Critical Thinking Through the Ages

As I’m teaching a course on critical thinking, I thought it would be useful to study the history of the concept. What have leading thinkers of the past conceived to be “critical thinking” and how have their perceptions changed over time?

As I’m teaching a course on critical thinking, I thought it would be useful to study the history of the concept. What have leading thinkers of the past conceived to be “critical thinking” and how have their perceptions changed over time?

One of the earliest — and most interesting –references that I’ve found is a sermon called the Kalama Sutta preached by the Buddha some five centuries before Christ. Often known as the “charter of free inquiry”, it lays out general tenets for discerning what is true.

Many religions hold that truth is revealed through scriptures or through institutions that are authorized to interpret scriptures. By contrast, Buddhism generally asserts that we have to ascertain truth for ourselves. So, how do we do that?

That was essentially the question that the Kalama people asked the Buddha when he passed through their village of Kesaputta. The Buddha’s sermon emphasizes the need to question statements asserted to be true. Further, the Buddha goes on to list multiple sources of error and cautions us to carefully examine assertions from those sources. According to Wikipedia, the Buddha identified the following sources of error:

- Oral histories

- Tradition

- New sources

- Scripture or other official documents

- Supposition

- Dogmatism

- Common sense

- Opinion

- Experts

- Authorities or one’s own teacher

Further, “Do not accept any doctrine from reverence, but first try it as gold is tried by fire.” The requires examination, reflection, and questioning and only that which is “conducive to the good” should be accepted as truth.

As Thanissaro Bhikkhu summarizes it, “any view or belief must be tested by the results it yields when put into practice; and — to guard against the possibility of any bias or limitations in one’s understanding of those results — they must further be checked against the experience of people who are wise.”

So how do the Buddhist commentaries compare to other philosophers? In the century after Buddha, Socrates is quoted as saying, “I know you won’t believe me, but the highest form of Human Excellence is to question oneself and others.” Almost 2,000 years later, Francis Bacon wrote, “Critical thinking is a desire to seek, patience to doubt, fondness to meditate, slowness to assert, readiness to consider, carefulness to dispose and set in order; and hatred for every kind of imposture.” A few hundred years later, Descartes wrote, “If you would be a real seeker after truth, it is necessary that at least once in your life you doubt, as far as possible, all things.” A hundred years after that, Voltaire wrote about the consequences of a failure of critical thinking, “Anyone who has the power to make you believe absurdities has the power to make you commit injustices.”

As the Swedes would say, there seems to be a “bright red thread” that ties all of these together. Go slowly. Ask questions. Be patient. Doubt your sources. Consider your own experience. Judge the evidence thoughtfully. For well over 2,000 years our philosophers — both Eastern and Western — have been saying essentially the same thing. It seems that we know what to do. Now all we have to do is to do it.

More Thinking on Your Thumbs

Power differential.

Remember heuristics? They’re the rules of thumb that allow us to make snap judgments, using System 1, our fast, automatic, and ever-on thinking system. They can also lead us into errors. According to psychologists there are least 17 errors that we commonly make. In previous articles, I’ve written about seven of them (click here and here). Let’s look at four more today.

Association — word association games are a lot of fun. (Actually, words are a lot of fun). But making associations and then drawing conclusions from them can get you into trouble. You say tomato and I think of the time I ate a tomato salad and got sick. I’m not going to do that again. That’s not good hygiene or good logic. The upside is that word associations can lead you to some creative thinking. You can make connections that you might otherwise have missed. And, as we all know, connections are the foundation of innovation. Just be careful about drawing conclusions.

Power differential — did you ever work for a boss with a powerful personality? Then you know something about this heuristic. Socially and politically, it may be easier to accept an argument made by a “superior authority” than it is to oppose it. It’s natural. We tend to defer to those who have more power or prestige than we do. Indeed, there’s an upside here as well. It’s called group harmony. Sometimes you do need to accept your spouse’s preferences even if they differ from yours. The trick is to recognize when preferences are merely a matter of taste versus preferences that can have significant negative results. As Thomas Jefferson said, “On matters of style, swim with the current. On matters of principle, stand like a rock”.

Illusion of control — how much control do you really have over processes and people at your office? It’s probably a lot less than you think. I’ve worked with executives who think they’ve solved a problem just because they’ve given one good speech. A good speech can help but it’s usually just one step in a long chain of activities. Here’s a tip for spotting other people who have an illusion of control. They say I much more often than we. It’s poor communication and one of the worst mistakes you can make in a job interview. (Click here for more).

Loss and risk aversion — let’s just keep doing what we’re doing. Let’s not change things … we might be worse off. Why take risks? It happens that risk aversion has a much bigger influence on economic decisions than we once thought. In Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman writes about our unbalanced logic when considering gain versus loss — we fear loss more than we’re attracted by gain. In general terms, the pain of a loss is about double the pleasure of a gain. So, emotionally, it takes a $200 gain to balance a $100 loss. Making 2-to-1 decisions may be good for your nerves but it often means that you’ll pass up good economic opportunities.

To prepare this article, I drew primarily on Peter Facione’s Think Critically. (Click here) Daniel Kahneman’s book is here.

Branding and Archetypes

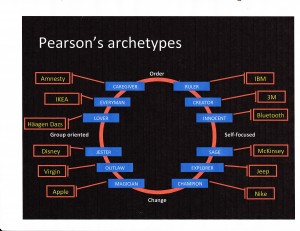

As you develop your company’s brand, how do you determine what “personality” you should project? How do you know where your brand fits relative to other brands in the market? I always recommend that you do as much market research as you can. I also recommend that you study the archetypal systems developed by Carol Pearson (whose website is here).

As you develop your company’s brand, how do you determine what “personality” you should project? How do you know where your brand fits relative to other brands in the market? I always recommend that you do as much market research as you can. I also recommend that you study the archetypal systems developed by Carol Pearson (whose website is here).

Pearson is a Jungian psychologist more than a marketing maven. She has developed a set of archetypes that help people understand how to use their inner resources to enrich their lives. Fortunately for us marketing types, these archetypes can also be applied to companies and organizations. They can help you understand how you fit into a broader ecosystem and how to convey your message most effectively.

When I worked at Lawson Software, we used the simplified diagram that you see here. The diagram includes 12 basic archetypes with a company to illustrate each one.

The circle helps you understand how the archetypes fit together. For instance, note the word “Order” at the top of the circle and the word “Change” at the bottom. Simply put, the companies on the top half of the circle want to maintain the existing order, the current market structure. By comparison, the companies on the bottom half might be described as “upstarts”. They want to change — or overthrow — the current market structure.

The left and right halves of the circle also have much to tell us. The archetypes on the left side are group-oriented. Those on the right side are more self-focused. The simplest explanation is that those companies on the left of the circle focus primarily on their external constituencies. Those on the right focus more attention on internal processes and procedures.

At Lawson, we quickly decided that we were on the bottom half of the circle. We weren’t the market leaders, we didn’t dominate the segment — we needed to shake things up to find our place in the sun. Similarly, we decided that we were on the left side of the circle. We were market oriented and our mission was to make our customers stronger. In other words, we were externally focused.

So, we were on the lower left segment of the circle. We had three archetypes to choose from: 1) Jester, like Disney; 2) Outlaw, like Virgin; 3) Magician, like Apple. We then proceeded by elimination. We were a B2B company and just didn’t have the magical chops of Apple. Similarly, we weren’t a jester like Disney. Indeed, we were probably too serious.

That left us at “Outlaw”. We never really liked that label but ultimately we decided that’s who we were. (We described ourselves as “disrupters” rather than as “outlaws” but, really, what’s the difference?) To succeed, we needed to break some rules. We needed to be different and shake things up. It helped that we had a plain-spoken and charismatic CEO who was not unlike Richard Branson.

Choosing the outlaw/disrupter path almost immediately led us to use a cartoon character — very different than what you would expect from, say Oracle or SAP. With help from Fiftyeight, a very creative agency in Germany, we developed the Lars Lawson character as well as Sepp (for SAP) and ElCaro (Oracle spelled backwards). We then launched a series of video adventures on YouTube that typically garnered over a million views. (You can see the most popular videos here and here).

Did it work? You betcha. We grew faster than our segment and gained visibility globally. Bottom line: whether you’re a person or a company, it helps to know who you are and where you fit.

You can find Carol Pearson’s books here.

Creativity in Five Steps

Just five more steps.

How does creativity happen? Is there a pattern — more or less standard — that we can repeat? Is there a process that can lead us from ordinary beginnings to extraordinary ends? Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi — while not guarateeing results — writes that creativity typically evolves through five stages.

The first stage is preparation. Basically, you need to know the rules before you break them. Thomas Kuhn writes that scientific paradigms reflect a basic consensus of how the world operates. Prior to Copernicus, the astronomical paradigm held that the earth was the center of the universe. Before Copernicus could change the paradigm, he had to immerse himself in it. Only then could he make the observations that changed the paradigm.

The second phase is incubation, “… during which ideas churn around below the threshold of consciousness.” This is when I like to go for a walk. I like to lay things aside, clear my head, and let my mind wander. It’s a haphazard process — sometimes nothing happens. Sometimes I simply forget what I was thinking about. Other times, however, something bubbles up that’s worth capturing. (One of the reasons I write this blog is to double back on my own thinking, recall what I wrote months ago, and perhaps make connections I would otherwise miss).

Third, is the insight — the Aha moment. As we saw in the article on sleepiness and creativity (click here), focusing intently on the problem at hand may actually inhibit the Aha experience. When you focus, you block out random thoughts and stray ideas. But it’s those very thoughts and ideas that may produce the insight. When you’re tired — or when you can induce your mind to wander — those stray thoughts are not blocked out and can help you see things more creatively.

Fourth is evaluation, “…when the person must decide whether the insight is valuable and worth pursuing.” This is a difficult step. You think you’ve had a brilliant flash of insight … you start dreaming of a trip to Stockholm to accept a Nobel Prize. On the other hand, maybe it’s just a crackpot idea that your colleagues will laugh at. A thorough understanding of the current paradigm will help. If you’re a master of your discipline, you’ll have a much better idea of which ideas are worth pursuing and which are just goofy.

The fifth step is elaboration. You develop the idea, conduct the research, test your hypotheses, and present your conclusions to your colleagues — who may just rip it apart. As Csikszentmihalyi notes, “This is what Edison was referring to when he said that creativity consists of 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration.”

Does the five-step process always produce creative innovations? No, not at all. But, if your purpose is to create new ideas, products, and services you should always be cognizant of where you are in the process. Following the process doesn’t guarantee success. But not following it virtually guarantees failure.

You can find Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s book here. Thomas Kuhn’s book is here.

Innovation: Making the Connection

Anybody want to connect?

Making connections is the basis of creativity and innovation. It’s very rare that somebody comes up with a full-blown idea on their own. Instead, they master a domain and then extend it. They learn a paradigm and then change it. They make the connection between this idea and that one. They put two and two together.

So, how do you actually make connections? I think of it as a three-level problem. First, we make new connections within our own brains. Second, we connect with other people who are more or less like us. Third, we need to expand our horizons and connect with people who aren’t like us. Here are some practical tips for each level.

In our own brains — as numerous authors have pointed out, the brain is plastic. It can change itself and enrich itself even after it stops growing. Can we teach our brains to make new connections? You betcha:

- Read things (or watch things) that you disagree with. If you only read authors who agree with your political or philosophical bent, you’re only reinforcing existing connections. Reading authors you disagree with will help you establish new connections.

- Use you non-dominant hand more often — connect to your “other” side.

- Study a foreign language — we think with words. Learn some new words and you’ll learn to think differently.

- Play games that exercise your brain — try bridge or crossword puzzles or sudoku. They all require you to see things differently and remember things accurately.

Other people like us — let’s take the context of a company’s headquarters building. How do you build connections between employees? We’re all familiar with team-building exercises. Let’s look at a few less obvious ways to connect:

- Reduce the number of coffee stations — get people to congregate at central locations. As they bump into each other, they’ll talk to each other, too.

- Reduce the number of bathrooms — same idea, get people to congregate in central locations.

- Design physical spaces that get people to carom off each other — look at the old Bell Labs architecture. Long, narrow hallways with offices arrayed along them. Step out of your office and you’re on a highway full of people. It’s hard not to bump into somebody.

- Book clubs — sponsor a book of the month club for all employees. Hint: don’t just do business books. Range farther afield into history, sociology, fiction, and so on.

Other people not like us — who is not like us? Well, if I’m in the accounting department, then sales people are not like me. Making connections with sales people might just lead to great new ideas. I see a lot of team building within departments (a team retreat for the marketing department, for instance) but not so much between departments. Here are a few ideas:

- Random seating — why is it important for accountants to sit with accountants and engineers to sit with engineers? Randomize things so that people sit by people who are different.

- Onboarding programs — help new employees make contacts across the company; not just in their own department. Early connections last a long time.

- Team building with other departments — emphasize collaboration rather than competitions. Form coss-departmental teams or go on retreats together. Get people to know each other.

- Travel more — face-to-face meetings are the best way to get to know people, especially people who are different from you.

- Connect with customers — develop programs that require your employees to work with your customers. Make the effort to bridge the gap.