Innovation and Diversity

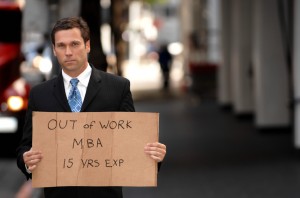

Do you have an MBA? So do most of the people I work with at my client organizations. One of the ways I add value is merely by the fact that I don’t have an MBA.

It’s not that having an MBA is a bad thing. It’s that so many companies are run by people educated in the same way — they all have MBAs. The fact that I don’t have an MBA doesn’t mean that I think better than they do. But I do think differently. Sometimes that creates problems. Oftentimes, it creates opportunity.

If all your employees think alike, then you limit your opportunity to be creative. Creativity comes from connections. By connecting concepts or ideas in different ways, you can create something entirely new. This works at an individual level as well as an organizational level. If you read only things that you agree with, you merely reinforce existing connections. If you read things that you disagree with, you’ll create new connections. That’s good for your mental health. It’s also good for your creativity.

At the organizational level, connecting new concepts can lead to important innovations. Indeed, the ability to innovate is the strongest argument I know for diversity in the workforce. If you bring together people with different backgrounds and help them form teams, interesting things start to happen.

In this sense, “diversity” includes ethnic, economic, and cultural diversity. It especially includes academic diversity. As a leader, you want your engineers, say, to mix and mingle with your humanities graduates. Perhaps your lit majors could improve your MBAs’ communication skills. Perhaps your philosophers can help you see things in an entirely new light. In today’s world, innovation requires that you bring together insights from multiple disciplines to “mash up” ideas and create new ways of seeing and doing.

Most companies keep data on ethnic diversity within their workforce. However, they don’t usually keep statistics on the different academic specialties represented among their employees. You may well have enough MBAs. But do you have enough linguists? Philosophers? Sociologists? Anthropologists? Artists? If not, it’s time to start recruiting. The result could well be a healthier, more innovative company.

Metaphors: What Companies Really Believe

Most companies pay a lot of attention to their formal messages. They’ll work for hours writing and re-writing slogans. They’ll spend days trying to perfect their mission statement. They’ll work hard to get their press release just right.

Metaphors, on the other hand, attract very little formal attention or review. Ask an employee what it’s like to work for a company and they’ll often use metaphors in their response. These metaphors typically are not carefully crafted. They occur naturally, without forethought or guile. Precisely for this reason, they provide an excellent window into what the company really thinks.

If you’re thinking of buying from or working for a company, pay particular attention to the metaphors that employees use. The metaphors will give you insights into the company that you’ll never glean from the formal messages.

If you’re an executive of the company, you also need to pay attention. Your employees may use metaphors that undercut the company’s position. Worse, they may have acquired those metaphors from you. Listen to the metaphors and decide whether you need to change them. If you do, you’ll need some new stories.

Learn more in the video.

Moderating the Extremes

Your friend, Mary, avidly and vocally supports a national flat tax. Or maybe she’s convinced that free trade is the only sensible way to stimulate the world economy. Or maybe she actively supports more government programs to ensure equality of opportunity.

Let’s also assume that you disagree with Mary. You’d like her to see your side. But she’s so convinced that she’s right — and everybody else is wrong — that it’s difficult to have a conversation with her. Your attempts at dialogue just devolve into long-winded diatribes.

So how do you move Mary? Here are two different communication strategies:

- Ask Mary why she thinks her position is correct.

- Ask Mary how her ideas would work in the real world.

If you pursue Strategy 1, Mary will simply launch into her “pre-recorded” sound bites and positions. Strategy 1 does not require Mary to think. It merely requires her to repeat. She continues to convince herself. As a result, Mary’s position will likely become even more extreme.

Strategy 2, on the other hand, requires Mary to think through a variety of complicated, real-world issues. A common feature of extreme political positions is that they’re over-simplified. By requiring Mary to think through complicated issues, Strategy 2 often reveals weaknesses in the logic. It’s not so simple as it seemed. As a result, Mary’s position often becomes more moderate and more nuanced.

The effectiveness of Strategy 2 derives from the “illusion of explanatory depth”. In their article on the phenomenon (click here), Leonid Rozenblit and Frank Keil explain that, “People feel they understand complex phenomena with far greater precision, coherence, and depth than they really do; they are subject to an illusion—an illusion of explanatory depth.” When you ask people how their ideas would actually work, they start to bump into the limits of their illusion. They don’t understand it nearly as well as they thought. As their explanation falters, so does the certitude of their position.

In this final week of the presidential campaign, many people are stating extreme positions. If you want to have a substantive discussion with another person — as opposed to a battle of sound bites — don’t ask why they believe something. Rather, ask them how it works.

Strip My Gears and Call Me Shiftless

I used to be proud of my ability to focus. When I was a software executive, I could identify my top priorities for the day and focus on

getting them done. That sometimes meant that I turned off my phone and ignored my e-mail. I had an assistant who could run interference for me. Sometimes, I hid in an office where my colleagues wouldn’t expect to find me. I could focus for several hours at a time — maybe even an entire day — and just get stuff done.

Now that I’m a consultant with multiple clients, I’m constantly shifting from one topic or task to another. I can’t hide from my boss to get stuff down. I am the boss. I can’t very well hide from my clients. If they can’t find me, they don’t pay me. I feel like I randomly shift from one topic to another, from one client to another, from one task to another. Like an old car, I’m worried that the constant shifting will strip my gears.

What to do? Here’s what I’ve figured out. I’d love to hear your suggestions as well.

- Multi-tasking doesn’t really work — I can’t do multiple things at the same time. I need to tuck myself away and focus on getting one thing done.

- It doesn’t much matter what you do first — when I need to do multiple tasks, I used to agonize about which one to do first. Which one would make the best use of my time? I could waste a good half hour trying to decide what to do next. Now, I just roll a dice, pick the task and get to work. Just pick one.

- Just finish one — I try very hard not to let Task B interfere with Task A before I’ve finished Task A. Shutting down a task and re-starting it both take a lot of time. It’s more efficient to just finish something.

- Don’t check messages mid-task — I like to check my e-mail. I always expect to find something exciting. Rather than checking it randomly, I’ve trained myself to check only after I’ve finished a logical task. It’s my reward.

- Have a plan, even if you can’t stick to it — I always start the day with a plan of what I want to get done. I may not be able to stick to it, but I always have a mental image of where I am compared to plan.

- Give myself little rewards — when I complete a task, I give myself a reward. That could be as simple as getting another cup of coffee or taking the dog for a walk (she always makes me happy). Knowing that a reward is coming up give me an extra incentive for finishing something.

- Say no — I do turn down clients from time to time just because I know I’ll have too much work to do. The first time I turned down a new client, it was very hard on me. Surprisingly, it gets easier.