Rats, Lice, and Innovation

A fundamental driver of history

I took a lot of history courses in college. Most of them were focused on a particular geography at a particular time like, say, Latin America in the 19th century.

A few, however, sought to describe and explain the entire arc of history – the grand narrative of the really big picture. I especially remember reading Arnold Toynbee’s A Study of History, a 12-volume set that chronicled 26 different civilizations and offered a cohesive explanation of why they rose and fell. (Truth be told, I read the abridged version).

As I read Toynbee, I finally came to understand the entire ebb and flow of history – why things happened and how one thing led to another. Then I read another book that shook my confidence and taught me that I probably didn’t understand much at all.

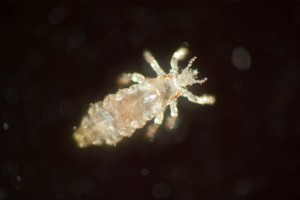

The book was Rats, Lice and History by Hans Zinsser. It’s a much more modest book than Toynbee’s but perhaps more enlightening. Its basic thesis is simple: a lot of stuff happens by accident and stupidity. One army defeats another not because of the grand arc of history but because rats have eaten the losing army’s grain. A civilization falls not because of religion (or lack of it) but because lice have spread disease among the population.

I’ve always taken Zinsser’s book as a cautionary tale. Whenever I read a grand narrative that claims to explain it all, I wonder if the author didn’t miss something random and elemental. Was Karl Marx right about the rise of the working class or did he just miss the fact that plague destroyed prevailing social structures? Did America become a great power because of Manifest Destiny or because two great oceans protected us from pathogens?

Though I understand something about pathogens, I never connected them to innovation – until last week. That’s when I stumbled across an article by Damian Murray in The Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. Murray connects pathogens to a culture’s ability to generate scientific and technical innovations.

The path from pathogen to innovation (or lack of it) is a bit circuitous. The basic argument is that the presence of pathogens causes cultures to adopt certain practices and behaviors that suppress disease. These practices include “xenophobia and prejudiced responses to foreign individuals”, the adoption of “conformist attitudes and behaviors”, traditionalism, collectivism, and authoritarianism.

Murray (and many others before him) argues that xenophobia, conformism, traditionalism, collectivism, and authoritarianism “serve to buffer against disease transmission.” In other words, they’re good for you and your culture. While these behaviors help ward off diseases, Murray argues that they also have a hidden cost: reduced ability to innovate.

These variables are linked in multiple ways. For instance, xenophobia, conformism, and traditionalism tend to produce collectivist as opposed to individualist cultures. Murray notes that a number of researchers (including Hofstede) have connected individualism to innovation. Similarly, conformism may lead to authoritarianism (or is it the other way round?) which may lead to a reduced rate of innovation.

Murray’s argument is ingenious and intriguing. But, for me, it’s not just about innovation. It illustrates a much bigger problem in understanding reality: we often don’t know what causes what. We look at the past and build arguments that A leads to B and B leads to C. Our stories are logical and comforting but probably wrong.

The French philosopher Henri Bergson warned us to beware of the “retrospective illusion”: that mechanistic forces predetermined every event in history. That history could not have happened any other way. (This feels similar to the illusion of explanatory depth). For me, Murray and Bergson are saying the same thing: don’t assume that A causes B just because it seems logical and intuitive. Maybe it was just the rats.

One Response to Rats, Lice, and Innovation

-

Pingback: My iPod Is Conscious | Travis White Communications