Should You Talk To Yourself?

Speak to me, wise one.

The way we think about the world comes from our body, not from our mind. If I like somebody, I might say, “I have warm feelings for her.” Why would my feelings be warm? Why wouldn’t I say, “I have orange feelings for her”? It’s probably because, when my mother held me as an infant, I was nice and toasty warm. I didn’t feel orange. I express my thoughts through metaphors that come from my body.

We all know that our minds affect our bodies. If I’m in a good mood mentally, my body may feel better as well. As I’ve noted before, the reverse is also true. It’s hard to stay mad if I force myself to smile.

The general field is referred to as metaphor theory or, more generally, as embodied cognition. Simply put, our bodies affect our thinking. Our brains are not digital computers, after all. They’re analog computers, using bodily metaphors to express our thoughts.

As it happens, I’ve used embodied cognition for years without realizing it. Before giving a big speech, I stand up straighter, flex my muscles, stretch out and up, and force myself to smile for 30 seconds. Then I’m ready. I didn’t realize it but I was practicing my bodily metaphors. I can speak more clearly (stand up straight), more powerfully (muscle flexing), and more cheerfully (smile), because of my warm-up routine.

My warm-up routine actually changes my hormones. As Amy Cuddy points out in her popular TED talk, practicing “power poses” for two minutes increases testosterone and reduces cortisol. The result is more dominance (testosterone) and less stress (cortisol). My body is priming me to give an exceptionally good speech. As Cuddy notes, it could also make me much more successful in a job interview.

I’m growing accustomed to the thought that the way I hold or move my body directly affects my thinking and mood. But what about my internal monologue? I talk to myself all the time. Is that a good thing? Do the words that I use in my monologue affect my thinking and behavior?

The answer is yes – for better and for worse. My “self-talk” affects how I perceive myself and that, in turn, affects how I behave. It’s also important how I address myself. Do I speak to myself in the first person – “I can do better than that.” Or do I speak to myself as someone else would speak to me – “Travis, you can do better than that.”

According to a recent article in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, the way I address myself makes a world of difference. If I speak as another person would address me, I gain more self-distance and perspective. I also reduce stress and make a better first impression. I can also give a better speech and will engage in “less maladaptive postevent processing”. (Whew!) In other words, I can perform better and feel better simply by choosing the right words in my internal monologue.

So, what’s it all mean? Take better care of your body to take better care of your mind. As my father used to say: “Look sharp, be sharp”. Oh… and watch your language.

(For an excellent article on how the field of embodied cognition has evolved, click here).

Thinking and Health

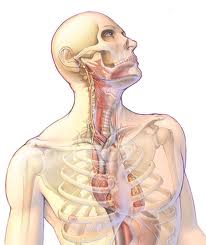

Does the mind influence the body or vice-versa? It seems that it happens both ways and the vagus nerve plays a key role in keeping you both happy and healthy (and creative).

Does the mind influence the body or vice-versa? It seems that it happens both ways and the vagus nerve plays a key role in keeping you both happy and healthy (and creative).

Also known as the tenth cranial nerve, the vagus nerve links the brain with the lungs, digestive system, and heart. Among many other things, the vagus nerve sends the signals that help you calm down after you’ve been startled or frightened. It helps you return to a “normal” state. A healthy vagus nerve promotes resilience — the ability to recover from stress. (The vagus nerve is not in the spinal cord, meaning that people with spinal cord injuries can still sense much of their system).

The vagus also helps control your heartbeat. To use oxygen efficiently, your heart should beat a bit faster when you breathe in and a bit slower when you breathe out. The ratio of your breathing-in heartbeat to your breathing-out heartbeat is known as the vagal tone.

Physiologists have long known that a higher vagal tone is generally associated with better physical and mental health. Most researchers assumed, however, that we can’t improve our vagal tone. Some lucky people have a higher vagal tone; some unlucky people have a lower one. It’s determined by factors beyond our control.

Then Barbara Fredrickson and Bethany Kok decided to see if that was really true. Their research – published in Psychological Science – suggests that we can improve our vagal tone. By doing so, we can create a virtuous circle: improving our mental outlook can improve vagal tone which, in turn, can make it easier to improve our mental outlook. (For two non-technical articles on this research, click here and here).

In their experiment, Fredrickson and Kok randomly divided volunteers into two groups. One group was taught a form of meditation (loving kindness meditation) that engenders “feelings of goodwill”. Both groups were also asked to keep track of their positive and negative emotions.

The results were fairly straightforward: “All the volunteers … showed an increase in positive emotions and feelings of social connectedness – and the more pronounced this effect, the more their vagal tone had increased ….” Additionally, those who meditated improved their vagal tone much more than those who didn’t.

The virtuous circle seems to be associated with social connectedness, which Fredrickson refers to as a “potent wellness behavior”. The loving kindness meditation promotes a sense of social connectedness. That, in turn, improves vagal tone. That, in turn, promotes a sense of social connectedness. Bottom line: it pays to think positive thoughts about yourself and others.

Thinking With Your Body

When I’m happy, I smile. A few years ago, I discovered that the reverse is also true: when I smile, I get happy. I’ve also found that standing up straight — as opposed to slouching — can improve my mood and perhaps even my productivity.

It turns out that I was on to something much bigger than I realized at the time. There’s increasing evidence that we think with our bodies as well as our minds. Some of the evidence is simply the way we express our thoughts through physical metaphors. For instance, “I’m in over my head”, “I’m up to my neck in trouble”, “He’s my right hand man”, and so on. Because we use bodily metaphors to express our mental condition, the field of “body thinking” is often referred to a metaphor theory. Perhaps more generally, it’s called embodied cognition.

In experiments reported in New Scientist and in Scientific American, we can see some interesting effects. For instance, with people from western cultures, “up” and “right” mean bigger or better while “down” or “left” mean smaller or worse. So, for instance, when volunteers were asked to call out random numbers to the beat of a metronome, their eyes moved upward when the next number was larger and moved downward when the next number was smaller. Similarly, volunteers were asked to gauge the number of objects in a container. When they were asked to lean to the left while formulating their estimate, they guessed smaller numbers on average. When leaning to the right, they guessed larger numbers.

In another experiment, volunteers were asked to move boxes either: 1) from a lower shelf to a higher shelf; or 2) from a higher shelf to a lower shelf. While moving the boxes, they were asked a simple, open-ended question, like: What were you doing yesterday? Those who were moving the boxes upward were more likely to report positive experiences. Those who were moving the boxes downward were more likely to report negative experiences.

When I speak of the future, I often gesture forward — the future is ahead of us. When I speak of the past, I often do the opposite, gesturing back over my shoulder. Interestingly, the Aymara Indians of highlands Bolivia are reported to do the opposite — pointing backward to the future and forward to the past. That seems counter-intuitive to me but the Aymara explain that the future is invisible. You can’t see it. It’s as if it’s behind you where it can quite literally sneak up on you. The past, on the other hand, is entirely visible — it’s spread out in front of you. That makes a lot of sense but my cultural training is so deeply embedded that I find it very hard to point backward to the future. It’s an interesting example of cultural differences influencing embodied cognition.

Where does this leave us? Well, it’s certainly a step away from Descartes’ formulation of the mind-body duality. The body is not simply a sensing instrument that feeds data to the mind. It also feed thoughts and influences our moods in subtle ways. Yet another reason to take good care of your body.