Serial Thinking

Did he or didn’t he?

What can Serial teach us? How to think.

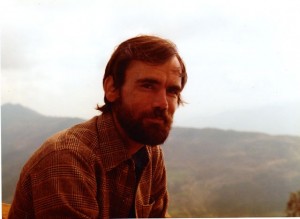

Suellen and I just drove 1,100 miles to visit Grandma for the holidays. Along the way, we listened to the 12 episodes of the podcast, Serial, created by the journalist Sarah Koenig (pictured).

Serial focuses on the murder of Hae-Min Lee, a high school senior who disappeared in Baltimore in January 1999. Hae’s ex-boyfriend, Adnan Syed, was convicted of murder and is now serving a life sentence. Adnan’s trial revolved around: 1) testimony from Jay Wilds, a high school student and small-time dope dealer who admitted to helping dispose of Hae’s body, and ; 2) cell phone records that noted the time and rough location of numerous calls between various students.

Shortly before she disappeared, Hae broke up with Adnan and started dating Don, a slightly older boy who worked at a local mall. When Hae’s body was discovered (under unusual circumstances), both Don and Adnan came under suspicion. Don had a good alibi, however, and Adnan did not. Jay’s testimony pointed at Adnan. Some of the cell phone records supported Jay’s story but others contradicted it. Adnan has consistently maintained his innocence.

Throughout the 12 episodes, Koenig tries to chase down loose ends and unanswered questions. She interviews everyone, including Adnan, multiple times. The case seemed pretty solid at first. Indeed, the jury deliberated only a few hours before returning a guilty verdict. Under Koenig’s relentless scrutiny however, doubts begin to emerge. Could Adnan really have done it? Maybe. Maybe not.

I won’t give away the ending, but Serial is a fascinating look at police investigations and our criminal justice system. For me, it’s also a fascinating way to teach critical thinking. Here are a few of the critical thinking concepts (and biases) that I noted.

Satisficing – we find a solution that suffices in satisfying our needs and cease searching for other solutions (even though better ones might be available). Adnan argues that the police were satisficing when they decided that he was the chief suspect. They stopped looking for other suspects and only gathered evidence that pointed to Adnan. This led to …

Confirmation bias – Adnan notes that the prosecution only presented the cell phone evidence that supported Jay’s version of events. They ignored any cell record that contradicted Jay. That’s a pretty good example of confirmation bias – selecting the evidence based on what you already believe.

Stereotyping – Adnan is an American citizen who is also a Muslim of Pakistani heritage. Many Americans have heard that Muslim men can take multiple wives and that “honor killings” are still practiced in Pakistan. This seems to give Adnan a motive for killing Hae. But is it true or is it just a stereotype?

Projection bias – as we listen to the program, we might say, “Well, if I were going to kill someone, I wouldn’t do it that way. It’s not a smart way to commit murder. So maybe he didn’t do it.” But, then, what is smart about murder? On the other hand, Adnan comes across as smart, articulate, and resigned to his fate. We might project these feelings: “If I were wrongly convicted of murder, I would be angry and bitter. Since Adnan is neither, perhaps he really did do it”. Our projections could go either way. But note that our projections are really about us, not about Adnan. They tell us nothing about what really happened. To get to the truth, we have to ignore how we would do it.

Are there other critical thinking lessons in Serial? Probably. Listen to it and see what you think. I’m not sure I agree with Koenig’s conclusions but I sure love the way she led us there.

Building Your Baloney Detector

Baloney or bologna?

I like to tell wildly improbable stories with a very straight face. I don’t want to embarrass anyone but it’s fun to see how persuasive I can be. Friends know to look to Suellen for verification. With a subtle shift of her head, she lets them know what’s real and what’s not.

My little charades have taught me that many people will believe very unlikely stories. That includes me, even though I think I have a pretty good baloney detector. So how do you tell what’s true and what’s not? Here are some clues.

Provenance — one of the first steps is to assess the information’s source. Did it come from a reliable source? Is the source disinterested – that is, does he or she have no interest in how the issue is resolved? Was the information derived from a study or is it hearsay? Does the source have a hidden agenda?

Assess the information— Next, you need to assess the information itself. What are the assumptions that underlie the information? Are there any logical fallacies? What inferences can you draw? Always remember to ask about what’s left out. What are you not seeing? What’s not being presented? Here’s a good example.

Assess the facts — with the assessment phase, be sure to investigate the facts. Are they really facts? How do you know? Sometimes “facts” are not really factual. Here’s an example.

Definition – as you assess the information, you also need to think about definitions. Definitions are fundamental – if they’re wrong, everything else is called into question. A good definition is objective, observable, and reliable. Here’s a not-so-good definition: “He looked drunk.” Here’s a better one: “His blood alcohol reading was 0.09.” The best definitions are operational – you perform a consistent, observable operation to create the definition.

Interpretation – we now know something about the information – where it comes from, how it’s defined and so on. How much can we interpret from that? Are we building an inductive argument – from specific cases to general conclusions? Or is it a deductive argument – from general principles to specific conclusions?

Causality – causality is part of interpretation and it’s very slippery. If variables A and B behave similarly, we may conclude that A causes B. But it could be a random coincidence. Or perhaps variable C causes both A and B. Or maybe we’ve got it backwards and B causes A. The only way to prove cause-and-effect is through the experimental method. If someone tells you that A causes B but hasn’t run an experiment, you should be suspicious. (For more detail, click here and here).

Replicability – if a study is done once and points to a particular conclusion, that’s good (assuming the definitions are solid, the methodology is sound, etc.) If it’s done multiple times by multiple people in multiple locations, that’s way better. Here’s a scale that will help you sort things out.

Statistics and probability – you don’t need to be a stat wizard to think clearly. But you should understand what statistical significance means. When we study something, we have various ways to compute whether the result is caused by chance or not. These are reported as probabilities. For instance, we might say that we found a difference between treatments A and B and there’s only a 1% probability that the difference was caused by chance. That’s not bad. But notice that we’re not saying that there are big differences between A and B. Indeed, the differences might be quite small. The differences are not “significant” in terms of size but rather in terms of probability.

When you trying to discover whether something is true or not, keep these steps and processes in mind. It’s good to be skeptical. If something sounds too good to be true, … well, that’s a good reason to be doubtful. But don’t be cynical. Sometimes miracles do happen.

Arguments and Sunk Costs

Why would I ever argue with her?

Let’s say that Suellen and I have an argument about something that happened yesterday. And, let’s say that I actually win the argument. (This is highly theoretical).

The Greek philosophers who invented rhetoric classified arguments according to the tenses of the verbs used. Arguments in the past tense are about blame; we’re seeking to identify the guilty party. Arguments in the present tense are about values – we’re debating your values against mine. (These are often known as religious arguments). Arguments in the future tense are about choices and actions; we can decide something and take action on it. (Click here for more detail).

In our hypothetical situation, Suellen and I argue about something in the past. The purpose of the argument is to assign blame. I win the argument, so Suellen must be to blame. She’s at fault.

I win the argument so, bully for me. Since I’ve won, clearly I’m not to blame. I’m not the one at fault. I’m innocent. Maybe I do a little victory dance.

Let’s look at it from Suellen’s perspective. She lost the argument and, therefore, has to accept the blame. How does she feel? Probably not great. She may be annoyed or irritated. Or she might feel humiliated and ashamed. If I try to rub it in, she might get angry or even vengeful.

Now, Suellen is the woman I love … so why would I want her to feel that way? If someone else made her feel annoyed, humiliated, or angry, I would be very upset. I would seek to right the wrong. So why would I do it myself?

Winning an argument with someone I love means that I’ve won on a small scale but lost on a larger scale. I’ve come to realize that arguing in the past tense is useless. Winning one round simply initiates the next round. We can blame each other forever. What’s the point?

In the corporate world, the analogue to arguing in the past tense is known as sunk costs. Any good management textbook will tell you to ignore sunk costs when making a decision. Sunk costs are just that – they’re sunk. You can’t recover them. You can’t redeem them. You can’t do anything with them. Therefore, they should have no influence on the future.

Despite the warnings, we often factor sunk costs into our decisions. We don’t want to lose the money or time that we’ve already invested. And, as Roch Parayre points out in this video, corporations often create perverse incentives that lead us to make bad decisions about sunk costs.

Our decisions are about the future. Sunk costs and arguments about blame are about the past. As we’ve learned over and over again, past performance does not guarantee future results. We can’t change the past; we can change the future. So let’s argue less about the past and more about the future. When it comes to blame or sunk costs, the answer is simple: Don’t cry over spilt milk. Don’t argue about it either.

Mind and Body

Happy Girl

How much does your body affect your brain? A lot more than we might have guessed even just a few years ago. The general concept — known as embodied cognition – holds that the body and the brain are one system, not two. (Sorry, Descartes). What the body is doing affects what the brain is thinking.

I’ve written about embodied cognition before (here and here). Recently, I’ve seen a spate of new stories that extend our understanding. Here’s a summary:

The power pose – want to perform better in an upcoming job interview? Just before the interview, strike a power pose for two minutes. Your testosterone will go up and your cortisol will go down. You’ll be more confident and assertive and knock ’em dead in the interview. Amy Cuddy explains it all in the second most-watched TED video ever.

Willpower, dissension, and glucose – If you run ten miles, you’ll deplete your energy reserves. You may need to relax and refuel before taking up a new physical challenge. Does the same thing happen with willpower? Apparently so. If you resist the temptation to smoke a cigarette, you’ll have less willpower left to resist eating a donut. You can use up willpower just like you use up physical power. Perhaps that’s why you’re more likely to argue with your spouse when your glucose levels are low. If you sip a glass of lemonade, you might just avoid the argument altogether.

Musicians have better memories – experiments at the University of Texas suggest that professional musicians have better short- and long-term memories than the rest of us. For short-term memory (working memory), the musicians are better at both verbal and pictorial recall. For long-term memory, they’re better at pictorial recall. Maybe we should invest more in musical education.

How you walk affects your mood – as the Scientific American points out, “A good mood may put a spring in your step. But the opposite can work too: purposefully putting a spring in your step can improve your mood.” As Science Daily points out, the opposite is also true. If you walk with slumped shoulders and head down, you’ll eventually get grumpy. Your Mom was right: standing up straight actually does affect your mood and performance.

Intuition may just be your body talking to you – when you get nervous, your palms may start to sweat. Your mood is affecting your body, right? Well, maybe it’s the other way round. Your intuition (also known as System 1) senses that something is amiss. It needs to get your (System 2) attention somehow. What’s the best way? How about sweaty palms and a racing heartbeat? They’re simple, effective signaling techniques that are hard to ignore.

The power of a pencil – want to get happy? Hold a pencil in your mouth like the woman in the picture. Your facial muscles act as if they’re smiling. You may consciously realize that you’re not smiling but it doesn’t really matter – your body is doing the thinking for you.

Reality Is A Conspiracy

I want my sweater.

In 1973, when I lived in Ecuador, I survived two nasty accidents within the space of a few days. First, I slid off a glacier and fell roughly 90 feet while climbing in the Andes. I landed in soft snow and wasn’t hurt. A few days later, I flipped over in a Land Rover while driving a mountain road with a friend. The vehicle flipped onto its top, then flipped again and landed on its wheels. My friend and I got out, taped up some broken windows, and drove on.

How could I survive two near-fatal accidents in less than a week? My lucky sweater saved me.

A few days after the flying Land Rover incident, I conducted a mental inventory of everything I had been wearing in the two accidents. The only garment that I had on in both cases was a beat-up old climbing sweater. Clearly, the sweater had protected me from serious harm.

From that point on, I wore the sweater whenever I went climbing. I became quite superstitious about its protective powers. I knew I would be safe as long as it was close to me.

Was my interpretation of reality correct, objective, and reasonable? Most of us would say no. But the pioneering sociologists (and married couple), William and Dorothy Thomas say that it just doesn’t matter. According to the Thomas Theorem, first proposed in the 1920s: “It is not important whether or not the interpretation is correct – if men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.”

The Thomas Theorem can help us understand a range of topics, including conspiracy theories, availability cascades, and self-fulfilling prophecies. We all believe in conspiracy theories of one sort or another. Right-wingers may believe that global warming is a hoax. Left-wingers may believe that big business is a vast conspiracy of the rich against the poor. Whether or not the interpretations are correct, both left- and right-wingers act as if they are real. Their beliefs are real in their consequences.

If we don’t believe in a particular conspiracy theory, it seems completely irrational to us. How could anyone believe that? Anyone who does believe it must be a craven fool. If we know such people, we may try to talk them out of it. We deploy our best logic and most compelling arguments. Typically, we fail to convince them. In fact, we may just cause them to harden their position.

We fail because we misunderstand the nature of conspiracy theories. We think of them as flawed logic (at least, those we disagree with). But in reality, a conspiracy theory is simply a different view of reality. We all have models of reality in our heads. We all want to explain why things are. While all of our models are different, we each believe that our model is accurate. Some of us use theories of history to explain why things are the way they are. Others use religion or Marxism or astrology or conspiracy theories. We all have a belief system that explains everything to our satisfaction.

So how do you change a friend’s belief system? It’s not by arguing logically. Your logic doesn’t apply to his reality. The best approach I’ve found is to ask him to explain how the world works. Don’t ask why he believes it. Ask how it all fits together.

Chances are your friend’s theory of the world doesn’t fit together seamlessly. He probably can’t explain things as thoroughly as he thinks he can. He’s suffering from the illusion of explanatory depth. When he stumbles, he may realize that his theory isn’t coherent and exhaustive. Use questions rather than arguments; let him discover the discrepancies on his own. You won’t convince him otherwise.

Go ahead and give it a try. It may not work but it’s the only technique that has a chance. Just don’t try to take away my sweater.