Corporate Culture: Counting The Uncountable

You can’t measure love.

I was in a meeting not long ago with a client whose organization is undergoing a significant transformation. We were discussing what needed to change and how we might promote the appropriate change efforts. A senior executive spoke up to say, “Well, you get what you measure.” Nobody challenged the assumption behind the thought and we began to focus on how to measure change in the organization.

I had, of course, heard similar statements many times before. Business schools emphasize measurement as a key ingredient of management. As a leader, you point the way, establish some key measurements, and then harvest the results. Sounds simple, doesn’t it?

But think about the things that we don’t bother to measure – or that we don’t know how to measure. These include love, respect, hope, initiative, creativity, open-mindedness, ability to resolve conflicts, receptiveness to new ideas, focus, drive, and resilience. Do we really not care about these things?

We tell managers that the most important thing they can do is build a positive, engaging organizational culture. (See here and here). We also tell them they can only get what they measure. Yet many of the components of culture are simply not measureable. I have yet to hear a manager say, “In the third quarter, we increased corporate resilience by 3.2% compared with the same quarter in the previous year.”

So, how do we help managers build a positive culture even when they can’t measure it? Here are some thoughts:

- The answer is not a number on a piece of paper. It’s OK to look at numbers but we need to remember that a number is an abstraction of a measurement that is an abstraction of reality. Looking only at numbers is like driving your car by looking only at the speedometer.

- Trust is an unrecognized but important ingredient. We focus on measurement partially because we don’t trust our eyes, and ears, and subordinates. A measurement is supposed to give us an “objective” view of the organization. But a measurement is only as objective as the person taking the measurement – which is to say, not very. If we can create a culture built on trust, we can learn more about our organization than a measurement will ever tell us. (In this regard, it’s useful to review Edwards Deming’s 14 points of management and his red bead experiment).

- Learning to observe is more important than learning to measure. We forget that measurement is just one form of observation. Management by walking around still works. Taking groups of employees out to dinner will teach you more than a spreadsheet will. Practice being naïve – ask questions that a rookie would ask. You may think you don’t need to ask certain questions because you already know the answer. But you’re probably wrong.

- A good conversation is more important than a staff meeting. Staff meetings can be useful but they’re also very structured. You get the information that the structure permits. A good conversation is much more open-ended. You can wander about until you touch on the really important issues.

- Questions are more important than answers. A number from a measurement purports to give us an answer. But it only answers the question you asked – and the answer may not be accurate. Learn how to ask probing questions that get rich and unexpected answers. Tip: a good course on critical thinking will help.

I think we obsess about measurement because we have a bad case of physics envy. We want our organization to behave like a physics experiment. If we apply Force X, we get Result Y. It doesn’t work that way and never will. Time to get over the measurement mania.

Is Critical Thinking The Ultimate Job Skill?

Interesting syllogism. But the premise is unsound. That’s why I get the big bucks.

When I went off to college, my mother told me, “Now remember … you’re going to college to learn how to think. Don’t miss that lesson.”

I wonder what she would say if she were sending me off to college today. It might be more along the lines of, “Now remember … you’re going to college to get a good job. Don’t blow it.”

We can only judge programs and processes based on their goals. If the goal of government is to provide good services at a reasonable cost, we might give it a fairly low grade. However, if the goal of government is to increase employment, then we might evaluate it more positively. The same is true of higher education. So what is the goal of higher education? Is it to teach students how to think? Or is it to provide them skills to get a job?

I would argue that the goal of higher education – indeed of any education – is to improve the students’ ability to think. Good thinking can certainly help you get a job. In fact, it may be the ultimate job skill. But good thinking can take you much farther than a good job. Here’s my thinking on the issue:

1) Thinking is foundational — the essence of running a business (or a government) is to make decisions about the future. To make effective decisions, we need to understand how we think, how our thinking can be biased, and how to evaluate evidence and arguments. If we know everything about finance, for instance, but don’t know how to think effectively, we will make decisions based on faulty evidence, weak arguments, and unconscious biases. By chance, we might still make some good decisions. But we should remember Louis Pasteur’s thought, “Chance favors the prepared mind.”

2) The future is unknowable — our niece, Amelia, will graduate from college next May. If she works until she’s 65, she’ll retire in the year 2060. What skills will employers need in 2060? Who knows? As I reflect on my own education, the content I learned in college is largely useless today. The processes I learned, however, are still very relevant. Thinking is the ultimate process. Amelia will still need to think effectively in 2060.

3) Thinking promotes freedom – if we can’t think for ourselves, we will forever be buffeted by other people’s agendas, desires, ambitions, and rhetorical excesses. Critical thinking allows us to assess ideas and social movements and make effective decisions on our own. We can frame our thinking as we wish and not allow others to create frames for us. We can identify the truth rather than relying on others to tell us what is true. Critical thinking, allows us to take control of our own destiny, which is the essence of freedom. I don’t know of any other discipline that can make the same claim.

The Art Of Transformation

What’s the difference between an art and a craft?

What’s the difference between an art and a craft?

A traditional definition focuses on differences in expectations and outcomes. With a craft, we know precisely what the outcome will be, even before we start. We have a set of instructions and, if followed faithfully, the outcome is guaranteed.

By contrast, an artist doesn’t know what the outcome will be. Creating an artwork involves exploration, doubt, questioning, trial-and-error, and no small amount of anxiety. An artist explores the unknown and aims to give us new insights. A good artwork may not be beautiful in a classic sense, but it is always imaginative. A craftsman, on the other hand, creates the expected and delivers beauty and pleasure through execution more than imagination.

I thought of these distinctions the other day when I toured a major new exhibition, Women of Abstract Expressionism*, at the Denver Art Museum. The exhibition highlights a dozen leaders of the abstract expressionist movement and their work from roughly 1945 to 1960. Here’s how two of the artists describe the creative process:

- Grace Hartigan: “Eventually, the painting tells you what it wants to be.”

- Jay DeFeo: “When I start, I don’t know what’s going to happen. When you’re dancing, you don’t stop to think: now I’ll take a step … you allow it to flow.”

It occurs to me that the distinction between art and craft also applies to organizational development. Change management is a craft. Organizational transformation is an art.

We often invoke change management when we begin a concise and well-delineated project. We understand the boundaries and the players. We move through well-defined phases that we can measure objectively. We expect changes to occur between people – perhaps with new reporting structures and alignments. Change management is not easy to master but it seems to me that it is a craft. We often celebrate the end result. We can do that precisely because it is a craft – we know when the process ends.

Organizational transformation is much more like an art. When we seek to transform an organization’s culture, we have only a fuzzy idea of where we’re going. Milestones exist but they’re not well defined. Transformation requires changes within people rather than only between people. We can’t see those changes; nor can we measure them. If we try to measure the unmeasurable, we’ll go off course. Like any other art, transformation involves exploration, doubt, questioning, trial-and-error, and no small amount of anxiety. Paraphrasing Grace Hartigan, “Eventually, the organization tells you what it wants to be.” The secret to success is listening, not measuring.

I sometimes ask my artist friends how they know when a piece they’re working on is finished. None of them has very good answers. Some say they “just know”. Others say that they just get tired of it. Others say that it’s never finished. Whenever they see it again, they’re tempted to make “just a few minor changes.”

It occurs to me that I’ve never been to a party to celebrate an organizational transformation. Perhaps it’s because we just don’t know when the transformation is finished. It’s an art not a craft.

*The Women of Abstract Expressionism exhibit is both superb and unexpected. The paintings are exciting and energetic. The painters are almost anonymous. This is the first major exhibition – anywhere in the world — of the women who energized the abstract expressionist movement. That it happened in my hometown makes me more than just a little bit proud. You can see it – and should see it — until September 25th.

The painting illustrating this article is Grace Hartigan’s The King Is Dead, from 1960.

Do Nudges Work? Should We Use Them?

It’s for your own good.

Ever since Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein published Nudge in 2008, we’ve been debating the ethics and practicality of “nudging” people into making the “right” decisions.

Thaler and Sunstein mine the same intellectual vein worked by Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, Dan Ariely, and Charles Duhigg. We may think we make rational decisions but we have biases, habits, and quirks that inject a degree of irrationality into every decision we make. While the other researchers explain how our heuristics work, Thaler and Sunstein give practical advice for nudging people toward rational decisions that serve their best interests.

Thaler and Sunstein refer to their work as “libertarian paternalism”. It sounds like an oxymoron but the basic idea is that you still have the right to screw up your life by making bad decisions. At the same time, we (whoever “we” is) will nudge you into making decisions that are good for you.

Most observers seem to have accepted that nudging by the government or by your employer is ethically acceptable. After all, it’s good for you, right? But there is a minority that objects to the paternalism inherent in the concept. For instance, Michael Beran writes that, “The authors of Nudge seem not to understand that the welfare of a people depends in part on their being free to choose badly. … Probably most people … can point to experiences where their mistakes proved fruitful. … Should we gradually foreclose the freedom to be stupid, we will almost certainly end up being less intelligent.”

So is nudging libertarian paternalism, as Thaler and Sunstein would have it or false benevolence, as Beran would put it? It seems like a debate that’s worth having … but not before we answer a more basic question: does nudging work? Why bother to debate the ethics of a concept if it doesn’t actually work?

So, does nudging work? We have a lot of anecdotal evidence that making one choice easier than another can nudge people in the “right” direction. For instance, if we want to encourage organ donations, we can offer people a choice to donate or not when they get their driver’s license. The driver’s bureau can structure the default option in one of two ways: 1) You’re not a donor unless you opt in; 2) You are a donor unless you opt out. It seems likely that Option 2 would nudge people in the right direction.

As we know, however, anecdotal evidence is very weak. We tend to make up stories that fit our preconceived notions. And Frank Pasquale, writing in The Atlantic, argues that nudges are often too weak to overcome ingrained behaviors. So, is there any controlled, randomized research that would answer a simple question: does nudging work?

Somewhat surprisingly, the first such research was published just last month in Science magazine. (Click here). John Bohannon, the article’s author, reports on 15 controlled trials that involved more than 100,000 people in the United States. The trials involved signing up for various government-supplied social services. In each case, some randomly selected participants were given the “standard application.” Other participants were given a “psychological nudge in which the information was presented slightly differently … for instance, … one choice was made easier than another.”

The results? “In 11 of the trials, the nudge modestly increased a person’s response rate or influenced them to make financially smarter decision.” Bohannon includes data on three of the trials, which moved decisions in the right direction by 2.9%, 3.6%, and 11%. As Bohannon notes, these are modest changes but the costs were probably low as well (no data were given on costs). If so, the cost-benefit may be positive as well.

We now have some solid evidence that nudges actually work. We don’t know the cost-benefit ratios but let’s assume for a moment that they’re positive. If so, the question becomes, should we encourage the government to use them? On the one hand, as Bohannon notes, businesses pay billions of dollars per year for their own nudges, known as advertising. Why shouldn’t the government participate on (closer to) equal footing? On the other hand, libertarians argue that it’s really another kind of nudge – toward the nanny state. I’ll write more about the debate in the future. In the meantime, what do you think?

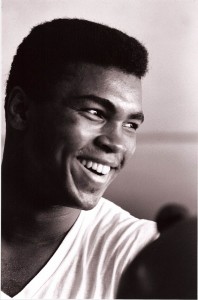

When I Met Muhammad Ali

The smile.

In 1968 or 69, when I worked on the student newspaper at the University of Delaware (UD), I drew an assignment to interview Muhammad Ali. I was a fairly random choice since I didn’t cover sports. But the angle of the story was Viet Nam and the antiwar movement. Since I wrote about politics, I volunteered eagerly to meet the man behind the legend.

At the time, Ali was in his three-and-a-half year exile from boxing. In 1967, Ali had refused to be drafted in the army and filed for conscientious objector status. He also made the memorable statement, “I ain’t got no quarrel with the Viet Cong. No Viet Cong ever called me nigger.” His political positions coupled with his fame made him one of the most polarizing figures of American history. Boxing commissions stripped him of his title and no state would grant him a license to fight. (The Supreme Court later unanimously granted him conscientious objector status and he resumed his boxing career).

My assignment was straightforward. Ali was on a speaking tour of college campuses and was preparing to give a speech at Delaware State University. I was to drive to DSU and, with a dozen or so other journalists, spend an hour interviewing him. The fact that Ali was speaking at DSU, instead of UD, was telling. Though the state of Delaware was a not “southern”, its educational system was highly segregated. The University of Delaware was for white students; Delaware State was for black students. Indeed, Delaware State was founded in 1891 as the State College for Colored Students. Perhaps for obvious reasons, Ali chose to speak at Delaware State.

Ali was a member of the Nation of Islam, often referred to as Black Muslims. (He later converted to mainstream Islam). At the time, the Nation of Islam advocated the separation of races and viewed “white devils” as an inferior race created by an evil scientist. On judgment day, white people would be destroyed.

I had followed Ali’s career closely and knew something about his strength and speed. It’s a little known fact that I boxed in the Golden Glove preliminaries in high school. I wanted to box like Ali. I knew that we were both the same height – 6 foot 3. His reach was 78 inches. So was mine. He was fast. So was I. The difference: he weighed 215 pounds and was athletic. I weighed 160 pounds and was nerdy. I could float like a butterfly but my sting was like a damp Kleenex.

I found my way to the right building on the Delaware Sate campus. The meeting room was just down the hall and around the corner. I rounded the corner and practically tripped over Muhammad Ali.

I wasn’t prepared and didn’t know what to expect. I was eager to meet him but also nervous. He was the most famous person I ever met (still true today). But perhaps he wouldn’t be happy to see me. Perhaps he would deem me a white devil and ban me from his presence. But, in fact, he was one of the most gracious people I have ever met. I was stammering awkwardly and he had no particular reason to be nice to me but he welcomed me warmly and offered me a hand that seemed twice as large as mine.

Since we were the same height, I assumed that I could look him in the eye. But no – he seemed so much bigger than I was. I don’t know where charisma comes from but he had it in vast quantities. He was far more charismatic than Bill Clinton, whom I met many years later. Ali seemed to float in the air in front of me.

I’ve just read several obituaries of Muhammad Ali. They discuss his athletic prowess, his political views, his religious development, and, course, his verbal jousting. What I saw was a thoughtful, caring, magnetic individual who invited me into his world for about an hour.

During the press round table, I know I asked some questions, but I don’t remember them. I know I wrote an article, but I don’t remember it. What the obituaries don’t mention was his smile. It was magnanimous and all encompassing. That’s what I’ll remember.