The United States of Mind

Each cell has its own agenda.

We didn’t really understand the human heart until the mid 17th century, when engineers developed vacuum pumps to move water out of mines. Anatomists realized that such pumps provided an excellent analogy for what the heart does and how it does it. As technology advanced, we used it to learn about our own biology.

In the 20th century, with the advent of the digital computer, we humans reached a similar conclusion-by-analogy: computers show us how our brains work. In the computer, we see elementary logic, various switches flipping on and off, and memory cells that hold information in its most elemental form – binary digits. Perhaps our brains work the same way.

The brain-as-computer analogy has never been perfect, however. The computer, for instance, has a central processing unit (CPU) that manages pretty much everything. The brain doesn’t appear to have an analogous organ. Rather, human thinking seems to be diffuse and decentralized. Indeed, much of our thinking seems to occur outside our brain; the mind is, apparently, much bigger than the brain. Similarly, we can precisely locate a “memory” in a computer. No such luck with a human brain. Memories are elusive and difficult to pinpoint.

Further, the brain is plastic in ways that computers are not. For instance, a good chunk of our brainpower is given over to visual processing. If I go blind, however, my brain can redeploy that processing power to other tasks. The brain can analyze its own limitations and change its functions in ways that computers can’t.

Given the shortcomings of the brain-as-computer analogy, perhaps it’s time to propose a new analogy. Having absorbed a healthy dose of Daniel Dennett (see here and here), I’d like to propose a simple alternative: the brain functions much like the United Sates of America.

That may sound bizarre but let’s go through the reasoning. First, Dennett points out that brain cells, as living organisms, can have their own agendas in ways that silicon cannot. Yes, brain cells may switch on and off as electricity pulses through them, but they could conceivably do other things as well. Perhaps they can plot and plan. Perhaps they can cooperate – or collude, depending on how you look at it. Perhaps they can aim to do things that are in their best interests, as opposed to the interests of the overall organism.

Second, Dennet notes that all biological creatures descended from single-celled organisms. Once upon a time, single-cell organisms were free to do as they pleased. Some chose to associate with similar organisms to form multi-celled organisms. In doing so, cells started to specialize and create communities with much greater potential. However, they also gave up some of their primordial freedom. They worked not just for themselves but also for the organism as a whole. Perhaps our cells have some “memory” of that primordial freedom and some desire to return to it. Perhaps some of our cells just want to go feral.

And how is this like the United States? The original colonies were free to do as they pleased. When they joined together, they gave up some freedom and created a community with much greater potential. We assume that each state works for the good of the union. But each state also has strong incentives to work for its own good, even if doing so undermines the union. Similarly, each state has a “memory” of its primordial freedom and an inchoate desire to return there. Indeed, states’ rights are jealously guarded.

Let’s assume, for a moment, that we have a microscope as big as the solar system. When we examine the United States, we see 50 cells. Each cell seems to be similar in function and process. We might assume that they always function for the good of the whole. But when we look closer, we see that each cell has its own agenda. Some cells (Texas?) may want to go feral to recapture their primordial freedom. Other cells are jockeying for position and advantage. Some are forming alliances and coalitions with like-minded cells to accomplish their aims. Red cells seem to have different values and processes than blue cells.

Could our brains really be as chaotic as the good old USA? It’s possible. If nothing else, such an analogy frees up our thinking. We’re no longer in a silicon straitjacket. We recognize the possibility that living cells may have complex agendas. We start to see possibilities that we were previously blind to. I would write more but I suspect that some of my neurons have just gone feral.

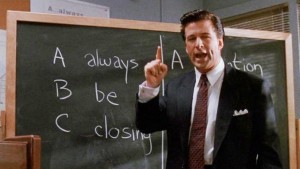

Always Be Conversing

He was so young!

In the 1992 movie, Glengarry Glen Ross, Alec Baldwin played a very hard-nosed sales manager determined to teach a bunch of rookies how to sell. He used intimidation, fear, stress, and money as motivators. He didn’t believe in being nice. He believed in closing.

Baldwin also introduced a term that I’ve heard many times since: Always Be Closing or ABC. The idea is simple – you’re always looking for prospects, qualifying them, moving them through the sales process, and closing them. Then you start over. You’re like a shark – always moving, always eating.

Always Be Closing is associated with pushy, high-pressure sales tactics. You might find them in use at car dealerships or time-share condo conventions. We’re all familiar with them and we all profess to hate them.

Now what about nonprofits? Is Always Be Closing an appropriate technique for raising funds for a nonprofit organization? I don’t think so. For me, nonprofit fundraising is all about relationships. It’s about building for the long run, not closing in the short term.

So I’ve created a new ABC for non-profits: Always Be Conversing. A conversation, of course, has two parts: talking and listening. Always Be Conversing suggests that we’re always ready to talk about our nonprofit organization (NPO) and listen to our constituents’ needs. By conversing with constituents, friends, and our broader network of acquaintances, we build relationships. Over time, those relationships allow us – quite naturally – to ask for donations.

Always Be Conversing also implies that we actively seek out conversations. To create rich conversations, we need to prepare ourselves. Here are some pointers:

- Always have a story – people love stories – they’re easy to understand, relatable, and memorable. When you tell a story, you’re not being a pushy sales person. Rather, you’re building relationships, awareness, and interest. Tip: focus on outputs, not inputs. If your NPO donated a million dollars for scholarships last year, that’s an input. It’s an interesting fact but not a story. On the other hand, if you can describe how your scholarships changed people’s lives, that’s the output of your investment. It’s also a memorable story that most people will be eager to hear.

- Use conversation starters – how does anyone know that you’re passionate about your NPO? How does anyone know that you’re a source of information and assistance? The simplest way is to wear some identification. If you wear a lapel pin or a brooch or a jacket with your NPO’s logo on it, people can identify you and have a conversation. It can happen at random times, so always have a story ready.

- Don’t ask, offer– my NPO is the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. When I wear my NMSS jacket to the grocery store, people frequently ask me about my connection to the Society. Then they often say, “My (wife, cousin, mother, neighbor, etc.) has MS.” I typically respond by saying, “How can I help?” As it happens, NMSS can help in a variety of ways, from insurance advice to exercise programs. But I’m also invoking the reciprocity principle – you’re more persuasive if you offer a favor before requesting a favor.

Over the coming weeks, I’ll write more about fundraising for nonprofits through story telling and relationship building. In the meantime, start telling your stories. You’ll be surprised at the impact you can have.

(My NPO is the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. If you need information about multiple sclerosis or help in dealing with it, just drop me a line. I want to Always Be Conversing).

Self-Herding At Breakfast

Just like Grandma served.

I’ve always believed that breakfast is the most important meal of the day. Why? Because my mother told me so. Why did she believe it? Because her mother told her so. Who told her? Probably Edward Bernays, “the father of public relations.”

Is it true that breakfast is the most important meal of the day? Well, maybe not. If not, I’ve been self-herding for most of my life. I reached a decision (without much thinking) that breakfast was important. My only evidence was my mother’s advice.

Making the decision may have been a mistake. But, c’mon … she was my Mom. The more egregious mistake is that I never doubled back on the decision to see if anything had changed. I made the decision and never thought about it again. I self-herded into a set of fixed behaviors.

I also suffered from the confirmation bias. Researchers published articles from time to time confirming that breakfast is important. These studies confirmed what I already believed. Since the studies didn’t challenge my mental framework, I didn’t bother to check them closely. I just assumed that they were good science.

As it turns out, those studies were based on observations. Researchers observed people’s behavior and noted that people who ate breakfast were also generally healthier and less likely to be obese compared to people who didn’t. Clearly, breakfast is important.

But let’s think about this critically. There are at least three possible relationships between and among the variables:

- Eating breakfast causes people to be healthier – breakfast causes health

- Healthier people eat breakfast more than unhealthy people – health causes breakfast

- Healthier people eat breakfast and also do other things that contribute to good health – hidden variable(s) lead to healthiness and also cause people to eat breakfast.

With observational studies, researchers can’t easily sort out what causes what.

So James Betts and his colleagues did an experimental study – as opposed to an observational study – on the relationship between breakfast and good health. (The original article is here. The popular press has also covered the story including the New York Times, Time magazine, and Outside magazine).

Betts’ research team randomly assigned people to one of two groups. One group had to eat breakfast every day; the other group was not allowed to do any such thing. This isolates the independent variable and allows us to establish causality.

The trial ran for six weeks. The result: nothing. The researchers found no major health or weight differences between the two groups.

But previous research had found a correlation between breakfast and good health. So what caused what? It was probably a cluster of hidden variables. Betts noted, for instance, “…the breakfast group was much more physically active than the fasting group, with significant differences particularly noted during light-intensity activities during the morning.”

So it may not be breakfast that creates healthier outcomes. It may be that breakfast eaters are also more physically active. Activity promotes wellness, not breakfast.

If that’s true, I’ve been self-herding for many years. I didn’t re-check my sources. If I had, I might have discovered that Edward Bernays launched a PR campaign in the 1920s to encourage people to eat a hearty breakfast, with bacon and eggs. Bernays was working for a client – Beech-Nut Packing Company – that sold pork products, including bacon. I suspect the campaign influenced my grandmother who, in turn, influenced my mother who, in turn, influenced me. The moral of the story: check your sources, re-check them periodically, and be suspicious of observational studies. And don’t believe everything that your mother tells you.

(By the way, I recently published two short articles about the effects of chocolate and sex on cognition. Both of these articles were based on observational studies. Caveat emptor).

Mission to Haiti

Future president.

I’m happy to report that the neatest teenager in America lives just down the street from us. Rebecca Kite is 16 years old and she’s bright, cheerful, funny, capable, athletic, and very, very thoughtful. I’m sure she’ll be president of the United States one day. But first she wants to go to Haiti on a mission to help build a school. She’s been working hard in the neighborhood to raise the funds. I told her that, if she could write a good essay, I’d publish it here to promote her cause. She wrote a very good essay. Here it is.

I have a question for you. Do you remember the first time you understood a tragedy? The feeling of your eye brows forcing their way together into a heavy squint, your stomach queasy, and cold goose bumps sprouting up and down your arms?

I can remember the exact day I felt this sensation for the first time. On January 12, 2010, a massive earthquake annihilated Haiti, leaving nearly 220,000 people dead and 300,000 injured. With eyes peering through unfallen tears, I gazed at the television squinting heavily. The screams of pain and sorrow from the wounded and grieving filled the empty air of our basement.

Until this moment, I have never experienced what it is like to be an international citizen. I felt my ears get hot and my cheeks turn red, mourning for people that I have never met, yearning desperately to heal my fellow man but possessing no power to do so. That day, I learned the nature of sympathy and empathy as I cried myself to sleep.

A feeling like this does not just go away after the T.V. turns off. My sadness transformed into determination. I helped organize a school wide bake sale with my 5th grade class that raised $1000+ for the Red Cross in Haiti. I wrote an article about that bake sale that was published on 9news. I donated $50 of my money to the Hope for Haiti Fundraiser. Eventually, there was not much more a ten-year-old could do; my power was limited. I knew I was helping, but I still felt that I had more to give.

When I arrived at Colorado Academy, I found many opportunities to become an international citizen. I could spend my summer in Spain or host a Turkish exchange student.

While these are wonderful opportunities, none of them stood out quite like the “Hope for Haiti Trip in the Spring.” This project aims to build a school for the kids of Nordette, Haiti. According to the brochure, “the new complex will provide cleaner water, better sanitation, and a small medical clinic.”

The project is organized by The Road to Hope, a non-profit started by Rich and Lisa Harris who are parents of students at my school. The organization is dedicated to helping the children of Haiti have a brighter future. The ten-year-old inside me remembers that I yearn to help the people of Haiti in any way I can. Last month, I explained to the application committee how I wish to meet the people, and hear the stories of those I watched cry on television. How I wish to bring support and love to the people who suffered so intensely. How I wish to further strengthen the side of me that is an international citizen, neighbor, and friend.

I have been working for the past month to raise money for this trip. I sent flyers to my neighbors offering my services as a babysitter, dog sitter, house cleaner, and snow-shoveler. I’ve been working Fridays and Saturdays for families around town. I’m working hard and I need to raise the money before March 10th. The trip itself is March 11th to 17th.

I am asking for your consideration in helping me further develop as a citizen of the world. By donating money, you will certainly help me. More importantly, you will help children in Haiti. I would be eternally grateful if you would support my cause. If you’d like to do so, you can go to my secure Go Fund Me, by clicking here.

Thank you so much for reading this. Your support means so much to me.

Conned By The Force

Con artist.

(Warning: spoilers ahead.)

I finally got around to seeing Star Wars: The Force Awakens the other day. It was pretty much what I expected – lots of action, lots of explosions, and a shocking shortage of suggestive double entendres. It’s a very earnest movie.

Here’s what I didn’t expect: I didn’t expect to be conned. But, boy, was I ever. And I fell for it like … well, like a death star falling into a black hole.

As always, it’s a story of good and evil, of course. The vile, evil bad guy is Kylo Ren who dresses like a fashionable Darth Vader. Though we can’t see his face, we know he’s young — the script tells us so several times. Since he’s young, we assume he’s impressionable and, perhaps, redeemable.

And redmption is exactly what we expect when an aging Han Solo confronts him, man-to-man and mano-a-mano. We’re just sure that the wise and wizened Han can save Kylo’s young soul and bring him back to the bright side. (Cue Monty Python: always look on the bright side of life).

And it works! Kylo drops his mask. His eyes fill with tears. His lips tremble. With evident emotion, he hands Han his most terrible weapon, the lightsaber. Han reaches for the weapon and we’re convinced that Kylo is about to be redeemed. Han grasps the saber and we know that angelic music will soon swell to celebrate Kylo’s conversion.

But, no. It doesn’t work out that way. I was conned. More to the point – and with much more devastating effect – Han was conned.

As I look back on the scene, I think: I should have seen that coming from a parsec away. But I didn’t. I wanted to believe. I got conned.

Why was I conned? According to Maria Konnikova, it’s because I wanted to be conned. In her new book, The Confidence Game, Konnikova writes that the con game is “…the oldest story ever told.” Simply put, we’re wired to believe. We want to believe. If we’re unsure about the future, we want someone to tell us a story to reassure us. It doesn’t have to be logical. It simply has to be believable. Since we want desperately to believe, the bar is set pretty low.

The Kylo Ren con also worked on me because I already knew the story. It’s the prodigal son. I’ve always loved the story of the prodigal son, perhaps because I was one. So I was primed. I knew how it’s supposed to end. I half-expected Han to kill a fatted calf and say, My son was lost but now he is found. That’s the way it always happens, doesn’t it? That’s what I want to believe.

Konnikova writes that we ultimately are the enablers of con artists:

“In some ways, confidence artists … have it easy. We’ve done most of the work for them; we want to believe in what they’re telling us. Their genius lies in figuring out what, precisely, it is we want and how they can present themselves as the perfect vehicle for delivering on that desire.”

So how can we protect ourselves against con artists? More on that in future articles. In the meantime, you might consider some traditional Minnesota wisdom: You’re not so special.