovation. People who are generally risk averse (in a business sense), want much more information than those who are risk oriented. People who are 1s often want very detailed business cases before making a decision. They want to identify every possible risk in the proposed venture and have contingency plans ready. They also like detailed spreadsheets; lots of quantitative data makes them feel comfortable.

Risk-oriented people, on the other hand, are quite comfortable with less information. They believe that it’s impossible to predict the future. A detailed spreadsheet is no better at predicting the future than a rough-and-ready guess. Further, you can’t control every variable. So, why bother creating detailed spreadsheets and exhaustive business plans? You have to dive in and experiment to learn what will work and what won’t.

To innovate successfully, you need both risk-oriented and risk-averse individuals. They see the world differently and that’s good. Your risk-oriented colleagues can help you spot new opportunities. Your risk-averse colleagues can help you avoid stupid mistakes. The trouble is that the two types of colleagues don’t know how to talk to each other effectively. They have different information needs that are very deeply ingrained and will probably never change. As a leader, you’ll need to step in and serve as an interpreter between the two groups. By doing so, you’ll hear both sides, get a balanced view, and pick those innovations that are most likely to work.