Can Zara Stop Globalization?

For several decades, I’ve assumed that globalization is more-or-less inevitable. As communication and transportation costs decline, manufacturers find it ever easier to take advantage of lower labor costs in developing countries (a process known as labor arbitrage). But recent developments may result in a new phenomenon, often described as glocalization – a worldwide trend toward local production and consumption. Three trends stand out as especially important: fast fashion, changing labor content, and the rise of a global middle class.

Fast is fashionable – based in Galicia, Spain, Zara SA pioneered the concept of fast fashion. The idea is simple – take newly spotted fashion trends from concept to deliverable in a matter of days, rather than weeks or months. Most apparel retailers introduce four to six clothing collections per year. Zara introduces as many as 20. Such speed has propelled Inditex, the group that owns Zara, to the “world’s largest apparel retailer”.

To move quickly, Zara and other fast fashion retailers, have to shrink their supply chains. They can’t wait weeks for shipments from faraway suppliers. The retailers have come to depend on local – or even hyperlocal – suppliers.

What’s next in fast fashion? Clothing-as-a-service. Most of my readers are not clothes horses, but we all have items in our closest that we will never wear again. So, why buy when you can rent? Rent The Runway is a subscription fashion service that will happily send you the latest fashions to use for a few days. Rent The Runway is even faster than Zara and even more dependent on hyperlocal suppliers.

By themselves, Zara and Rent The Runway won’t change our global supply chains. But other manufacturers are likely to adopt their business models. The “as-a-service” model is especially attractive. Uber and Lyft provide transportation as a service. Quip provides toothbrushing as a service. Salesforce provides software as a service. Google provides email as a service. And let’s not forget that libraries provide books as a service. As the “as-a-service” model proliferates, we’ll own less and use shorter, more localized supply chains.

Changing Labor Content – labor arbitrage works best under two conditions: 1) different countries – those that supply manufactured goods and those that consume them – have widely different pay scales; 2) the item being manufactured requires a lot of labor. The second variable – labor content – has been shrinking rapidly as factory automation proliferates. Today, a fully automated factory in say, Viet Nam is not appreciably cheaper than a similar factory in say, Nebraska. Moving production offshore is less appealing when the bulk of the value in a manufactured item comes from services other than labor.

Changing labor content affects services as well as goods. Many companies, for instance, have offshored their customer call centers to take advantage of lower labor costs in other countries. But artificial intelligence and improved voice recognition may soon change the economics of such decisions. When we can talk to a robot without realizing it (which will happen soon), it makes more sense to staff call centers with robots than with low-wage foreign workers.

The Rising Global Middle Class – recent estimates suggest that some 42% of the world’s population – roughly 3.2 billion people – are now in the middle class. Global poverty is shrinking, and global buying power is increasing. This does two things: First, the wage differential between developing and developed countries is shrinking rapidly. This shifts the first variable in the labor arbitrage equation. Second, and more subtly, it shifts the demand location. More people in developing countries can now afford to buy locally produced goods and services. Rather than shipping goods overseas, local manufacturers now have a growing local market for their products.

As McKinsey and Co. point out, this trend reduces trade intensity – the proportion of goods that are produced in one country and sold in another. In 2007, for instance, China exported 17% of what it produced. By 2017, this figure declined to 9%.

What’s it all mean? Perhaps it means that our nascent trade wars are not necessary. Populist governments are trying to stop globalization through tariffs and other punitive measures. The tools are crude and outcomes uncertain. But the problem they’re trying to solve has already morphed into something different. Rather than solving yesterday’s problem through political means, it may well be better to just let the market trends play out.

The goal now is to take advantage of glocalization rather than to stop globalization. Trade intensity and labor arbitrage are both falling. We’re moving toward shorter rather than longer supply chains. Exports of manufactured goods are growing in absolute terms but shrinking relative to service exports and local consumption. We may see some decoupling of established international supply chains. Is glocalization good news? In many ways it is. The shift from global to local production will probably create local jobs and even greater personalization. As always, there are risks as well. Ed Luce, writing in the Financial Times, quotes an old saying, “When countries stop trading goods, they start trading blows.”

Whom Do You Trust? America or Facebook?

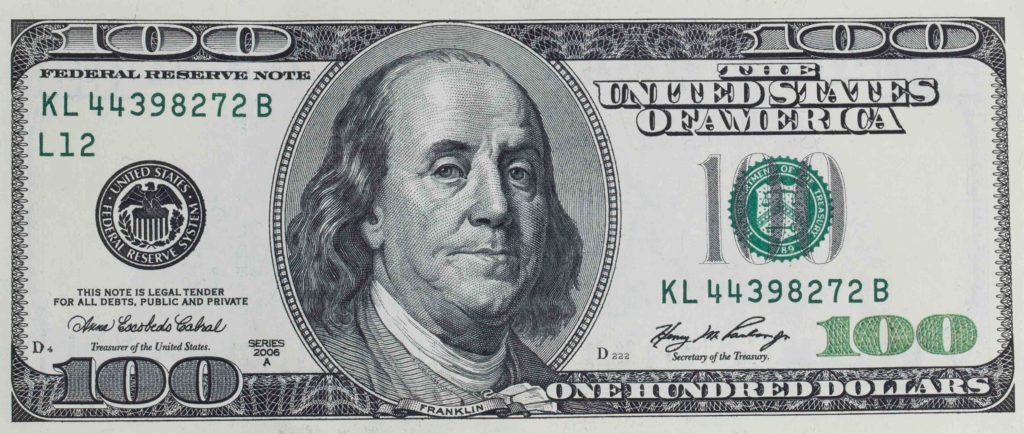

The promise of cryptocurrencies is that we can create a widely-acceptable medium of exchange without having to trust anyone. Cryptocurrencies have no central authority, no government agency to vouch for them. We don’t need to trust a government or a bank or a stock exchange. Elites can’t cheapen our currency because no elites are involved. Indeed, no one is involved. The currency is distributed across multiple computers and multiple networks. To manipulate the currency, one would need to control all the computers in the world – a seemingly impossible task.

In the original conception, the value of a cryptocurrency is based on nothing more than supply-and demand. Value is not linked to any physical asset like gold or oil or even paper currencies like dollars. Since there is no asset behind the currency, no one can manipulate the value of the currency by manipulating the underlying asset. Rather than trusting a government or an agency or a bank, we place our trust in an algorithm distributed around the world.

(The distributed nature of cryptocurrencies also makes them quite slow. Speeding up transactions is a major challenge for blockchain researchers. The most promising solution seems to be “sharding” – a technology worth keeping an eye on.)

Traditionally, we’ve trusted governments to create and maintain the value of national currencies. That’s been a pretty good bet in the United States, less so in Venezuela. But, really, do we need a nation to create a widely acceptable currency? Cryptocurrencies suggest that the answer is “no”.

But there’s a not-so-subtle problem with cryptocurrencies. The elephant in the room is that many people (myself included) view cryptocurrencies as a new version of the Wild West – a territory populated by libertarians, wild-eyed visionaries, snake oil salesmen, drug dealers, scam artists, and terrorists. And, by the way, some person created the algorithm and could potentially manipulate it for illicit purposes. Simply put, the current cryptocurrency scene does not inspire trust.

To fill the trust gap, several “trusted” agencies have stepped forward to offer cryptocurrencies based on a trusted brand and/or on physical assets. Case in point: J.P. Morgan Chase’s “JPM Coin”. Announced earlier this year, (click here, here, and here) JPM Coin is backed by a major bank and based on a physical asset: the U.S. dollar. The company touts JPM Coin as a simpler, faster way to make and clear payments.

This past week, of course, another “trusted” organization – Facebook – announced that it will introduce a new digital currency called Libra next year. (Click here and here). Facebook wraps its announcement in humanitarian gauze – it’s simply providing an effective payment service to the world’s unbanked citizens. As Evgeny Morozov points out, however, Facebook is actually doing two things:

- Preparing to take on China’s social media giants, Tencent and Alibaba, which already combine payments and communications.

- Positioning itself as a “as a rebel force against mediocre bureaucrats and sluggish corporate incumbents”. It’s doing battle against a coalition of lazy, inept, corrupt – untrustworthy – bankers, bureaucrats, and politicians. Morozov suggests that Facebook is activating its populist supporters to keep regulators at bay. More broadly, it’s a “plan to break the global financial system.”

Could Facebook’s Libra actually become a global currency at the expense of the dollar, yen, Euro, and renminbi? Facebook currently has 2.38 billion active users. That number makes even China’s population look small. If a significant portion choose the Libra over existing currencies, then the money we know today could become irrelevant. If a nation’s currency is irrelevant, how relevant is the government?

Given all this, here’s a basic question — whom do you trust more: 1) the American government; or 2) Facebook?

(Note that JPM Coin and Libra are not truly cryptocurrencies, at least not in the original sense of the word. A cryptocurrency has three elements: 1) No central authority, agency, governing body or processor. Clearly J.P. Morgan and Facebook are centralized governing bodies. 2) No physical assets backing the currency. JPM Coin, uses the U.S dollar as its backing asset – it’s a digital currency based on a fiat currency. Facebook says that Libra will be based on physical assets, though it hasn’t quite defined them. 3) Permissionless – you don’t have to ask anyone’s permission to use a cryptocurrency. To use JPM Coin, you need to have an account at J.P. Morgan. To use Libra, you’ll need a Facebook account. Given this, it’s probably best to call JPM Coin and Libra “digital currencies” as opposed to “cryptocurrencies”.)

Innovation & Sociology – Jobs To Be Done

Not to stay warm

Thirty years ago, I was a product manager for a startup company that created high-performance, multiprocessing minicomputers. Powerful, scalable, and based on open standards, they offered exceptional price/performance. In 1988, Electronics magazine gave its Computer of The Year award to the flagship model

As we introduced the system, we described the “ideal” customer: a medium to large organization that used Unix-based systems, and ran large database applications, especially Oracle applications. We trained the sales force, produced some modest direct mail campaigns, and launched.

Then reality set in. In the first three months, we sold about 45 machines to some 30 different organizations. We gathered data about our new customers and looked for correlations that would help us target prospective customers more precisely. We found nothing — no patterns in terms of size, SIC code, geography, application, and so on. The data were almost random.

We were stumped. So, we decided to interview the key decision maker in each account. We created an interview guide and fanned out to visit customers

After our visits, we dug into our findings. Again, we found no useful patterns in the demographic data. Then we started describing the key decision makers. Who were they? Why did they decide on us?

Most of the decision makers were men in their early thirties who had recently been promoted to a position typically described as VP, Data Processing. They replaced an older person who had held the same position for more than ten years. One of our marketers had a flash of insight: “It’s almost like the decision maker is saying, ‘I’m the new sheriff in town. We’re going to do things my way. This is one of my first big decisions … and we’re going to buy a hot new machine from a startup company. I’m going to make my mark.’”

It turned out to be a very accurate description. Nominally, our customers were buying our machines to run large applications. But psychology was perhaps more important. We estimated that roughly 60% of our customers fit the “new sheriff” profile.

We decided to market specifically to new sheriffs. We trawled through organization profiles and identified those that had a new VP of Data Processing. We sent each new sheriff a fairly intense mail campaign coupled with calls by our local sales rep. The campaign succeeded rather well. From the time of the launch, we grew to $300 million in revenue in about two years.

I didn’t know it at the time, but we were practicing an art that today is called, the “jobs to be done theory of innovation.” (Click here for a good introduction). Developed by Clayton Christensen and his colleagues, the basic idea is that demographic information doesn’t reveal why a person chooses to purchase a new product or service. If we misunderstand the job to be done, our innovations will miss the mark.

Our startup company, for instance, positioned around big machines for big databases. We wanted to offer ever bigger, pricier machines. The new sheriff profile, however, changed our thinking. To get in the door, we needed to make it easy for the new sheriff to buy something on his own authority. So, we introduced an entry-level machine priced just below a typical VP signature limit.

Similarly, think about why men buy pajamas. We might think they simply want to stay warm. But men in America typically don’t buy pajamas until they have a daughter who is three years old. Their motivation is not to stay warm but to preserve their modesty. If we misunderstand that, we’ll produce far too many cozy, warm, flannel pajamas that men will never buy.

In my experience, good marketers and salespeople use the jobs-to-be-done method naturally and intuitively. They’re good observers and naturally ask a basic question: why do people buy these products? They dig into the data but, more importantly, they observe how people behave and ask insightful questions. The management guru, Ted Levitt,was a natural at this. He noted that people don’t buy gasoline for their cars. Rather, they buy the right to continue driving.

The jobs-to-be-done theory suggests that the key to innovation is sociology, not technology. Do you want your company to be more innovative? It’s time to add more marketers and salespeople – and maybe a sociologist and anthropologist – to your development team.

My Buddy, The Bitcoin Broker

My buddy, Yancey, is a Bitcoin broker. He’s been arranging deals part-time for several years now. About a year ago, he went full time. He seems to be doing fine.

It’s ironic that the Bitcoin needs a broker. In my opinion, the best thing about Bitcoin, and the underlying blockchain, is the potential to disintermediate transactions. By eliminating middlemen, blockchain systems may deliver two major benefits:

- Reduce the cost of transactions;

- Make transactions easier and faster to complete.

Conceivably, the blockchain can produce a world of frictionless commerce where we no longer need trusted intermediaries. It’s ironic that Yancey serves as an intermediary for a technology that aims to eliminate intermediaries.

This suggests the blockchain has not yet reached its full potential. My question for Yancey: will it ever? I chatted with Yancey for about an hour last week. Here are some of the highlights.

- Bitcoin was an experiment. Nobody expected it to sweep the world. It’s more like a science fair project than a NASA space shot. The surprise is that it works not that it’s imperfect. Don’t judge the viability of blockchain or of digital currencies based solely on the Bitcoin experience.

- Bitcoin’s base software ensures that the system can never produce more than 21 million Bitcoins. People can “mine” the coins through computationally intensive transactions. The more miners participating, the more challenging the transactions become. The world has now mined approximately 17 million Bitcoins; we’re still several years away from the limit. This architecture delivers two additional benefits:

- It’s so difficult to create coins that no one entity can dominate the entire system. Dispersed responsibility and record keeping are the keys to Bitcoin’s security, veracity, and trust.

- When the limit is reached, no more coins can ever be created. Thus the currency can’t be inflated as fiat currencies can. If demand rises and supply can’t respond, the value of each Bitcoin will also rise. (As values rise, we’ll need to subdivide Bitcoins into ever-smaller units for day-to-day use. Today, a satoshi is the smallest available sliver – it’s one-hundredth of one-millionth of a Bitcoin or .00000001 BTC.)

- While Bitcoin has captured the headlines, the blockchain is potentially a much greater disrupter. We can make virtually any information fraud-proof. As I’ve reported before, Peruvian landowners are storing their titles in blockchain databases to prevent land fraud. Sports memorabilia collectors want to create a chain of evidence that proves that this baseball was the one Mark McGwire hit for number 70 on September 8, 1998. Antique and fine art dealers similarly want a tamper-proof record of provenance. Authors, artists, and scientists want to prove that their important discovery or manuscript or painting existed on or before a given date. Before blockchain, we needed trusted intermediaries to verify these facts. With blockchain, perhaps we don’t.

- It’s still the Wild West in crypto/block land but settlers are bringing barbed wire to set up fences. Banks, in particular, sense that they are ripe for disintermediation. Why should customers wait for days for a check to clear – while the bank reaps the float – when we can make instantaneous transfers without a middleman? Banks would prefer to cannibalize themselves than have someone else do it for them. To do so, they need some guardrails but would rather not invite full-bore government regulation. They need to show that they can police themselves. (J.P. Morgan’s announcement of JPM coin– which debuted while I was chatting with Yancey – is a step in this direction.)

- People worry about the use of cryptocurrencies to support terrorism, but some constraints are already in place. These include:

- KYC – Know Your Customer – helps institutions identify “bad actors” throughout their transaction chain.

- AML – Anti-Money Laundering – a set of procedures and regulations that help to identify and stop money laundering.

- CTF – Counter-Terrorist Financing – helps institutions identify, trace, and recover illegally obtained assets.

Additionally, the structure of the blockchain itself can help prevent fraud. What’s stored in the blockchain can’t be changed. A bad actor could conceivably add to the blockchain but such additions are easy to identify and trace.

- Arbitrage by hedge funds is driving much of the trading in Bitcoin (and other digital currencies) today. Hedge funds can lock in a price (for two or three hours) and find a buyer at the same time. The fund buys at the spot price minus one or two percent and immediately sells at the spot price. I asked Yancey how I could play this game. He asked if I had $40 million to get started. Not yet.

- Stablecoins are the next wave. Bitcoin has no assets behind it – its value is simply a question of supply-and-demand. In other words, it’s just like a fiat currency. Stablecoins are based on some asset – like Venezuelan oil or Zimbabwean gold. Stablecoins aim to reduce the wild price fluctuations seen in so many digital currencies. The downside? Someone or some entity has to manage the physical asset. Once again, we have to place our trust in an intermediary.

- The JPM Coin is an interesting variant of a stablecoin. It’s linked to the dollar: one JPM coin = one dollar. So, the coin is based on an asset. But the asset – the dollar – is not based on anything. It’s a fiat currency. It’s not clear if this will help or hinder the adoption of JPM Coin.

- The next wave of competition will come at the platform level. Several different companies have created platforms for creating blockchain systems. It feels like the database wars of the early 80s. Which one (or ones) will dominate? More on that the next time I catch up with Yancey.

Tongue-tied On Valentine’s Day?

Valentine’s cards intrigue me. Suellen and I exchange them every year. Some are sweet. Some are funny. Some are silly. Some are mildly sexy. But really, is there anything new in them? Have we come a long way, baby, or are we just recycling platitudes? And how did people in past centuries address their love, passion, and heartaches? What can we learn from our ancestors?

Valentine’s cards intrigue me. Suellen and I exchange them every year. Some are sweet. Some are funny. Some are silly. Some are mildly sexy. But really, is there anything new in them? Have we come a long way, baby, or are we just recycling platitudes? And how did people in past centuries address their love, passion, and heartaches? What can we learn from our ancestors?

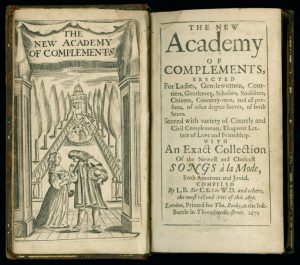

By happy accident, I discovered a partial answer in the Newberry Library in Chicago. The Newberry holds a copy of The New Academy of Complements published in London in the 17th century. The small book – easily tucked in a pocket — is addressed to “both Sexes” and contains a “variety of Courtly and Civil complements” as well as “Eloquent Letters of Love and Friendship … both amorous and jovial.” Happily, the compliments are compiled by “the most refined Wits of the Age.”

What were the best amorous compliments of 17thcentury England? Here are a few of my favorite selections. *

Complemental Expressions towards Men, Leading to The Art of Courtship.

Sir, Your Goodness is as boundless, as my desires to serve you.

Sir, You are so highly generous, that I am altogether senceless.

Sir, You are so noble in all respects that I have learn’d to love, as well as to admire you.

Sir, Your Vertues are so well known, you cannot think I flatter.

Complements towards Ladies, Gentlewomen, Maids, &c.

Madam, When I see you I am in paradice, it is then that my eyes carve me out a feast of Love.

Madam, Your beauty hath so bereav’d me of my fear, that I do account it far more possible to die, than to forget you.

Madam, Since I want merits to equallize your Vertues, I will for ever mourn for my imperfections.

Madam, You are the Queen of Beauties, your vertues give a commanding power to every mortal.

Madam, Had I a hundred hearts I should want room to entertain your love.

I don’t have room to quote many of the gems contained in the book, but here are a few of the categories. Each category provides several models of what to say or write to address the situation. Who knows – you might need one from time to time.

A Gentleman of good Birth, but small Fortune, to a worthy Lady, after she had given a denial.

The Ingratiating Gentleman to his angry Mistriss.

The Lover to his Mistriss, upon his fear of her entertaining a new Servant.

The Jealous Lover to his beloved. The Answer: A Lady to her Jealous Lover.

A crack’t Virgin to her deceitful Friend, who hath forsook her for the love of a Strumpet.

A Lover to his Mistriss, who had lately entertained another Servant to her bosom, and her bed. The Answer: The Lady to her Lover, in defence of her own Innocency.

As you can see, The Academy provides the words to address (and perhaps remedy) most any situation. Is a bald man bothering you? Here’s how to respond:

Sir…while I could be content to keep my Coaches, my Pages, Lackeys, and Maids, I confess I could never endure the society of a bald pate.

I think the Newberry might find an interesting niche market by publishing high quality Valentine’s cards with extracts from The Academy. I know I would buy some. In the meantime, I hope you can find an appropriate quote for whatever your needs are this Valentine’s Day

* The edition held by the Newberry Library was published in 1671. The selections in this article are drawn from the 1669 edition