When Irrational Behavior Is Rational

We can teach you international finance.

Not long ago, I drove to my doctor’s office for a 10:00 AM appointment. To get there, I drove past the University of Denver and a local elementary school.

The university students were ambling off to their ten o’clock classes. They ambled randomly, crossing the street from different locations and at different angles. Rather then using the cross walks, they often stepped out from behind parked cars. I couldn’t guess where or when they might emerge from hiding and step directly into the path of my car.

The elementary students were also on a break but they were formed up in neat lines. The younger ones held hands in well-organized two-by-two columns. Teachers were in control and the kids only moved when directed by adults. Then they moved only in predictable fashion in predictable directions.

I thought, “Huh … the school kids are much better behaved than the college kids. The college kids should behave like the school kids, not the other way round. The college kids may be learning advanced, abstract concepts but they need to get back to the basics.”

A few days later, I had another think and asked a different question: Which set of kids induced better, safer behavior in me? Clearly, it was the college kids.

Here’s how it works. When I drove past the elementary school, I was aware that school was in session. I drove slowly and paid close attention to my surroundings. At the same time, however, it was clear that the kids were well behaved and under control. I could predict their behavior and I predicted that they would behave safely. I was aware of the situation but not overly concerned.

With the college students, on the other hand, I had no idea what they would do. They were behaving irrationally. Anything could happen. By the elementary school, I was aware. By the university, I was hyper-aware. I drove even more cautiously by the university than by the elementary school.

The college kids influenced my behavior by acting irrationally. As it happens, that’s a key element of game theory – as formulated by John Nash, the brilliant mathematician who was also haunted by mental illness (and who died recently in a traffic accident).

In game theory, if you don’t know what your opponent will do, you may circumscribe your own behavior. I didn’t know what the college students would do, so I drove extra carefully. I ruled out options that I might have considered if the college students were behaving more rationally and predictably.

In other words, acting irrationally is often a perfectly rational thing to do. I’m sure the college students didn’t consciously choose to act irrationally. But a crafty actor might well behave irrationally on purpose to limit her opponent’s options.

In fact, I think this school example perfectly explains the behavior of the finance ministers in the current Greek financial crisis. More on that tomorrow.

McKinsey and The Decision Villains

Just roll the dice.

In their book, Decisive, the Heath brothers write that there are four major villains of decision making.

Narrow framing – we miss alternatives and options because we frame the possibilities narrowly. We don’t see the big picture.

Confirmation bias – we collect and attend to self-serving information that reinforces what we already believe. Conversely, we tend to ignore (or never see) information that contradicts our preconceived notions.

Short-term emotion – we get wrapped up in the dynamics of the moment and make premature commitments.

Overconfidence – we think we have more control over the future than we really do.

A recent article in the McKinsey Quarterly notes that many “bad choices” in business result not just from bad luck but also from “cognitive and behavioral biases”. The authors argue that executives fall prey to their own biases and may not recognize when “debiasing” techniques need to be applied. In other words, executives (just like the rest of us) make faulty assumptions without realizing it.

Though the McKinsey researchers don’t reference the Heath brothers’ book, they focus on two of the four villains: the confirmation bias and overconfidence. They estimate that these two villains are involved in roughly 75 percent of corporate decisions.

The authors quickly summarize a few of the debiasing techniques – premortems, devil’s advocates, scenario planning, war games etc. – and suggest that these are quite appropriate for the big decisions of the corporate world. But what about everyday, bread-and-butter decisions? For these, the authors suggest a quick checklist approach is more appropriate.

The authors provide two checklists, one for each bias. The checklist for confirmation bias asks questions like (slightly modified here):

Have the decision-makers assembled a diverse team?

Have they discussed their proposal with someone who would certainly disagree with it?

Have they considered at least one plausible alternative?

The checklist for overconfidence includes questions like these:

What are the decision’s two most important side effects that might negatively affect its outcome? (This question is asked at three levels of abstraction: 1) inside the company; 2) inside the company’s industry; 3) in the macro-environment).

Answering these questions leads to a matrix that suggests the appropriate course of action. There are four possible outcomes:

Decide – “the process that led to [the] decision appears to have included safeguards against both confirmation bias and overconfidence.”

Reach out – the process has been tested for downside risk but may still be based on overly narrow assumptions. To use the Heath brothers’ terminology, the decision makers should widen their options with techniques like the vanishing option test.

Stress test – the decision process probably overcomes the confirmation bias but may depend on overconfident assumptions. Decision makers need to challenge these assumptions using techniques like premortems and devil’s advocates.

Reconsider – the decision process is open to both the conformation bias and overconfidence. Time to re-boot the process.

The McKinsey article covers much of the same territory covered by the Heath brothers. Still, it provides a handy checklist for recognizing biases and assumptions that often go unnoticed. It helps us bring subconscious biases to conscious attention. In Daniel Kahneman’s terminology, it moves the decision from System 1 to System 2. Now let’s ask the McKinsey researchers to do the same for the two remaining villains: narrow framing and short-term emotion.

Three Decision Philosophies

I’ll use the rational, logical approach for this one.

In my critical thinking classes, students get a good dose of heuristics and biases and how they affect the quality of our decisions. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky popularized the notion that we should look at how people actually make decisions as opposed to how they should make decisions if they were perfectly rational.

Most of our decision-making heuristics (or rules of thumb) work most of the time but when they go wrong, they do so in predictable and consistent ways. For instance, we’re not naturally good at judging risk. We tend to overestimate the risk of vividly scary events and underestimate the risk of humdrum, everyday problems. If we’re aware of these biases, we can account for them in our thinking and, perhaps, correct them.

Finding that our economic decisions are often irrational rather than rational has created a whole new field, generally known as behavioral economics. The field ties together concepts as diverse as the availability bias, the endowment effect, the confirmation bias, overconfidence, and hedonic adaptation to explain how people actually make decisions. Though it’s called economics, the basis is psychology.

So does this mean that traditional, rational, statistical, academic decision-making is dead? Well, not so fast. According Justin Fox’s article in a recent issue of Harvard Business Review, there are at least three philosophies of decision-making and each has its place.

Fox acknowledges that, “The Kahneman-Tversky heuristics-and-biases approach has the upper hand right now, both in academia and in the public mind.” But that doesn’t mean that it’s the only game in town.

The traditional, rational, tree-structured logic of formal decision analysis hasn’t gone away. Created by Ronald Howard, Howard Raiffa, and Ward Edwards, Fox argues that the classic approach is best suited to making “Big decisions with long investment horizons and reliable data [as in] oil, gas, and pharma.” Fox notes that Chevron is a major practitioner of the art and that Nate Silver, famous for accurately predicting the elections of 2012, was using a Bayesian variant of the basic approach.

And what about non-rational heuristics that actually do work well? Let’s say, for instance, that you want to rationally allocate your retirement savings across N different investment options. Investing evenly in each of the N funds is typically just as good as any other approach. Know as the 1/N approach, it’s a simple heuristic that leads to good results. Similarly, in choosing between two options, selecting the one you’re more familiar with usually creates results that are no worse than any other approach – and does so more quickly and at much lower cost.

Fox calls this the “effective heuristics” approach or, more simply, the gut-feel approach. Fox suggests that this is most effective, “In predictable situations with opportunities for learning, [such as] firefighting, flying, and sports.” When you have plenty of practice in a predictable situation, your intuition can serve you well. In fact, I’d suggest that the famous (or infamous) interception at the goal line in this year’s Super Bowl resulted from exactly this kind of thinking.

And where does the heuristics-and-biases model fit best? According to Fox, it helps us to “Design better institutions, warn ourselves away from dumb mistakes, and better understand the priorities of others.”

So, we have three philosophies of decision-making and each has its place in the sun. I like the heuristics-and-biases approach because I like to understand how people actually behave. Having read Fox, though, I’ll be sure to add more on the other two philosophies in upcoming classes.

Maps, Isms, and Assumptions

Looks good to me.

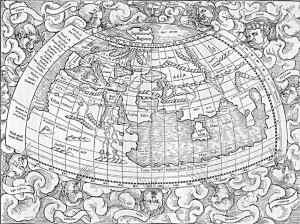

I have a map printed in Germany around 1530 that shows the world as it was seen by second century Greeks. Why would Europeans print a map that was based on sources roughly 15 centuries old? Because Europeans assumed the Greeks knew what they were doing.

Claudius Ptolemy, a Greek mathematician living in Alexandria, wrote a textbook called Geography in 150 AD. The book was so popular and reprinted so frequently – often in Arabic – that Ptolemy became known as the Father of Geography.

My map bears the heading, Le Monde Selons Ptol. or The World According to Ptolemy. It doesn’t include America even though it was printed roughly 40 years after Columbus sailed and roughly 25 years after the Waldeseemüller map became the first map ever to use the word “America”.

When my map was printed, Europe was going through an intellectual revolution. The basic question was: should we believe our traditional sources or should we believe our eyes? Should we copy Greek and Arabic sources or should we observe the world around us? Should we simply accept the Greek version of the world (as we have for so many centuries) or is “progress” something we can realistically aim for?

For centuries, Europeans assumed that the Greeks knew it all. There was no point observing the world and learning new tricks. One could live the best life by bowing to tradition, authority, and faith. This assumption held, in many quarters, until the early 16th century. Then it rapidly changed. You can see it in the maps. By 1570, most maps were in the style of tavola nuova — new maps — based on actual observations. The world had changed and, indeed, the tavolas nuovas look quite a bit like the maps we’re familiar with.

Let’s fast forward to 1900. What did we assume then? Three isms dominated our thinking: Darwinism, Marxism, and Freudianism. Further, we assumed that physics was almost finished – we had only a few final problems to work out and then physics would be complete. We assumed that we were putting the finishing touches on our knowledge of ourselves and the world around us.

But, of course, we weren’t. Today, Darwinism survives (with some enhancements) but Marxism and Freudianism have been largely cast aside. And physics is nowhere near complete. In fact, it seems that the more we learn, the more confused we become.

Even in my lifetime, our assumptions have changed dramatically. We used to believe that economics was rational. Now we understand how irrational our economic decisions are. We once assumed that the bacteria in our guts were just along for the ride. Now we believe they may fundamentally affect our behavior. We used to believe that stress caused ulcers. Now we know it’s a bacteria. Indeed, we seem to have gotten many things backwards.

And what are we assuming to be true today that will be proved wrong tomorrow? In the 16th century, we believed in eternal truths handed down for centuries. I suspect the 21st century won’t be a propitious time for eternal truths. The more we learn, the weirder it will get. Hang on to your hat. That may be all you’ll be able to hang onto.

Are Women Better Spycatchers?

Jeanne Vertefeuille (center) and her team.

Maureen Dowd’s most recent column profiled the sisterhood of analysts at the CIA. It got me wondering: are women better than men at the art of tracking down terrorists and catching spies? Here are three stories that point in that direction.

Story 1: Jeanne Vertefeuille and her team. Vertefeuille started her career at the CIA as a typist in 1954. She then worked her way up the ranks, serving as one of the agency’s first female station chiefs, among many other assignments. Along the way, she became an expert on counterintelligence and the Soviet Union. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, she led a team of five analysts – three women and two men – that unmasked Aldrich Ames, a CIA mole whom the New York Times describes as “one of the most notorious traitors in American history.”

Story 2: “Maya” and her cohorts – in the movie Zero Dark Thirty, Jessica Chastain plays Maya, the CIA analyst who locates Osama bin Laden’s hideout and prompts the mission that killed him. The movie character was fashioned on a real woman in the CIA. According to an article in the Washington Times, the real Maya worked with four other women – including Jennifer Matthews, who was killed in Khost, Afghanistan — to identify and target Al-Qaeda’s leaders. The group became known as the Band of Sisters.

Story 3: The current sisterhood at the CIA. Dowd’s column profiles Gina Bennett, Lyssa Asbill, Sandra Grimes (who worked with Vertefeuille), Kali Caldwell, Jennifer Matthews, and a covert officer named Meredith. Dowd paints a portrait of women who are smart, incredibly dedicated, and nothing at all like Hollywood depictions of female agents. They do, however, have a fondness for the superhero Elastigirl from The Incredibles. As Elastigirl says, “Leave the saving of the world to men? I don’t think so.”

Why might women be better at catching spies than men? When Vertefeuille was asked to help track down a mole, it was assumed that “women had been chosen for the unit because their bosses felt that women would have more patience in combing through records.”

In Dowd’s column, Gina Bennett explains that women think differently than men: “Women don’t think more intuitively than men, but we tend to trust our own gut less. We are not going to put all our money in one basket.”

Is it true that women are more patient than men? Or less likely to be led astray by their own gut feel? Perhaps. But I’m struck by the fact that each of these stories involves teams rather than individuals. A few weeks ago, I wrote an article suggesting that women add value to teams in two key ways:

- They make better decisions about risk, especially under stress. Spycatching is nothing if not stressful.

- Teams that include women are more collaborative, in part, because, women are better able “to read between the lines and understand what someone is really saying.” Understanding what a spy is really saying might well make the difference between success and failure.

In theory, women are better at handling stress, deciding about risk, and understanding what’s really going on. In practice, they’ve caught some of the most notorious spies in our history. Maybe we should just put them in charge.