Rats, Lice, and Innovation

A fundamental driver of history

I took a lot of history courses in college. Most of them were focused on a particular geography at a particular time like, say, Latin America in the 19th century.

A few, however, sought to describe and explain the entire arc of history – the grand narrative of the really big picture. I especially remember reading Arnold Toynbee’s A Study of History, a 12-volume set that chronicled 26 different civilizations and offered a cohesive explanation of why they rose and fell. (Truth be told, I read the abridged version).

As I read Toynbee, I finally came to understand the entire ebb and flow of history – why things happened and how one thing led to another. Then I read another book that shook my confidence and taught me that I probably didn’t understand much at all.

The book was Rats, Lice and History by Hans Zinsser. It’s a much more modest book than Toynbee’s but perhaps more enlightening. Its basic thesis is simple: a lot of stuff happens by accident and stupidity. One army defeats another not because of the grand arc of history but because rats have eaten the losing army’s grain. A civilization falls not because of religion (or lack of it) but because lice have spread disease among the population.

I’ve always taken Zinsser’s book as a cautionary tale. Whenever I read a grand narrative that claims to explain it all, I wonder if the author didn’t miss something random and elemental. Was Karl Marx right about the rise of the working class or did he just miss the fact that plague destroyed prevailing social structures? Did America become a great power because of Manifest Destiny or because two great oceans protected us from pathogens?

Though I understand something about pathogens, I never connected them to innovation – until last week. That’s when I stumbled across an article by Damian Murray in The Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. Murray connects pathogens to a culture’s ability to generate scientific and technical innovations.

The path from pathogen to innovation (or lack of it) is a bit circuitous. The basic argument is that the presence of pathogens causes cultures to adopt certain practices and behaviors that suppress disease. These practices include “xenophobia and prejudiced responses to foreign individuals”, the adoption of “conformist attitudes and behaviors”, traditionalism, collectivism, and authoritarianism.

Murray (and many others before him) argues that xenophobia, conformism, traditionalism, collectivism, and authoritarianism “serve to buffer against disease transmission.” In other words, they’re good for you and your culture. While these behaviors help ward off diseases, Murray argues that they also have a hidden cost: reduced ability to innovate.

These variables are linked in multiple ways. For instance, xenophobia, conformism, and traditionalism tend to produce collectivist as opposed to individualist cultures. Murray notes that a number of researchers (including Hofstede) have connected individualism to innovation. Similarly, conformism may lead to authoritarianism (or is it the other way round?) which may lead to a reduced rate of innovation.

Murray’s argument is ingenious and intriguing. But, for me, it’s not just about innovation. It illustrates a much bigger problem in understanding reality: we often don’t know what causes what. We look at the past and build arguments that A leads to B and B leads to C. Our stories are logical and comforting but probably wrong.

The French philosopher Henri Bergson warned us to beware of the “retrospective illusion”: that mechanistic forces predetermined every event in history. That history could not have happened any other way. (This feels similar to the illusion of explanatory depth). For me, Murray and Bergson are saying the same thing: don’t assume that A causes B just because it seems logical and intuitive. Maybe it was just the rats.

Success and Serendipity

Anything could happen.

Carl von Clausewitz, the renowned German military strategist, wrote that “No campaign plan survives first contact with the enemy.” It’s good to plan, organize, and coordinate but remember that the enemy will always do something unexpected. Resilience – the ability to react to new realities and change direction as needed – is probably the single most important variable in battlefield success.

Clausewitz, of course, was focused on war planning. At the risk of being presumptuous, I’d like to paraphrase the thought: No business plan survives first contact with reality. As in warfare, it’s good to plan ahead. But don’t stick to the plan blindly. Be observant and pragmatic. As you learn more about reality, adjust the plan accordingly and do it quickly.

We all like to make predictions, of course, but reality intervenes. Odd things happen. Weird coincidences occur. As we learned a few weeks ago, we all confabulate. We make up stories to explain what happened in the past. By understanding the past, we should be able to control the future.

Unfortunately, the stories we confabulate about the past are never completely true. Too many things happen serendipitously. We may think that X caused Y but reality is much more complicated and counter-intuitive. Another German, Georg W.F. Hegel probably said it best: “History teaches us nothing except that it teaches us nothing.”

If we can’t predict the future, why bother to write a business plan at all? Because it’s useful to lay out all the variables, understand how they inter-relate, and tell a story about the future. Once you have a story, you can adjust it. You can tell how closely your thinking relates to reality and change your plans accordingly. It’s like tailoring a new set of clothes. Following a pattern will get you close to a good fit. But you’ll need several fittings – a nip here, a tuck there – to make the ensemble fit perfectly.

This approach to planning also emphasizes the importance of serendipity. My favorite definition of serendipity is “…an aptitude for making desirable discoveries by accident.” If you could predict the future accurately, you wouldn’t need serendipity – you would simply follow the plan. Since you can’t predict the future, you need to promote serendipity as part of your plan.

How do you promote serendipity? The simple answer is that you do new things. Talk to different people. Take a different route to work. Study a new language. Travel to a new country. Take a course in a new discipline. Don’t ever assume that you know what you’re doing. Remember what Louis Pasteur said, “Chance favors the prepared mind.” Never let an accident go to waste.

Social Media and Empty Calories

I’m at my bliss point.

Can’t stop eating those potato chips? Blame it on the bliss point.

On a graph, the bliss point looks like an upside-down U. Think of it as a crave curve. At the top of the curve, the food you’re eating provides maximum bliss and minimum warning. You crave it and simply want more. If you move past the top of the curve, however, the food starts to alert your brain that you’ve eaten enough. You stop eating.

Being good marketers, food engineers want you to eat more. They aim to hit the top of the crave curve. As it happens, “…big, distinct flavors [tend] to overwhelm the brain, which responds by depressing your desire to have more.” So food engineers blend flavors to get just the right bliss balance that will keep you consuming.

As with food, so with slot machines. As the anthropologist Natasha Dow Schüll points out, slot machine designers aim for a mechanical version of the bliss point called the “machine zone”.

Once players enter the machine zone, their “…worries, social demands, and even bodily awareness fade away. … gambling addicts play not to win but simply to keep playing as long as possible….” Like food engineering, game engineering aims to keep you going … just one more nibble or one more pull on the slot machine’s arm.

I wonder if social media doesn’t work the same way. It’s simple, it’s repetitive, and it’s enjoyable. Just one more peek … it’s an innocent pastime, isn’t it? It can’t really hurt anything, can it?

I took a short break just a moment ago and checked my social media. What did I learn? Well, I found out what a former colleague had for lunch today in Minneapolis. Did I really want to know that? No … but think of what I might have learned. I might have found that several people “liked” my latest article. I might have learned that a professional association wants to hire me for a keynote speech. I might have discovered that Tilda Swinton wants to invite me to lunch. Oh, the possibilities.

There’s an old joke that second marriages are the triumph of hope over knowledge. The same is true for social media. The reality is that most of what we discover on social media is rather boring. But maybe … just maybe … something interesting has happened. We have to check. It’s like being in the machine zone. Our worries and social obligations just fade away.

And when something interesting does happen, we get a little reward, just like a slot machine. In reality, the reward never equals the investment. But, as we bask in the glow of the reward, we forget that. We’re in the zone. We can’t break away. In fact, we don’t even want to break away.

My Mom used to say that it’s easier to avoid temptation than to resist it. I’ve learned not to stock potato chips in the house. I’ve learned not to frequent gaming dens. Maybe it’s time to put the social media away, too.

Sitting Still In a Room

Sit still!

In the late 1650s, the French mathematician and philosopher, Blaise Pascal, wrote an insightful sentence, “All of man’s problems stem from his inability to sit still in a room.”

Collected in Pascal’s unfinished Pensées, this little tweet from the 17th century has enlightened us for 350 years. In fact, it has recently received new impetus and momentum from an article in Science magazine.

Titled “Just think: The challenges of the disengaged mind”, the article reports on 11 different studies. Taken together, they show that people – and men especially – would rather receive electric shocks than sit alone in a room.

The article looks at default mode processing and asks two simple questions: “Do people choose to put themselves in default mode by disengaging with the external world? And when they are in this mode, is it a pleasing experience?” As the authors note, we might assume that it’s easier to guide our thoughts in “pleasant directions” when we disengage with the world. However, that’s not what they found.

To study these questions, the researchers asked students to sit still and alone in various locations (a research lab, a dorm room, etc.). They were simply asked to “entertain themselves with their thoughts….” After sitting still for six to 15 minutes, the students reported that it was hard to concentrate, their minds wandered, and, by and large, they didn’t enjoy the experience.

Maybe it’s just college students. But the researchers repeated the studies with people recruited from local churches and at a local farmer’s market. The results were quite similar. Indeed, the researchers found no evidence that demographic factors – gender, age, income, education, etc. – were producing the results. It seems that people from all walks of life just don’t like to sit alone and think.

The researchers then asked another question: “Would [the participants] rather do an unpleasant activity than no activity at all?” Was it just the sitting still that made people stir crazy? The researchers told participants that, instead of just sitting still, they could press a button and receive an electric shock.

With the electric shock in place, the results differed significantly by gender. Two-thirds of the men gave themselves at least one electric shock; only one-fourth of the women did. In other words, a majority of men seem to prefer pain over thought.

That’s not encouraging. I’ve always had faith in reason. I believe that, with patience and goodwill, we should be able to reason our way through our problems. But, as the researchers point out, our “… minds are difficult to control…and it may be particularly hard to steer our thoughts in pleasant directions and keep them there.”

Perhaps meditation training would help. Perhaps we can learn to manage our thoughts and enjoy the process of thinking. Ultimately, however, the researchers conclude that, “The untutored mind does not like to be alone with itself.” That’s just what Pascal said. We haven’t made much progress in 350 years.

Crosswords, Wu-Wei, and Flow

Five letters …Chinese system of thought

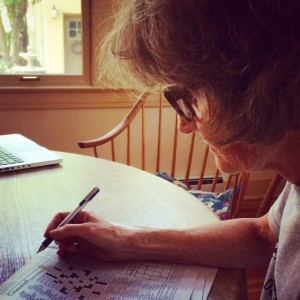

Suellen and I like to do crossword puzzles together. We enjoy sorting out the wordplay and ambiguities and finding the solution. When we can’t figure out the answer, we use the same strategy but different tactics.

Our strategy might be called indirection – we move away. I’ve discovered that I often find the answer when I give up. I look at Clue #3 and can’t figure it out. So I think, “Well, I can’t get it so I might as well move on to Clue #4.” In the very brief time that it takes me to move from Clue #3 to Clue #4, the answer often comes to me. I’ve de-focused and given up when the answer simply pops into my head.

Suellen’s indirection is physical and spatial rather than temporal. We typically work at a table and we usually lean in close to the puzzle. When Suellen can’t get the answer, she stands up and looks at the entire puzzle from a distance. She sees the puzzle as a whole and spots patterns. Capturing the global nature of the puzzle helps her sort out specific clues.

In both cases, we move away. We’re no longer trying to solve a specific clue. We’re not doing rather than doing. I thought of this when I read “Trying Not To Try” by Edward Slingerland in a recent issue of Nautilus. Slingerland is a professor of Asian studies and cognition (what a great combo) at the University of British Columbia.

Slingerland describes the Daoist concept of wu-wei or effortless action. “Wu-wei literally translates as ‘no trying’ or ‘no doing’ but it’s not all about dull inaction. In fact, it refers to the dynamic, spontaneous, and unselfconscious state of mind of a person who is optimally active and effective.”

Slingerland argues that achieving wu-wei requires us to balance and integrate Systems 1 and 2. As you may recall, System 1 is our low-energy thinking system that is fast, automatic, effortless, and always on. System 1 makes the great majority of our decisions automatically — we don’t need to think about them. System 2 is the conscious energy hog that helps us think logically and provides executive task control. When we say, “I gave myself permission to have another glass of wine”, we’re essentially saying, “My System 2 gave my System 1 permission…”

Wu-wei integrates the two systems. Slingerland writes, “We have been taught to believe that the best way to achieve our goals is to reason about them carefully and strive consciously to reach them. But [wu-wei] … shows us that many desirable states are best pursued indirectly. … When your conscious mind lets go, your body can take over.”

Wu-wei also reminds me of the concept of flow described by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. For instance, Csikszentmihalyi writes that flow involves a stage called incubation, “…during which ideas churn around below the threshold of consciousness.” Similarly, there is an insight phase – an Aha moment. At this stage, too much focus can be self-defeating. You need to let your mind wander. You need to not try too hard.

Whether we call it wu-wei or flow or something else, it’s a remarkable concept. Trying not to try may seem contradictory but it’s worth a try. I find that taking a good long walk can help me get nearly the right balance. My body is occupied and my mind wanders. I’m not trying to do much of anything. That’s when the insights come.